It's been a trope for half a century: the damaged soldier returns home from war, depressed, confused and probably dangerous. There are the unhinged, Russian roulette-playing Vietnam vets of Deer Hunter. The feral ex-Green Beret in survival mode, in First Blood. The broken, drug-dependent marines of Born on the Fourth of July. The brainwashed assassins of The Manchurian Candidate. In the Valley of Elah's PTSD-addled soldiers kill one of their own. The Hurt Locker's danger-addicted Sergeant who can no longer live a civilian life. In Dead Presidents, the Vietnam vets are thieves, addicts and murderers. And American Sniper is about Chris Kyle, a Navy SEAL who was ultimately murdered by a fellow vet suffering from PTSD.

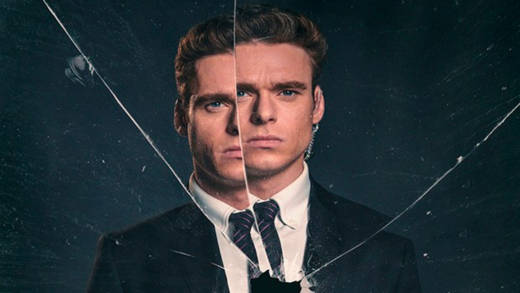

Television isn't always so heavy-handed—Modern Family's lovable patriarch Jay Pritchett served in the Navy; Geena in The Conners is a stable mom who fought in Afghanistan; in This Is Us, Vietnam vet, Jack Pearson, is a great dad—but problems persist. HBO's Barry is based entirely on the premise that Marines come home unable to do anything but kill. In Netflix's Bodyguard, one villain is a bitter former soldier hellbent on assassinating a politician. Even the hero of the piece—David Budd, an Afghanistan vet—has a wife who considers him too dangerous to live with. When Budd's lover wakes him unexpectedly one night, he launches straight for her throat, apparently overcome by killer instinct.

If you look at on-screen depictions of former service people, one could easily conclude that more come home with mental health problems than not. It's no wonder then that, according to a 2016 survey, 40 percent of adults in the U.S., U.K. and Canada "believe more than half the 2.8 million veterans who have served since 2001, have a mental health condition," even though "the actual figure lies somewhere between 10 percent and 20 percent.”

Marine veteran, Renee Pickup, served for six years, and her husband remains on active duty. She worries about the ways negative fictional portrayals of the military might impact her family.

"Most of what we see in pop culture either puts vets on a pedestal so high it's dehumanizing," Pickup says, "or it's about how damaged and dangerous everyone is. Even really well-written stuff plays into this. I adore Grosse Pointe Blank as a piece of entertainment, but [John Cusack's character] couldn’t just join the military and figure himself out. He joined the military and now he’s a hitman. Barry is another one. His only being good at killing should be presented as related to his own personal moral flexibility, not chalked up to his military experience.