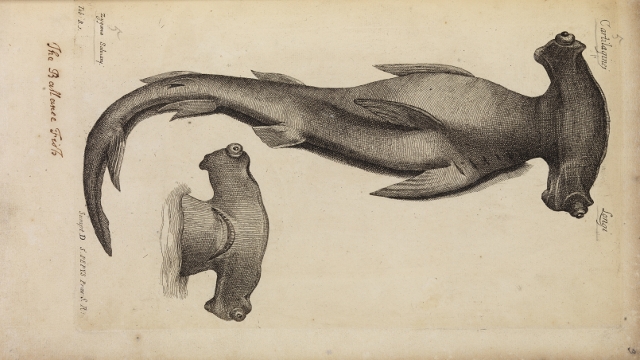

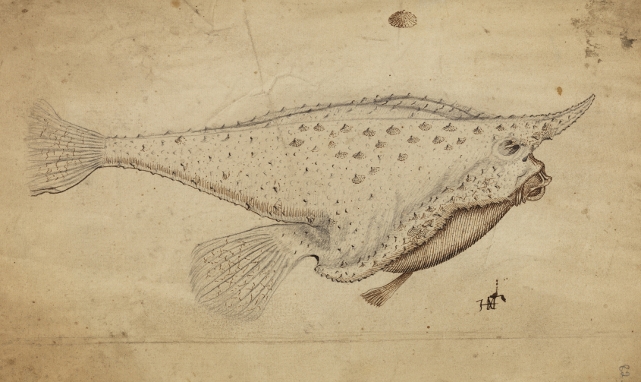

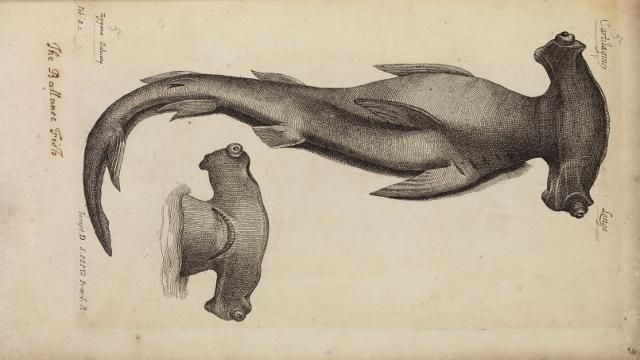

A hammerhead shark's baleful stare. A longnose batfish's fierce armor and delicate fins. These masterpieces of expression and scientific detail fill the pages of the world's first ichthyology book, De Historia Piscium, published in 1686 by the Royal Society.

Then as now, it was a pricey proposition to produce an image-heavy book. Historia Piscium cleaned out the Royal Society's coffers so thoroughly that the academy couldn't afford to publish Isaac Newton's Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica--nowadays usually referred to as the Principia and considered the foundation of modern physics.

Luckily for modern physics, the Society's clerk Edmond Halley (later of Comet fame) took a fancy to Newton's treatise and financed its publication himself the following year. No doubt appreciative of his service but unable even to pay his salary, the Royal Society offered to pay Halley in copies of Historia Piscium. (So says Bill Bryson.)

It could be tempting to call the experience, as indeed the Royal Society recently did, a "fishy blunder." Certainly it was financially untenable. But although it doesn't share the modern fame of the Principia, Historia Piscium was a groundbreaking work in its own way.

This was fifty years before Linnaeus' Systema Naturae and more than a hundred and fifty before Darwin's Origin of Species. Without the former's organized system of naming animals or the latter's understanding of relationships between them, author-illustrators Francis Willughby and John Ray still managed to produce careful scientific classification and beautifully detailed illustrations of hundreds of fish species. Historia Piscium remained the definitive work on fish biology for over a hundred years.