Lessons From Experience

He knows what it’s like to escape a wildfire. In 1991, the Oakland Hills fire consumed his neighborhood. Vehicles jammed the roads, so a policeman loaded Matis and his son into another car.

“This incredibly brave woman drove on a twisty road,” he recalled. “She couldn’t see through the flames. And then she drove us to safety.”

Some of his neighbors died trying to escape. Matis’ neighborhood is more fire aware now and the power lines are buried underground. But the people there are not immune from PG&E’s blackouts or from the frustration they cause.

“I’ve talked to PG&E in the past, and I realized they didn’t know what they’re talking about,” Matis said.

The utility would disagree, but other companies see an opportunity in that resentment.

“We’ve had a very big uptick,” said Anne Hoskins, chief policy officer at Sunrun, which sells solar and battery systems. The company saw 15 times more web traffic to its battery pages than usual during the most recent outages. “We have a better way than relying on this over-century-old system that has to take power from far distances to serve communities and people.”

Hoskins said home batteries aren’t just for emergencies. Homeowners can use them every day to store solar power for use when the sun goes down. Other solutions, like portable gas generators, are a temporary measure.

“They’re loud,” Hoskins said. “They’re dirty. And that also contributes to the problem, in our view, that we’re facing, which is climate change.”

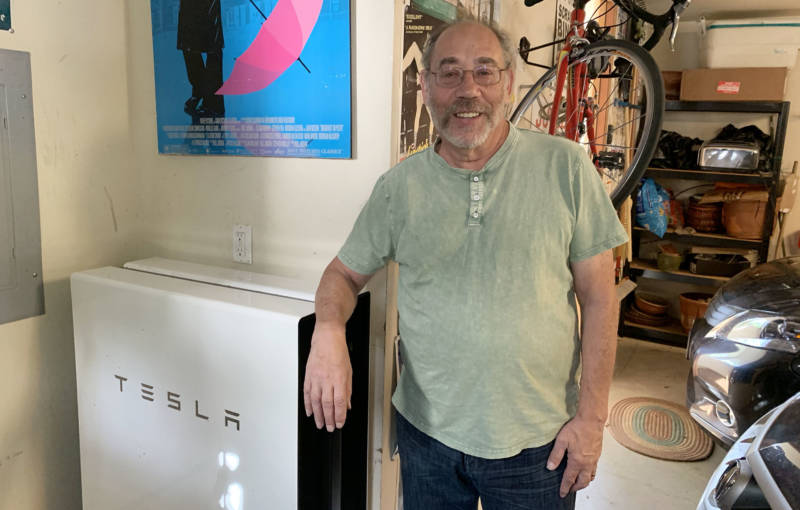

Still, batteries are expensive. Telsa’s Powerwalls, the kind Howard Matis has in his garage, cost around $6,500 each, plus thousands more in installation. CEO Elon Musk recently tweeted that the company was knocking $1,000 off the price of their systems for Californians affected by the outages.

A 30% federal tax credit for solar and battery systems helps reduce the cost. So does California’s Self-Generation Incentive Program, which provides rebates in the thousands of dollars. The California Public Utilities Commission recently carved out $100 million in rebates for low-income households or communities in high fire-risk areas.

Companies like Sunrun also offer leasing options with little money down for home batteries . That adds about $40 a month to a solar lease. But potentially, wealthier Californian homeowners could buy their way out of blackouts, leaving everyone else feeling the brunt.

Sharing the Benefits

“So what you want to do is get ahead of that and figure out, okay, how can we build a system so all those investments that people are making can bring a benefit to the grid as a whole?” Hoskins said.

She added that’s possible with “virtual power plants.” In one project planned by East Bay Community Energy in West Oakland, 500 low-income households will get solar and batteries. During times of high demand, those systems will feed power back onto the grid for everyone to use, almost like a traditional power plant.

The idea is that locally produced power reduces the need for big transmission lines to bring it in from far away.

“There’s definitely some truth to that, but there’s also some real cost to trying to operate smaller grids independently,” said Severin Borenstein, an energy economist at UC Berkeley.

California utilities could spend billions on these microgrids, he says, but they’ll also need to spend billions on improving the existing grid to prevent fires.

“When we make all these investments, if we load it all into electricity rates, we’re going to have even higher electricity rates,” he said.

Higher PG&E rates could encourage more Californians to install solar and batteries to avoid the rising costs. But when households make their own electricity, they buy less from PG&E, so the utility gets less revenue for grid improvements.

“What I have been arguing is that we really need to take some of these programs and take them off of electricity bills and put them into the state budget,” Borentsein said.

Either way, PG&E’s blackouts and ongoing bankruptcy could add urgency to these conversations, as California looks for ways to create a safer and more reliable grid.