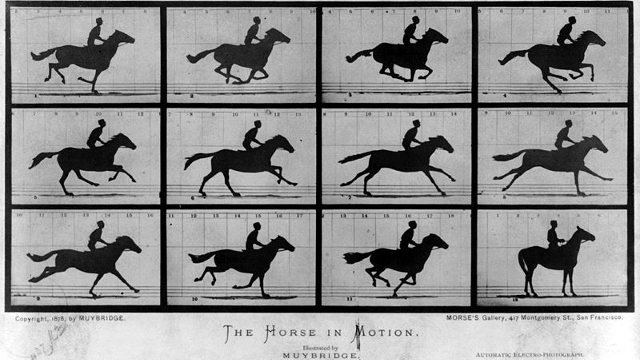

Monday was the 182nd birthday of Eadward Muybridge, the moving picture pioneer who first answered the question: do all four feet of a galloping horse leave the ground at once?

Muybridge took his famous horse photographs at the Palo Alto Stock Farm, 14 years before it would become Stanford University. Leland Stanford himself, former California governor and race horse owner, had hired the photographer simply to satisfy his curiosity.

But Muybridge had bigger ideas. He created a device called the zoopraxiscope that projected still images from a spinning disc, creating the illusion of motion. (I'm disappointed that history nixed "zoopraxiscope" in favor of "film projector." BORING.) In 1880, Muybridge presented a public screening of his running horse that was probably the world's first movie, though no one called it that at the time.

However, Muybridge's remarkable contributions to film often overshadow his instrumental role in kickstarting the science of biomechanics. He was fascinated with locomotion, and moved on from horses to study a variety of other animals. The field has blossomed since Muybridge's time: modern high-speed cameras can record hummingbird wings and the world's fastest flower (!). I've even used high-speed video combined with a microscope to study the locomotion of baby squid--which brings us to the next curious character in this tale.

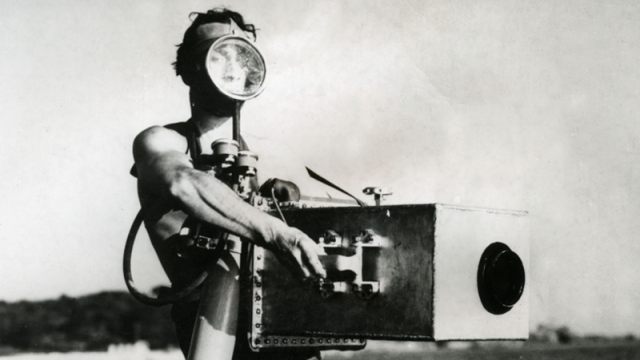

As anyone who's seen Hugo knows, the French picked up where Muybridge left off and began to make all kinds of marvelous films. You may have heard of the Lumière brothers (The Arrival of a Train at La Ciolat Station, 1885) and Georges Méliès (A Trip to the Moon, 1902), but what about Jean Painlevé?

Painlevé was a French artist and scientist who loved marine animals and film. The first underwater camera housing, which he helped develop, let him combine his passions. His early films (with names like The Stickleback's Egg and The Devilfish) amazed audiences from the 1920's through today with their meticulous scientific detail. Yet Painlevé's interest in a surrealist aesthetic brought anthropomorphism and metaphor into what might otherwise have been simple educational movies.