In “The American Practice of Medicine,” Connecticut-born Wooster Beach writes that peppermint is “agreeable and penetrating, slightly bitter, followed by a sensation of cold in the mouth” and good for settling the stomach.

You can also look up ways to fight flatulence, hysteria, dropsy (inflammation), piles (hemorrhoids) and cardialgia (heartburn).

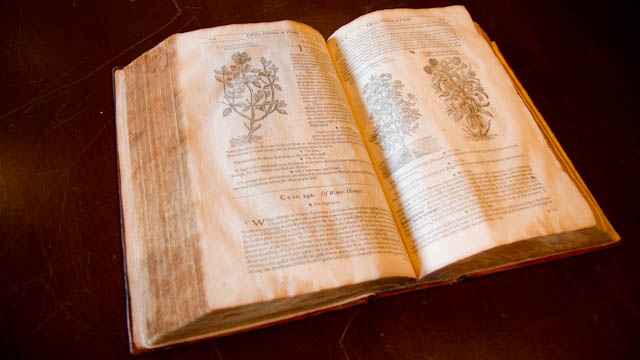

One of the oldest texts is a 1633 edition of John Gerard's “Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes.” The English herbalist includes detailed line drawings and warnings against the most poisonous plants.

“For them to say something will kill you immediately, probably means it was pretty harsh,” Peeples said. “Given the amount of enemas and purgatives these people were taking. It had to be really bad. We like to call it “heroic medicine,” that idea that the physician will go to any means to cure you, even if meant killing you.”

Most of the books were part of the hospital's active lending library and are amazingly preserved, especially Mark Catesby's “Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands.” It's a picture book of plants and insects illustrated on deeply saturated color plates – and lovely for art’s sake alone.

Wendy Grube is a nurse practitioner and registered herbalist who teaches a course on alternative therapies at the University of Pennsylvania. She collects her own historical volumes on plant medicine and has done research in the Pennsylvania Hospital archives.

“Flower to Pharmacy” includes some of the first “materia medica” produced for an American audience, and Grube says the meticulous anthologies are fascinating for modern day herbalists.

Early colonial doctors had a very different conception of disease and hadn’t discovered viruses or bacteria, but Grube says that didn’t keep them from hitting on the true medicinal value of plants.

Sage, for instance, is antimicrobial and thyme has anti-viral properties.

Physicians made connections from careful observation over time, Grube says. Doctors likely didn’t understand that an herb was killing off microbes, but it was clear that certain plants helped for cold and cough, she said.

“Flower to Pharmacy” collects the texts used by white, male physicians at Pennsylvania Hospital in the 1700s, but Grube says their records include knowledge learned from Native Americans and traced back to ancient Egypt and Greece.

Curator Stacey Peeples said some of the information in the library collection was surely common knowledge among Colonial women who kept their own recipe books.

“Today if you have a headache, you don't run to the hospital,” Peeples said. “The first thing do, is you take an aspirin. It was similar at that time. The woman was entrusted with the care of the family.”

“Why did these traditions happen? They happened because they were effective. I don't think people really waste their time on things that aren't effective,” Grube said.