In schools across the United States, the timeline of Native American history goes something like: Christopher Columbus, Thanksgiving, Pocahontas, Trail of Tears. Dunbar-Ortiz, who also wrote An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States, says when she travels around the country talking about Native issues, "it's as if a light goes on."

In schools across the United States, the timeline of Native American history goes something like: Christopher Columbus, Thanksgiving, Pocahontas, Trail of Tears. Dunbar-Ortiz, who also wrote An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States, says when she travels around the country talking about Native issues, "it's as if a light goes on."

"The truth is kind of depressing in a way, especially when you start talking about war and genocide and massacres," she said. "But it's as if people have been wanting to have some clarity. I don't see how anyone ever learns anything accurate about Native Americans in our education system. Even the most recent, revised textbooks are just confusing. They leave so many holes."

Those holes are large and small, and include events, people, legislation, cultural movements, wars, massacres and resistance. Many folks in the United States have no idea that there are 562 federally recognized Indian tribes in the country, let alone the unique histories of those tribes. We rarely read Native authors like Sherman Alexie, Leslie Marmon Silko or Evelina Zuni Lucero, or celebrate athletes like Maria Tallchief, Shoni Schimmel or Jim Thorpe.

Overall, Americans don't learn much about the Seminole Wars, the impact of the Homestead Act, the American Indian Movement, the historic settlement of the Indian Trust Fund lawsuit, and the ongoing debate over the Cherokee Freedmen. We don't study the dozens of Supreme Court cases involving Native Americans spanning hundreds of years, about everything from land rights to tribal sovereignty to adoption to civil liberties. We rarely acknowledge Native Americans as participants in broad American historical events and know precious little about the thousands of years of indigenous civilization that existed before European colonization.

While stereotypes persist, both authors say there is a growing hunger for information about indigenous people. "Americans know they've been lied to," Gilio-Whitaker said. "People are understanding that now, and they're mad that they've been lied to, and they want the truth."

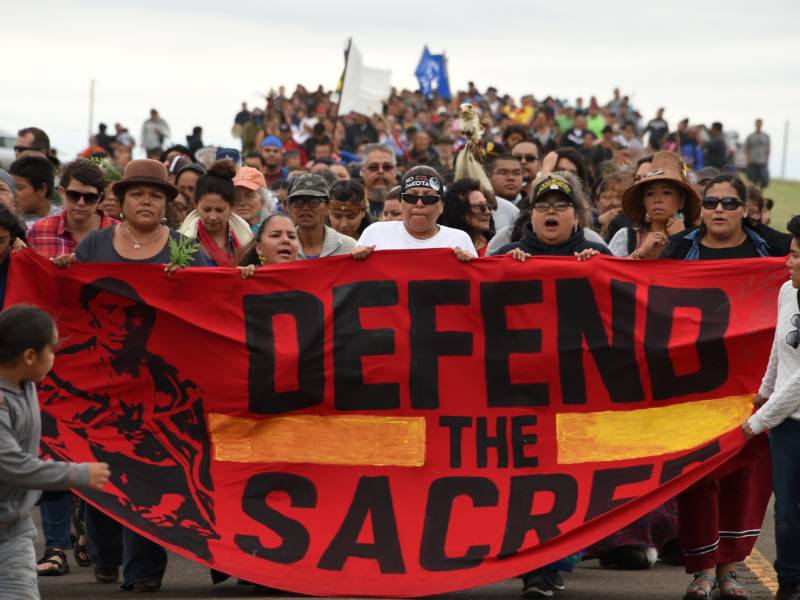

The unprecedented coalition of tribes resisting construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline on the Standing Rock reservation in North Dakota, Gilio-Whitaker says, offers a more accurate and contemporary understanding of Native Americans.

"We look at the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock and see what's happening, and how much support has poured out from the far reaches of the United States," she said. "And I'd say that it's really different compared to, say, what happened at Wounded Knee in 1973.

"There was a certain amount of support that came from non-Indians, for example with the Academy Awards and Marlon Brando making a public issue of that and rejecting the Oscar for The Godfather based on his protest of Hollywood and the way it treats Natives. That was encouraging. But for the most part, the way history has written that event, Wounded Knee, has not been friendly to Indians. They were called militants and terrorists."

Standing Rock, she says, is a different story, another part of the long, varied definition of what it means to be a real Indian.

"Indian issues are becoming everyone's issues," Gilio-Whitaker said. "Because it is about the environment, it is about environmental justice, it is about clean water, which are things that everybody can relate to now."

Copyright 2016 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))