By Maria Judnick

A Hungarian friend of mine recently told me about the work of a late nineteenth century German writer named Karl May. His novels—so popular in Europe that they still annually attract over 300,000 fans to a festival in May’s honor—feature adventurous characters exploring exotic locales: Asia, the Middle East, and the Wild West. When my friend migrated to the United States in the 1980s, as a tribute to May’s influence on her father and herself, she planned a road trip following a California route outlined in one of May’s novels. To her utter surprise, she discovered many of the remote stops still matched descriptions published more than a half century before.

That story itself is interesting. But there’s one more incredible detail—Karl May never visited his locales until after his books were published. Instead, maps, travel narratives, guidebooks, and even local novelists’ descriptions helped his vivid imagination get the story right.

I was told this story while on a retreat for Western writers. Sure, the spirit of the frontier was well-represented by all the farmers, horse breeders, naturalists, river guides, and local Oregonians I met there. But since there were hardly any Californians in attendance, the state was hardly discussed. What happened to California’s reputation as a wild place? Would Karl May still write about us?

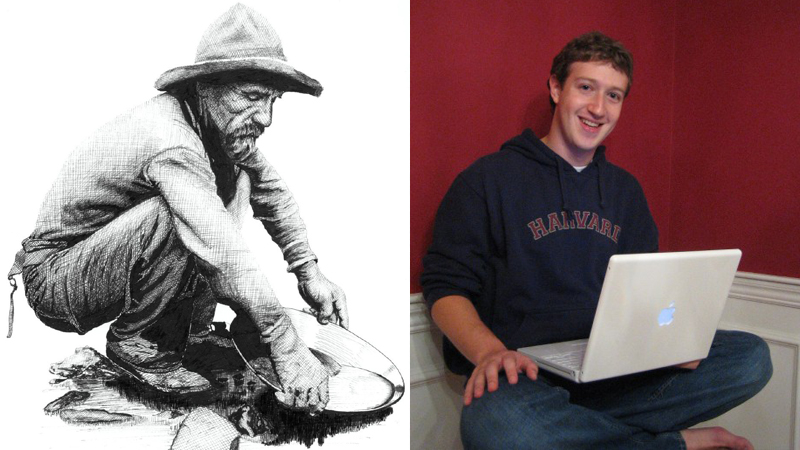

Kids who, like me, grew up in California tend to fall in love with the romanticized (and incredibly oversimplified) fourth grade history narratives of the state: the missionaries converting the natives; the early explorers and settlers’ epic will to survive; the thrilling tales of Russian trappers, Spanish ranchers, outlaw cowboys, and crusty sailors; and—the most important period leading to our statehood—the rag-tag bands of wannabe prospectors (forty-niners) who poured into California, searching for gold and the American Dream.