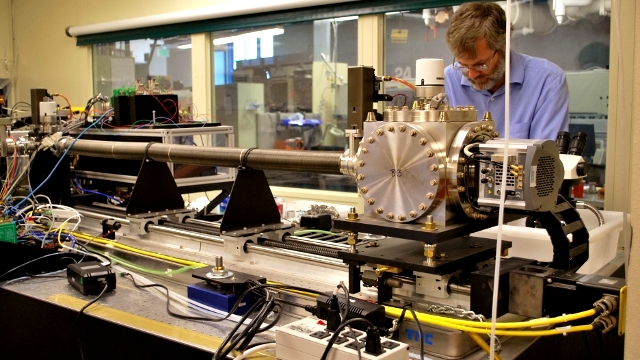

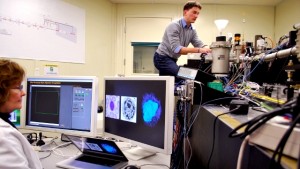

Mark LeGros, who spent three years building the world's first x-ray microscope dedicated to cell biology, greeted me at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) with a welcoming handshake and an accent which clips along in a musical pace, an acoustic stamp of his New Zealand roots.

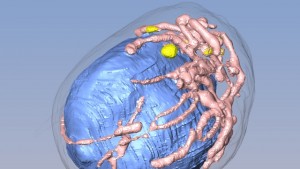

I spent an hour in April talking with him about the challenges and rewards of creating a device which can capture a truer, more accurate representation of a whole cell and its organelles, or the tiny but essential cellular structures such as a cell's nucleus and its mitochondria, the latter of which supply a cell with energy.

I asked him to take me back to that moment when he and the diverse team of researchers, including biologists, physicists, chemists and computer scientists, who comprise the National Center of X-ray Tomography at LBNL powered up the microscope and waited anxiously for the first images to arrive of a yeast cell, the first biological specimen they selected for imaging.

"I wasn’t sure exactly just how well this was gonna work out. But it turned out that it was beautiful...and everybody associated with the project was stunned with the degree of detail that it revealed about the internal structure of a cell and the chromatin, which is the genetic material of the cell," he said.

It's important to note that this x-ray microscope by no means makes obsolete other imaging modalities such as light microscopy and electron microscopy. For one thing, the cell sample is frozen to hold the structures in place and protect them from the x-rays which have much greater penetrating power than visible light because x-rays have much shorter wavelengths than light rays. So it can't capture dynamic activity of cells moving in real-time, which a confocal microscope can capture. Also, while the resolution possible with the x-ray microscope is five times greater than a light microscope, an electron microscope, which uses electrons to penetrate ultra-thin sections of cells, provides better resolution than the x-ray microscope.

Nonetheless, what this x-ray microscope offers, unlike an electron microscope, is the ability to see a whole cell in its native state, with the only preparation being the freezing of the cell sample. Its worth noting that many of the images of cells people recall from their high school biology days were taken with electron microscopes which required the cells to be dehydrated and stained with heavy metals to bind the electrons to the cell and generate an image. Since a cell is 70% water, dehydration and staining can degrade delicate cellular structures and make it difficult to accurately visualize them.