Earthquake engineering is a discipline that uses a wide range of techniques: There's forensics, for diagnosing collapsed structures. There's 3D dynamic computer simulations, to test building designs in silico. And there's the mechanical joy of giving things a good hard shake. The last part, clearly, is the sugar that draws the news flies. It certainly brings out the little boy in me.

There are all kinds of ways to subject things to seismic-style shaking. At a scientific meeting not long ago I watched a contest that took student-designed model buildings and put them on a shake table the size of a large microwave oven. A shake table is outfitted with actuators—pistons pushing in all directions—that "play" a seismogram, the record of an actual earthquake. The students and judges were serious, but somehow gleeful too, as the models began to shed pieces onto the floor.

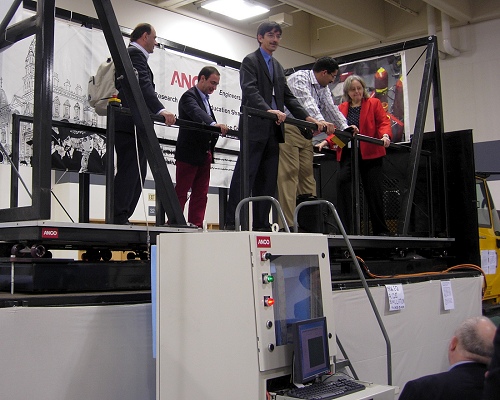

At the same meeting we could ride in a much larger apparatus as it played the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake for us. As a veteran of that quake, I found this an uncanny experience but still couldn't keep a smile off my face.

The Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center, in Richmond, is a leading institute for this stuff. (If you can get a tour, don't miss PEER's 4 Million Pound Universal Testing Machine, a steel behemoth built in 1932, and the boneyard of broken stuff out back.) It has the biggest shake table in the Bay Area, 20 feet square. That's big enough to subject a full-sized cottage or model house to a realistic earthquake experience.

The University of Buffalo used two of these at once to test a full-sized two-story townhouse in 2006 at its Structural Engineering and Earthquake Simulation Lab. (Both PEER and SEESL share resources as part of the nationwide George Brown Network for Earthquake Engineering Simulation or NEES.) In that experiment, the building danced to the tune of the 1994 Northridge earthquake. . . a break dance, you might say. Videos from the project are uncanny, period.