While nearly all eyes are focused on Mars, two astophysicists at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center have been quietly staring at the sun instead.

Back in 2010, NASA debuted the Living With a Star program by launching the Solar Dynamics Observatory, or SDO, a "sun-pointing semi-autonomous spacecraft." SDO sends data back to earth at a continuous 130 megabits per second, seven days a week, twenty-four hours a day. Scientists Nicholeen Viall and James Klimchuk have used some of this mass of information to create solar images worthy of an art gallery.

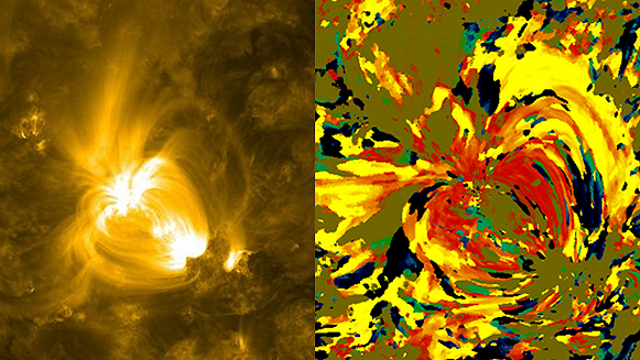

These beautiful pictures, which NASA writer Karen C. Fox calls "reminiscent of Van Gogh," are not only fit to hang on your living room wall, but represent a critical step in solving a major puzzle of heliophysics (that's my favorite new word, by the way): why is the sun's corona so hot?

As you may remember from childhood singalongs, "The sun is a mass of incandescent gas / a gigantic nuclear furnace / where hydrogen is built into helium / at temperatures of millions of degrees." (Fun fact: though most of my contemporaries know that song from the They Might Be Giants cover, I know it from the original 1959 album Space Songs.)

But the surface of the sun is actually only 6000 degrees Kelvin, while the corona (the sun's outer atmosphere) climbs well above a million. How does it get so hot?