True crime series are having a moment right now. It's a perfect storm that first started brewing in Fall 2014 with Serial, a podcast that meticulously questioned the legitimacy of the conviction of Adnan Syed, for the murder of his then girlfriend, Hae Min Lee. Serial didn't just capture the nation's attention (the way no other podcast has managed before or since), it also recently resulted in the granting of a new trial for Syed.

Is America's Obsession With True Crime Re-Writing History?

A few months after Serial's enormous success, HBO unleashed The Jinx, a chilling documentary series that cataloged the life of real estate heir Robert Durst and the suspicious deaths peppered throughout his life. Durst participated in the making of the series, but a jaw-dropping finale resulted in his arrest on charges of first-degree murder. Durst is currently serving time for weapons offenses, and pre-trial hearings for the murder of Durst's friend, Susan Berman, began earlier this year.

Later in 2015, Netflix blew open the case of Steven Avery and his nephew Brendan Dassey, who were convicted of the murder of photographer Teresa Halbach. As a result of Making a Murderer, Dassey had his conviction overturned. Earlier this month, Avery had his request for a new trial denied, but his lawyer, Kathleen Zellner, has vowed to keep fighting to set him free.

All three of these series captivated America, started national conversations, and made the country wonder if we can trust our justice system to do its job properly.

In early 2016, our fascination with true crime stories shifted out of the realm of documentary and into the category of elaborate reenactment. FX series The People Vs. OJ Simpson managed the unusual feat of being both enormously popular with viewers and awards panels. It won nine of the 22 awards it was nominated for at the 68th Primetime Emmy Awards.

There were factors that made the OJ Simpson case a perfect candidate for a true-life drama series. Every minute of court time had been videotaped and broadcast as it happened, so perfectly recreating the events was possible. What's more, thanks to the fact that almost every major player in the case wrote a book about it afterwards, accurate personal information about almost everyone involved allowed the producers to portray exactly what each individual went through during the trial. As a result, The People Vs. OJ Simpson was both compelling and as factual as it possibly could be.

The problem with all of the above is that a new kind of entertainment has been born: the telling of already-high-profile true crime stories in a way that questions the outcomes of the original trials, whether they truly warrant extra examination or not.

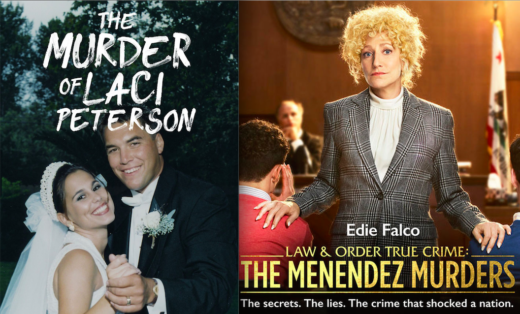

Law & Order True Crime: The Menendez Murders follows the blueprint set out by The People Vs. OJ Simpson, but with a spin. The NBC series leans heavily in sympathy of the Menendez brothers, despite the fact that the young men admitted to brutally and premeditatedly murdering their parents in 1989, then casually going on a massive shopping spree, and were convicted of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit murder.

No one will ever know for sure if the justification Lyle and Erik Menendez used in their trials—that they were sexually abused by their parents—is true or not. The difficulty in establishing this was probably a major factor in their first trial resulting in two deadlocked juries (there were separate juries for each brother in the 1993 case).

When the brothers were tried again in 1996, Time noted: "a single jury accepted the prosecution’s argument that the pair executed their mother and father in order to tap into the family fortune, rejecting the defense’s contention that the killings were a response to abuse." And yet, to watch the Law & Order rendition of the case, one could easily assume the sexual abuse allegations were proven without a shadow of a doubt.

The Menendez murder case dragged on for a full seven years and is therefore infinitely harder to summarize for a TV dramatization than The People Vs. OJ Simpson was. It also pads itself out in areas we have few means to confirm—we see "the boys" crying in their bunks at night, as well as chatting and even playing board games between the bars of their cells. It could be argued that NBC's version of this case is embellished in ways that are unjustifiable.

Also on the problematic pile is A&E's recent series The Murder of Laci Peterson, which, in re-examining the high profile 2002 killing of the pregnant Modesto woman, has suggested repeatedly that Scott Peterson might not be guilty, despite a mountain of circumstantial evidence, including (but not limited to) lying to police, refusing a polygraph, telling his girlfriend that his wife was missing a month before Laci actually went missing, attempting to flee to Mexico with a disguise and $15,000 in cash, as well as some abnormally cold behavior in the critical days following Laci's disappearance. He also told investigators he was fishing the day she went missing, in the same spot where her body was eventually discovered.

The Murder of Laci Peterson's assertion that Scott Peterson might be innocent feels less like a reveal of compelling, fresh evidence and more like jumping on the true crime / wrongful conviction bandwagon in a cynical bid for ratings. One can only imagine how painful it is for Laci Peterson's family and friends to suffer through.

Next month, Lifetime is bringing us Oscar Pistorius: Blade Runner Killer, a rehashing of a murder and trial that is still horrifically fresh in the memories of all who heard about it—especially, presumably, the grieving friends and family of Reeva Steenkamp, who was shot four times by her then-boyfriend, Pistorius. Nobody needs this dramatization so soon after the crime, and it will undoubtedly rip open wounds that haven't had time to fully heal yet for Steenkamp's family.

True crime shows can undoubtedly do a world of good when handled correctly—just this year, Netflix did a fantastic job with The Keepers (which also wins points for having the blessing of murder victim Sister Cathy's loved ones)—but it seems that, increasingly, the more high-profile the case, the more slippery the slope is when it comes to potential embellishment.

Perhaps it's time to cover the most horrific true crime cases only in documentary form, and with the blessings of the victims' families, should they still be alive. Because increasingly, we're stepping into murkier and murkier areas, and potentially re-writing history at enormous costs.