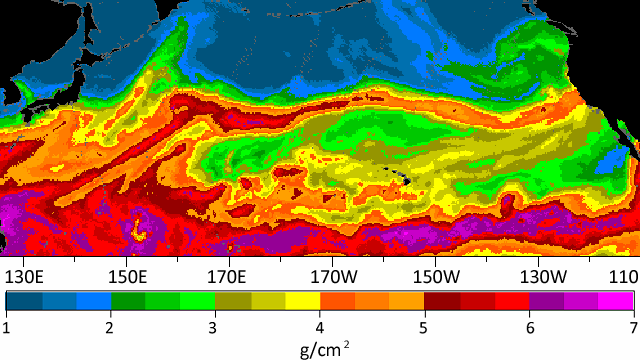

Atmospheric rivers are a 21st-century weather threat that first got their name in 1998, after satellites capable of measuring water vapor in the air began producing images like this one. It shows the chronically humid tropical ocean at the bottom, and long, thin streamers of water vapor threading away from the tropics. It was soon estimated that these streamers—atmospheric rivers or ARs—are responsible for essentially all of the moisture transported out of the tropics.

The basic connection between ARs and major precipitation events was obvious. In California, our 20th-century name for these is the Pineapple Express: a huge influx of warm, water-heavy air from the tropical Pacific that overfills the rivers and piles snow on the mountains. Smaller ARs may not cause major floods, but they can bump up river flows by 10 times in a day or two. They deliver to California about one-third of its total water. Clearly ARs are important research topics for both scientific and practical reasons. How do they interact with El Niño/La Niña cycles? How will climate change affect them? How can we better protect ourselves from them?

America has just finished going through Hurricane Sandy. Hurricanes are important events, but ARs affect both coasts. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's AR site points to the notorious "Snowmageddon" blizzard of February 2010 as an East Coast example, when a river of Pacific moisture crossed Central America and the Caribbean before drenching the Atlantic states.

Norway got a large AR in the late summer of 2005, and many others are sure to be found in the global weather records. But California seems to be the current champion, maybe because the data is better here. Between 1997 and 2006 there were 42 AR events touching California, of which seven caused major flooding of the type requiring evacuations and triggering large-scale power outages.