This particular California winter has unfolded in good news/bad news fashion. Courtesy of a string of recurring atmospheric rivers, potent storms have caused flooding, power outages and canceled flights. But they have also — by at least one key measure — lifted the state completely out of drought.

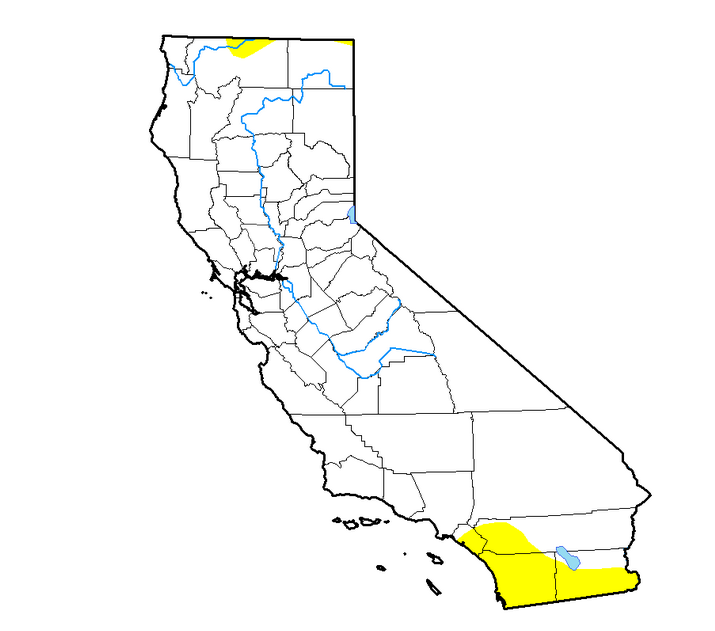

The weekly map released by the U.S. Drought Monitor on Mar. 14 shows no remaining vestiges of California in moderate-or-more severe levels of drought. Less than 7 percent of the state remains “abnormally dry” (yellow areas).

It’s worth noting that while the Drought Monitor, produced jointly by the National Drought Mitigation Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, is one measure of drought conditions, it’s a fairly comprehensive one. Authors take a broad array of factors into account, including groundwater conditions, where data is available.

“We primarily use groundwater data from the USGS; however, data is sparsely distributed across the state,” said David Simeral, one of 12 scientists who take turns assessing conditions for the U.S. Drought Monitor.

More well data is available for areas in Southern California than in Northern California, Simeral says.

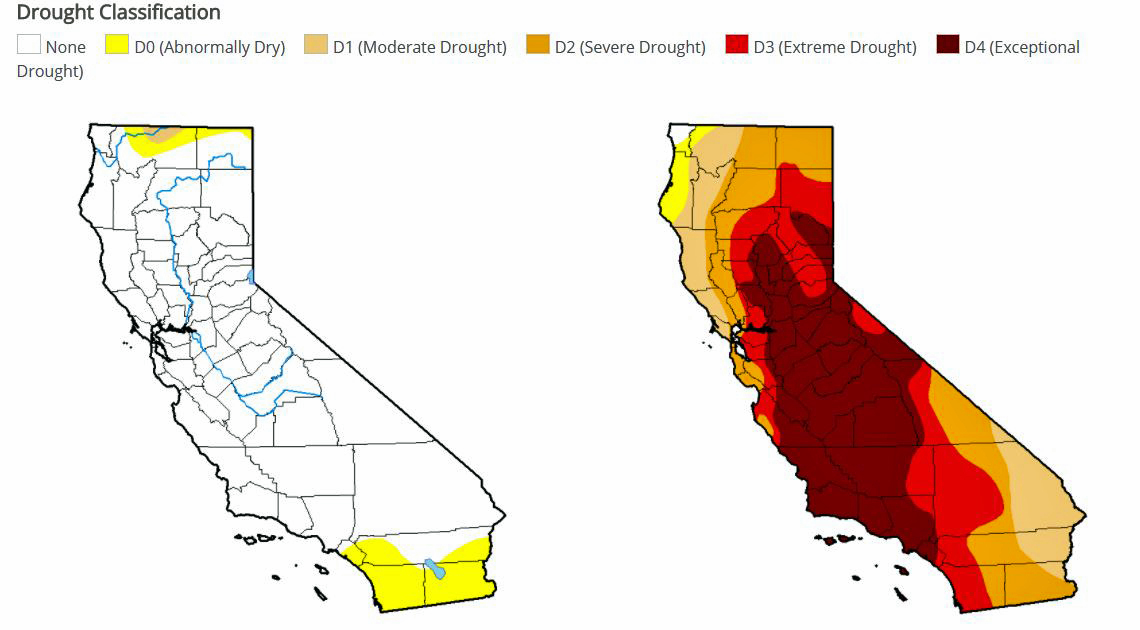

On the left, below, you can see the map released last week by the U.S. Drought Monitor, which is almost completely devoid of colors indicating various levels of parchedness. On the right is the same map from three years ago, bleeding brick-red and showing nearly 40 percent of the state in the most advanced stage of drought.

KQED Science Managing Editor Paul Rogers recently wrote about the state’s stunning water comeback for the San Jose Mercury News, where he reports on science and the environment. Here are some key points from Rogers about current water conditions in California, taken from an interview with KQED’s Brian Watt (numbers reflect the Drought Monitor issued on Mar. 5.)

People were worried at one point about another drought developing. How about now?

After a dry winter last year and a dry December this year, people were starting to worry that the kind of drought conditions we saw between 2012 and 2016 might be coming back. But then it started raining like crazy, particularly in February and through early March, and those rains have really washed away fears of a returning drought. The new report showed that less than 1 percent of California, a tiny sliver up near Oregon, is still in a drought, and it’s classified as “moderate.” So our reservoirs are full, our rivers are full, and things are looking good in terms of the state’s water supply.