There is a high likelihood that, if you reside in the United States, it’s been a while since you’ve thought about Russell Brand. Seven years ago, the British comedian, actor and writer brought his brand of big-haired troublemaking to our screens both large and small, in a manner that felt like the beginning of something huge. So where the hell did he go?

Brand first hosted the MTV VMAs in 2008, after his breakout role in Forgetting Sarah Marshall, and immediately caused a furor after he used the spotlight to refer to George W. Bush as a “retarded cowboy,” as well as make fun of the Jonas Brothers’ pro-celibacy stance. Nevertheless, he was invited to hand out Moonmen again in 2009 and 2012, and found himself with his own Comedy Central stand-up special, as well as starring roles in Get Him to the Greek (2010), Despicable Me (2010), Arthur (2011, in a role New York Magazine described as “career-killing”), The Tempest (2011), Hop (2011), and (let’s just forget this one ever happened) Rock of Ages (2012). Arguably, though, Brand is best-remembered (stateside, at least) in the role of Katy Perry’s husband.

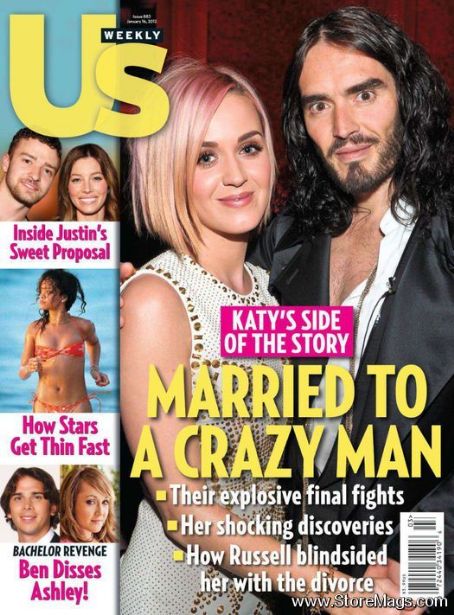

The couple’s 27-month marriage was a tabloid dream from the get-go. After their 2010 wedding in India—the basis for Perry’s performance of “Not Like the Movies” at the Grammys three months later—Marie Claire called them “one of Hollywood’s hottest pairings.” By the time Brand had famously broken up with Perry via text and filed for divorce, the cover of US Weekly screamed “MARRIED TO A CRAZY MAN” instead.

There is an assumption for many people on this side of the Atlantic that Brand’s disappearance is related to the fact that he was only famous because of Perry; that once those rings came off, his career died because he could no longer ride her coattails. (“Now he doesn’t have Katy Perry, he’s just a nobody,” we hear at the start of his Brand: A Second Coming documentary.) Others suggest that his films just never did well enough at the box office to keep him in business.

The truth is far more complex—and far more interesting.