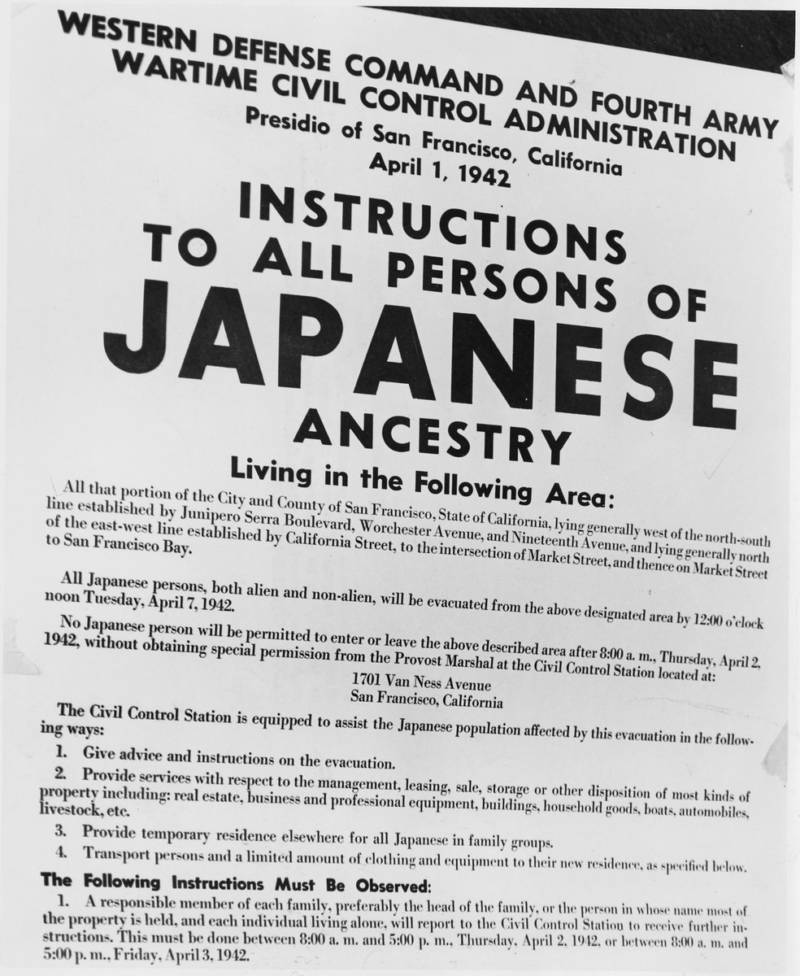

The Kataoka family managed to hang on until May of 1942. It was then—three months after Franklin D. Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066—that they were forcibly removed from their home in Alameda County and thrown into a prison camp. Across the United States, 120,000 innocent Japanese Americans were suffering the same fate; more than 8,000 of them from the Bay Area.

The Kataokas were strawberry farmers from Centerville—a region that, today, is part of Fremont. Mom Yumi and her six children—three girls, three boys—had grown even closer since the death of her husband, Masajiro, just two years earlier. But their indefinite incarceration would test the family like never before.

Yumi’s fifth child, Tsuyako, was 23 at the time of their imprisonment and already a hard worker—she worked on the family farm, a local apricot farm, and in a doctor’s office. Tsuyako had earned the nickname “Sox” as a child—the result of her peers pronouncing her name incorrectly. For her, the family’s arrival at the Tanforan racetrack in San Bruno, where they would be forced to sleep in filthy horse stables, was the most humiliating moment of her life. Sox shared one stable with her mother and brothers; while her sisters and their families moved into a neighboring one. Before their imprisonment had even begun, the family had been forced to euthanize their dog and sell off their most prized possessions—including Sox’s beloved piano.

After four months in Tanforan, the Kataokas were moved to Block 16 of a “relocation center” in Topaz, Utah. Conditions were dire in Topaz too, but it was there that Sox found her feet and first became a real force to be reckoned with. She became an assistant block manager and acted as a messenger between residents and the camp’s government officials. And, for the three years she spent there, she fought for better conditions for her community.

Within the first year, however, her entire family—except for one sister—was transferred to a different camp at Tule Lake in Oregon. But the separation served to strengthen the relationship between Sox and her boyfriend, Tom Kitashima, who was also imprisoned in Topaz. On August, 11, 1945, the couple married in the camp. And just over a month later, they were finally released.