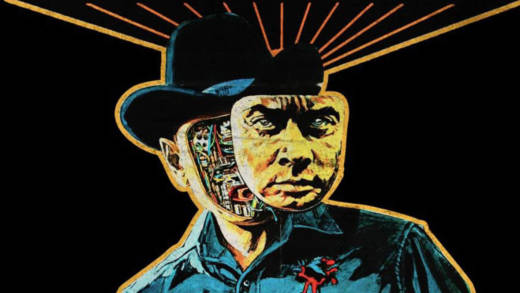

Michael Crichton, the mastermind behind Westworld (and that other nightmarish amusement park movie, Jurassic Park), understood just how immersive theme parks would, and could become, a decade before Disney's high-tech Epcot Center opened, and a full 40 years before major parks unfurled perfect replicas of the worlds of Harry Potter and Star Wars.

More than that, Westworld understood the appeal of augmented and virtual reality five years before MIT came up with its first attempt at an immersive experience (a very basic recreation of Aspen, Colorado through the seasons) and a full two decades before training simulators were first put to use by the military and NASA. The true entertainment potential of AR is only now beginning to be utilized, thanks to super-smart cell phone apps and commercially available VR headsets. Westworld's entire premise was rooted in this keen understanding of the human desire to explore alternative realities.

Westworld also understood the ways people might use advanced technology for their own sexual convenience. Both women and men are seen in the movie reveling in using the androids for sex. One tourist worries his wife will stray in Roman World, where anything goes. And another character, Peter, is a demonstration of how quickly human attitudes towards sex can shift when easy options become available. At first, he hesitates to hit the bedroom with a "machine." After being encouraged by his friend to do so, he then conducts himself bashfully. “I haven’t ever had a, uh…" he tells the robot, quaintly avoiding the term 'one-night stand'. "I feel funny." But when we see him post-coitus, he is a changed man, reveling in the ease of all this disposable sexual freedom.

These scenes aren't just a prediction about the invention of life-like sex robots (just this year, Houston City Council took steps to stop a robot brothel opening), they offer us commentary about sex and relationships in the age of tech-enhanced dating.

Westworld was so visionary, it didn't even have the language to describe things that we in 2018 take for granted. In one scene, a group of engineers is desperately trying to figure out why the resort's robots are malfunctioning in much higher numbers than usual. “There’s a clear pattern here that suggests an analogy to an infectious disease process, spreading from one resort area to the next,” one says. “Perhaps there are superficial similarities to disease," says another. What they're describing is quite obviously, to 2018 ears, a computer virus, but it was so far outside the realms of possibility at the time, one engineer in the scene scoffs, “I must confess I find it difficult to believe in a disease of machinery.”

What's more, one of the techs declares: "These are highly complicated pieces of equipment. In some cases, they’ve been designed by other computers." A fantastical idea in 1973 that's alarmingly close to reality now. Bloomberg Business reports that Fanuc Ltd., a Japanese company, currently has "several 40,000-square-foot factories, each of which contains hundreds of bright yellow Fanuc robots working around the clock to build other Fanuc robots, stopping only when no storage space remains."

Westworld was a blockbuster when it was released, and studios rushed to try and replicate its success. The 1982 sequel, Futureworld, was panned by critics, and a 1980 TV spin-off, Beyond Westworld, was such a flop, it only survived five episodes. It took another 34 years for HBO to come up with a reboot epic enough to do the original justice.

The space between Westworld seasons is interminably long—there was a stretch of 16 months between the first two, and Season 3 isn't coming until 2020, over a year and a half after the end of the second. While you wait for its return, the original Westworld is certainly worth a visit. Currently streaming for free on Amazon Prime, it's impossible to watch without wondering how many of our current-day fears around tech will eventually come true. After all, much of our 2018 reality was, in 1973, literally a horror movie.