Two years before slavery was officially abolished by the 13th Amendment, and a full 92 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus, Charlotte L. Brown took on San Francisco’s racially segregated Omnibus Railroad and Cable Company and changed the city’s public transportation laws forever.

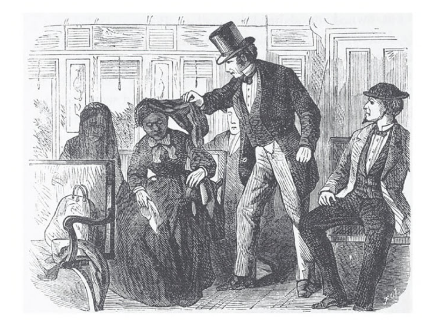

On April 17, 1863, seven months before President Lincoln had even given the Gettysburg Address, Charlotte boarded a horse-drawn streetcar, a relatively new form of transport. When the conductor reached her, he refused to take the ticket she had bought and asked her to leave, saying that “colored persons” — two percent of San Francisco’s population at the time — were not allowed to ride. Charlotte, in her early-20s at the time, had successfully circumvented streetcar segregation laws many times before, sometimes by wearing a veil. She refused to move. When a white woman joined the conductor in demanding she go, Charlotte was physically removed.

Charlotte was not one to go quietly however, thanks in large part to the way her tenacious parents had raised her. Her father, James E. Brown, made a living running his own stable, but in his personal life, James was a co-founder of the Bay Area’s first African-American newspaper, Mirror of the Times, and was an outspoken abolitionist rumored to protect fugitive slaves. James had once been a slave himself, released from servitude only when his wife, a seamstress whom Charlotte was named after, had raised enough money to buy his freedom — no easy feat.