As we try to learn more about earthquakes and the geologic forces that create them, we can look in two directions—to the present and to the past. Earthquakes that happen today are well recorded by seismometers, but we have to wait for them. In the meantime, we can cover more time by searching the past. A good recent example is a study mapping a San Andreas Fault earthquake that happened in 1838, long before we had seismometers.

The paper in the February Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, written by Ashley Streig and Ray Weldon of the University of Oregon and Tim Dawson of the California Geological Survey, described some of the painstaking work needed to document earthquakes in the “pre-instrumental period.” It combines written information from dusty archives and geological information from mucky ground.

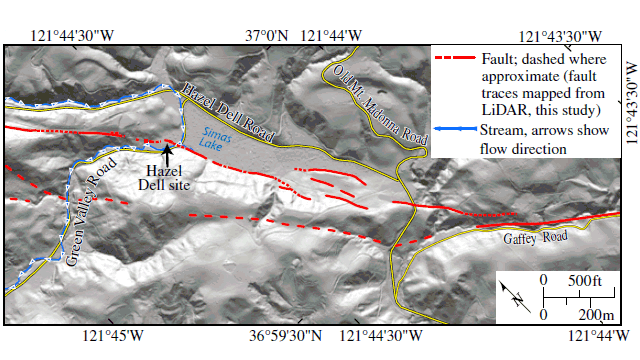

Earthquakes last only moments; despite the destruction they can cause, they don’t leave many lasting traces. Broken buildings are usually cleared away and rebuilt; toppled trees rot away; landslides don’t stand out from those that happen every wet season. This is especially true in the deep woods of the Santa Cruz Mountains, where the San Andreas Fault runs through thinly settled country. But Streig’s team found a little stream valley along the fault’s trace at a locality called Hazel Dell, near the small town of Corralitos north of Watsonville. Here they did a trenching study and documented three large earthquakes—more precisely, three instances of movement on the fault—during the last two centuries.

Trenching is a kind of dissection of the ground. The photos below are from a trenching exercise that I witnessed a few years ago. Here are the steps. First, very carefully map the traces of the fault and pick a spot to dig a trench across the fault, using a backhoe. Insert steel braces in the trench to hold the walls safely up. Next, take hand tools and carefully scrape both walls of the whole trench to best display the layers under the ground. Set up a precise grid of white string and start mapping whatever you can discern.

Mark the boundaries of whatever you see—color changes, different textures, offsets and discontinuities—using a trowel or twig. Mark bits of wood or charcoal that could be dated by radiocarbon.

Lay clear plastic over the trench wall and transfer onto it everything you’ve marked. Add notes. Photograph everything in good light. Print the photos and start pasting them together.

Keep pasting the photos until a complete mosaic is assembled. Roll up the plastic sheets and photomosaics, pack up the samples, pull out the braces and refill the trench.

Take everything back to the lab, assemble it into a database, run tests on the samples, and scratch your head and stare at everything for a long time. It’s an incredible amount of work, but trenching is the only way to pin down prehistoric and pre-instrumental earthquakes. Not every trench pays off, either.