Intel makes a lot of computer chips and a lot of money and like many businesses that rely heavily on cutting-edge research, they recognize the need to invest in the future. Since 1997, Intel has sponsored an International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) for high school students.

It's not the kind of science fair with vinegar volcanos. ISEF student projects can be just as esoteric as Nobel laureates' research (indeed, seven ISEF alumni have won Nobel prizes). It can feel like you need several PhDs just to understand the project abstracts. But this year, those of ISEF's student scientists lucky enough to be paired with professional artists will see their research translated into compelling and accessible posters for the public.

NPR covered some of these posters in "When Art Meets Science, You'll Get the Picture," but the Intel SciArt series is so chock-full of goodness that I couldn't resist exploring further.

"This illustration depicts the finding of a 'needle in a haystack,' as it were, in reference to the Apadora algorithmic processes to find the correct data in the glut of information that is twitter feeds," says Portland-based artist Adam Garcia. He designed the poster to communicate the research of Nicholas Schiefer, a Canadian student whose "microsearch" algorithm won the Intel Foundation Young Scientist Award. The algorithm, named Apodora after a New Guinean python, follows connections between words to infer relatedness (for example, "cat" and "kitten" are more closely related than "cat" and "particle") then uses the information to improve searches in short bits of text like tweets and headlines.

Garcia's poster offers a beautiful concrete metaphor (and unfortunately a misspelling) of an abstract computer algorithm. Other SciArt posters illuminate more concrete science, and find their challenge in deciding which aspect of the work to highlight.

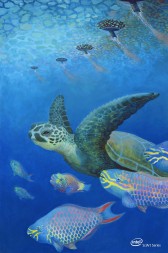

In "Clean Water," Los Angeles artist Alexa Dunham chose to focus on the potential outcome of applying the discovery, rather than the discovery itself. Her scientists were a group of Japanese students who stumbled across a technique for collecting spilled oil while studying the hunting technique of the archerfish.