Mayra Gudiño walked across the central schoolyard at Bridges Academy at Melrose, a public elementary school in East Oakland last fall. It’s a familiar place, where Gudiño has sent all three of her children for their education.

How Greening California Schoolyards Protects Kids and the Climate

But the yard didn’t look much like one, it was closer to an enormous parking lot, surrounded by blue, one-story school buildings.

“I’ve always said Bridges is my second home and the second home of my children,” Gudiño said in Spanish.

But Gudiño said it looks sad. She’d like something far happier for her kids.

“They don’t have green areas, they don’t have shade. Everything is cement, children get hurt very often,” she said.

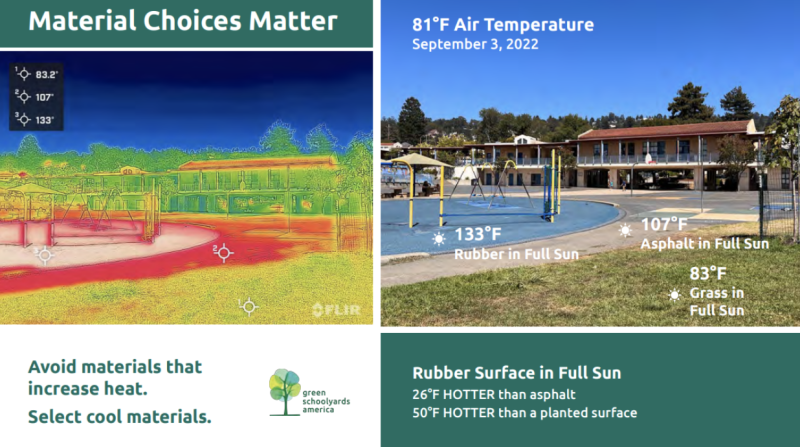

And even on a mild morning, the blacktop beneath Gudiño’s feet was getting warm. Asphalt and other surfaces made from petroleum (asphalt is a byproduct of refining crude oil) heat up far beyond the temperature of the surrounding air, especially in the direct sun. As the world warms, schoolyards like this one are becoming a safety hazard due to extreme heat.

Sharon Danks is the founder and CEO of Green Schoolyards America, a nonprofit that works to transform asphalt playgrounds into ones teeming with nature. She said asphalt-based schoolyards are common: “It’s the standard way our schools have been built: Take out the trees, flatten the site, build your school.”

She and her colleagues are concerned about the effect extreme heat from these schoolyards will have on the young bodies running across them.

Danks has taken many schoolyard heat measurements in her years in this field. “On a 90-degree day when we’ve measured temperatures with our surface thermometers, rubber safety surfaces are 165 degrees and asphalt is a mere 140,” she said. Rubber safety surfaces are spongy materials sometimes made from recycled tires.

Those temperatures can overheat or burn a young body.

Grass, on the other hand, is typically just above air temperature in the sun, and below it in the shade.

Using geographic information system (GIS) mapping, Danks and colleagues at the mapping service GreenInfo Network found that the average California school has just 9% of tree cover. And those trees are typically in places where students are not, like outside the front entrance, or by a parking lot.

All this asphalt can contribute to the urban heat island effect, in which structures like buildings and roads absorb and reemit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes like forests or bodies of water, leading to higher-than-average temperatures in urban areas.

California invests in greening schoolyards

Last year, California earmarked $150 million for green schoolyards. One initiative pushing the work forward is called the “California Schoolyard Forest System,” a collaboration between the California Department of Education, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire), nonprofits Green Schoolyards America and Ten Strands, school districts and county offices of education.

“Our big, green audacious goal is to plant enough trees by 2035 so that when mature, they’ll provide 30% shade cover to child-accessible areas,” said Walter Passmore, a State Urban Forester with CAL FIRE.

Passmore said the money is just a drop in the bucket when you consider the state’s more than 10,000 public schools, roughly 130,000 acres of land, and nearly 6 million students. The program will prioritize schools in communities with high poverty levels, minimal tree cover and hot climates. Passmore hopes the initial funding will be a “down payment,” with more to come in the future.

State legislators also sent a bill to Gov. Gavin Newsom to codify a grant program for school greening projects. Newsom vetoed the bill in September, stating it would put “cost pressure” on the state with an “ongoing commitment not provided for in the budget.”

State lawmakers are working on various bills to accelerate the greening of schoolyards. One bill aims to codify a grant program for school greening projects (a similar bill was vetoed by Gov. Gavin Newsom last year, in which he stated it would put cost pressure on the state with an “ongoing commitment not provided for in the budget”). Another focuses on creating extreme heat plans for schools and includes planting shade trees and gardens. And a third would require various state agencies to build a “master plan for healthy, sustainable, and climate resilient schools.” There are others in the works, too.

Nationally, U.S. Senator Martin Heinrich of New Mexico introduced the Living Schoolyards Act in May, legislation that, if passed, would fund outdoor classrooms and other greening projects through the U.S. Department of Education.

