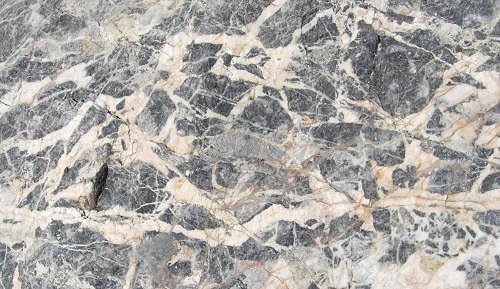

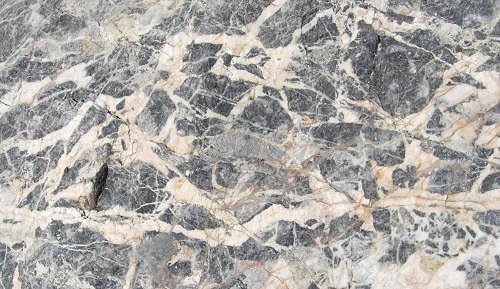

The former quarry is in the Golden Gate National Recreation Area today, and that's where my photos come from. Limestone stands out from other rocks in its color palette, usually white and gray.

The quarry exposure shows that the limestone beds are tilted almost upright. Studies of microfossils date the Calera at 88 to 105 million years old, in the middle of the long Cretaceous Period. Parts of the limestone are quite dark, thanks to a few percent of organic matter.

The Calera Limestone is not a big, thick bed of stone; rather, it's one ingredient in the disjointed Franciscan Complex that I described at Shell Beach. It's found in pods, lenses and stringers along the San Andreas fault between Pacifica and Gilroy in a group of Franciscan rocks called the Permanente terrane. Indeed, more of this terrane occurs at Parkfield, some 350 kilometers south of here.

Fault motion over the last 25 million years or so has carried this limestone north to the ocean's edge today, one earthquake at a time. You can see signs of the disruption in the rocks of Rockaway Quarry.

The natural process that shattered and recemented this rock is called brecciation. If you see a rock like this, with jagged pieces in a finer groundmass, you may call it breccia (BRET-cha).

Another sign of disruption is this slickenside, the polished surface made by faulting. It's not often found in limestone, but the Rockaway Quarry has good examples.

Another body of Calera Limestone crops out west of Cupertino, where Henry Kaiser began his entry into the concrete business in 1939 with a quarry. Whereas the Rockaway Quarry produced mainly crushed rock, the Permanente Quarry (now the Lehigh Permanente Quarry) processes high-quality limestone into portland cement. QUEST featured this quarry in 2008, including this picture of the excavation. It supplies about half of the Bay Area's cement today.

Photo courtesy KQED QUEST under Creative Commons license

Geologists have studied the Calera Limestone for many years, taking advantage of the excellent exposures in the quarry. They have learned that the limestone formed in tropical seas, far from land, as the calcium carbonate shells of microorganisms rained onto the seafloor from highly productive surface waters. The waters were shallow for an ocean basin, which means that the limestone formed on a sunken volcanic plateau or ridge rather than the flat deep seafloor. The typical limestone of the Midwest is very different, having formed in huge sheets in very shallow waters when the sea was much higher than today. In geo-speak, they are epicontinental whereas the Calera is pelagic.

The Calera Limestone plateau was carried by plate-tectonic motion from the tropical Pacific and plastered onto North America, where it remained without being pulled downward by subduction. The Calera is in pieces today not because it was torn apart during subduction, but because it formed in separate basins on a volcanic plateau and was torn apart much later by the San Andreas fault.

The upshot is that this limestone carries a precious record of conditions in the shallow Cretaceous tropical Pacific, a place and time for which we have little other evidence because subduction has removed the deep seafloor rocks. Those dark streaks in the limestone, rich in organic matter, record periods when the world ocean went stagnant and dead. They match well with similar rocks from other ocean basins, enabling us to place a signpost in time from a world now lost.

Students and professional groups visit the Permanente Quarry for open-air lessons. Photo courtesy Penny Higgins of Flickr under Creative Commons license.

37.614 -122.494

A disjointed body of rock called the Calera Limestone shows its typical colors, white to gray to black, at Rockaway Beach south of Pacifica. It has an interesting history and prehistory. Photos by Andrew Alden except where otherwise noted.

A disjointed body of rock called the Calera Limestone shows its typical colors, white to gray to black, at Rockaway Beach south of Pacifica. It has an interesting history and prehistory. Photos by Andrew Alden except where otherwise noted.