A large team of Antarctic researchers has published instructions for locating the oldest available samples of the ancient atmosphere. If their thinking is correct, we ought to be able to retrieve air from Antarctica’s ice sheets that’s almost twice as old as what we have today.

Ancient ice is a crucially important source of information about global climates of the past. Although the ice itself is a valuable record of regional conditions, the real prize is the air bubbles preserved in it. Because the gases in the atmosphere are so well mixed by winds and weather, even a tiny sample is a faithful record of the whole world. Ice is the gold standard for researching ancient atmospheres. Today’s longest ice cores have given us a record that goes back about 800,000 years. The new paper, published this month in the open-access journal Climate of the Past, raises the possibility of ice as old as 1.5 million years and outlines how to locate it.

We have evidence of ancient climates from other sources: sediment layers on the seafloor preserve microscopic fossils, for instance. These can tell us something about ocean temperatures at different depths in the sea. Those sediment layers pile up essentially forever, too, much longer than ice lasts. But that evidence is always indirect.

Ice is best, but it is geologically perishable. Ice begins to flow as it reaches a thickness of a hundred meters or so. Even on a dead level, it spreads sideways, stretching its annual layers thinner and thinner. At greater thicknesses, ice sheets start to melt at the bottom because of geothermal heat from the Earth’s crust beneath. The oldest possible ice must lie in places with a delicate balance between accumulation and destruction, and that’s what the paper’s authors, led by Hubertus Fischer of the University of Bern, set out to calculate.

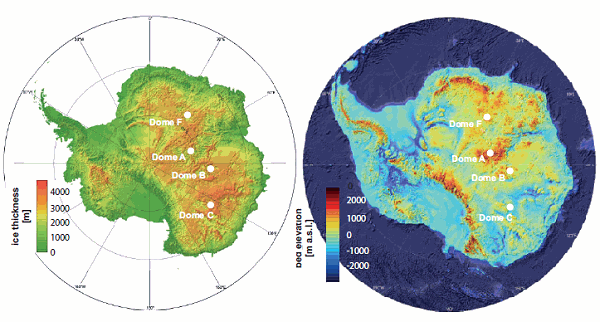

Fischer’s team already knew that sites where Antarctic ice is piled on a high bedrock plateau are best for minimizing flow of all kinds. These are known as domes. The 800,000-year ice core was drilled on Antarctica’s Dome C. But the team showed that Dome C’s very thick ice makes the bottom melt faster than a dome with thinner ice would, limiting the age of its ice. A dome with thinner ice might actually have a longer record. To help their search for older ice the scientists used the latest “hugely improved data set” showing Antarctica’s ice thickness, made using high-powered radar, which easily penetrates ice. Subtracting the ice thickness from the ice surface yielded the best map yet of Antarctica’s hidden bedrock surface.

The sweet spot would be a dome site where the ice is no more than 2.5 kilometers thick. The oldest decent ice would lie about 100 meters above bedrock, because ice flow smears and disrupts the bottom layers. The best sites should also not be windy, to avoid scouring of the ice and “wind glazing” (whereas such “blue ice” regions are superb for hunting meteorites in Antarctica). Fischer’s team ran their maps through their model to yield a map of likely prospects.

Domes A, C, and F look the most promising, but the details matter—there are buried mountain ranges and deep valleys, where the lowest ice would be roiled to uselessness. There is also the unknown degree of geothermal heating underneath different sites. When the search gets serious, detailed radar studies would pick out internal details of the ice. Fischer’s team recommends a strategy of drilling a lot of rapid, shallow holes before launching an expensive coring mission.