An urban oasis

Just a few miles away from the asphalt schoolyard at Bridges Academy at Melrose is an outdoor space that’s quite the opposite. Oakland Unified School District’s Cesar Chavez campus houses two elementary schools, and nature abounds outside its classrooms.

Kira Maritano is a senior program manager for the Trust for Public Land, a nonprofit that has partnered with the district to pilot a handful of green schoolyards.

Maritano points out some of the 64 new trees on this campus: Catalina ironwoods, southern live oaks, red maples and Chinese evergreen elms. She said they were chosen for a host of reasons, like how fast they grow, how much heat they can tolerate, and how much carbon they can sequester.

“This schoolyard is now built to get cooler and cooler every year as we see the effects of climate change increase,” Maritano said.

The trees shade the yard and building. They cool the air around them through evapotranspiration: water evaporating from their leaves.

There are still sections of asphalt. Maritano explains that they’re needed for the myriad functions a schoolyard serves. But these paved surfaces make up far less of the overall outdoor footprint. A few years ago, the asphalt was fence-to-fence.

Now children swing on ropes attached to logs above wood chips, two girls wander across a “bioswale” — a curving ditch, now dry, which collects stormwater when it rains — and a group of boys play soccer on a grass field. There’s an enormous garden and a fruit tree orchard.

“Giving kids the opportunity to have a tangible relationship with these natural materials is really important,” Maritano said. “A lot of these kids don’t have a chance in their day-to-day life, in their urban environment, to climb on a tree. Just knowing what that feels like starts to break down outdoor equity gaps.”

A green schoolyard is also more permeable than one covered in asphalt or rubber safety tiles.

“This is basically a stormwater sink,” Maritano said, referring to a woodchip-covered play area. “As much as possible, if we can remove asphalt and sink that water back into the earth, we’re benefiting the environment,” and avoiding putting pressure on public utilities like sewer systems, she adds.

Benefits for health, gender equality

Proponents of green schoolyards throw around the word “co-benefits” with regularity. One of the co-benefits of such a yard, beyond cooling a school and even a neighborhood, is better human health.

“Our immune system becomes more robust and stronger against infectious agents when we spend time digging in the dirt, when we have regular exposure to vitamin D from sunlight, and when we engage in physical activity on a regular basis,” said Marcella Raney, of the Office of Well-Being at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

She said for many kids, their schoolyard is one of the only places to exercise and be outside — and, to combat issues like obesity, it’s important that their schoolyard be an inviting place.

Raney has also found differences in how boys and girls use schoolyards: Kids who identify as boys are more active on asphalt schoolyards than kids who identify as girls. That’s because asphalt schoolyards are typically designed for “ball-based” games such as basketball, kickball and dodgeball — larger group sports that are competitive — and, Raney said, these games appeal most to boys.

Green schoolyards appeal to both genders, however.

“Girls are going to be a lot more active on a green schoolyard than they are on an asphalt schoolyard,” Raney said. “When we compare girls versus boys in green spaces, their activity levels are the same.”

Raney has observed that girls favor smaller group activities and want to challenge themselves by climbing, jumping and swinging. A green schoolyard is designed to promote more of these activities.

And, better physical activity for kids tends to mean better school performance.

Barriers to change

For many, green schoolyards are a no-brainer, but there are hurdles to overcome before they’re widely adopted. One such hurdle, according to Cal Poly Pomona landscape architecture professor Claire Latané, is that decision-makers in schools and cities often work in silos, with very specific responsibilities like curriculum design, mental health or maintenance.

But “when we do get people together to have those conversations and really talk about the multiple benefits [of green schoolyards], that conversation changes dramatically, because when thinking about the big picture, everyone wants what’s best for students and the community,” Latané said.

Districts are also hesitant to jump into large projects spearheaded by one “champion,” Latané said, for fear no one will maintain the work when that individual moves on. Schools are understandably risk-averse, and a schoolyard of abandoned trees can become a liability.

Latané said another challenge is that “schools have always been strained for finances in terms of maintenance. And asphalt is seen as a really low-maintenance material,” despite studies showing that over the long term, green schoolyards are actually less expensive than asphalt ones.

LaMonte Douglas was a maintenance project manager for the Los Angeles Unified School District for 35 years. He has since retired. He says that when LA started greening schools, he saw the directive as “yet another thing on the plate to do.”

But when he learned of and saw the benefits of a green schoolyard, he said it became a no-brainer.

He remembers a day he planted a bush at a school site and, immediately, he said, “Some exotic bird came and landed right by that bush. I’ve never seen that type of bird before. And it was almost like the bird was saying, ‘Well, finally, you give me a place to rest.’”

Schoolyard as community space

At Bridges Academy at Melrose in Oakland, Mayra Gudiño lays out a vision for the transformation she wants for her kids’ asphalt schoolyard: trees, green spaces and more color.

It turns out they’ll get it. Through Gudiño and other parents, teacher and administrative activism, the school has received funding to transform their schoolyard: to rip up asphalt and plant trees. They broke ground early this summer.

One condition of their funding is that they keep the schoolyard open for community use on nights and weekends, a boon for their neighborhood without nearby parks.

Gudiño said they deserve it.