What are you doing between midnight and dawn on April 22? Sleeping? There’s a better option: Watch the annual Lyrids meteor shower, and catch up on sleep later.

In the early morning hours of Friday, April 22, especially in the last few hours before dawn, the Lyrids shower will reach its peak of activity, producing as many as 18 meteors per hour under good viewing conditions and a dark sky.

That’s one meteor every three minutes.

How do you watch the Lyrids?

Meteor watching requires minimal planning.

First, find a safe viewing location as far from city lights and overhead obstructions as possible.

Second, plan your viewing for after midnight — best in the last hours before dawn.

And third, bring a snack and a hot beverage, and something comfortable to sit or lie down on.

If you live in or around the cities of the Bay, you may have to travel a bit to find a spot shielded from urban lights. Fortunately, the Bay Area is fringed with decent viewing locations protected by surrounding topography — nothing like you can find far out in the country, but better than downtown San Francisco.

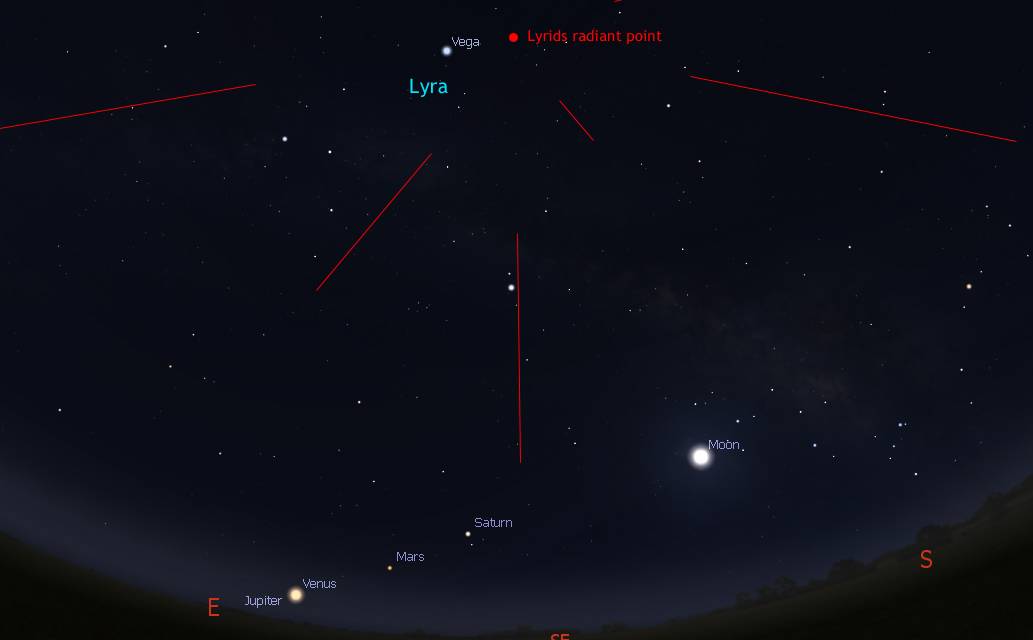

Lyrid meteors streak from a point near the constellation Lyra, their namesake. After midnight, Lyra will be high in the eastern sky, marked by the bright star Vega, one of the luminary members of the Summer Triangle.

Once you find your viewing spot, get comfortable and look toward the east. Though the meteors will radiate from the direction of Lyra, their streaks can appear anywhere, so anchor your sight on Vega, but soften your gaze to see as much of the sky as you can. Now, wait for your reward. Seeing even one shooting star is a thrill. Then, wait for another.

The Lyrids shower also has been known to produce fireballs — exploding meteors — that look like quick, bright bursts of light.

This year, the morning of the Lyrids shower offers a dramatic display from the planets in our solar system. You can spot a lineup of Jupiter, Venus, Mars and Saturn, gradually rising around 4:30 to 5:00 a.m., strung out along the southeastern horizon.

The waning gibbous moon will rise around 1 a.m. and climb higher in the eastern sky for the rest of the night. Moonlight will wash out some of the fainter meteors, but won’t prevent you from seeing the brighter ones.

Where do meteors come from?

A meteor is a tiny bit of space rock or metal incinerated in a flash as it streaks through Earth’s upper atmosphere, at speeds of tens of miles per second. Usually no larger than pebbles, meteors can put on a brilliant light show, sometimes even revealing color — orange, blue or green — depending on composition and temperature.

A meteor shower happens when the Earth moves through a trail of dust left behind by the passage of a comet. As Earth slams into the dust trail at its orbital speed of 18 miles per second, the friction vaporizes the dust grains.

We see meteor showers under morning skies when we’re on the side of the Earth plowing into the comet’s dust trail — inconvenient if you’d like to get a good night’s sleep, but a spectacular show.

The dust trail supplying the Lyrids shower comes from a comet named C/1861 G1, or Thatcher, a “long-period” comet that orbits the sun every 415 years and last passed by the inner solar system more than 160 years ago. Even so, the dust left behind in its wake persists, and every year when Earth passes through it, we can enjoy the Lyrids shower.