A groundbreaking network of marine reserves off the California coast are showing promising results, according to scientists meeting in Monterey this week. The results come five years after the state set up the first group of “marine protected areas”—zones where fishing is either limited or banned all together.

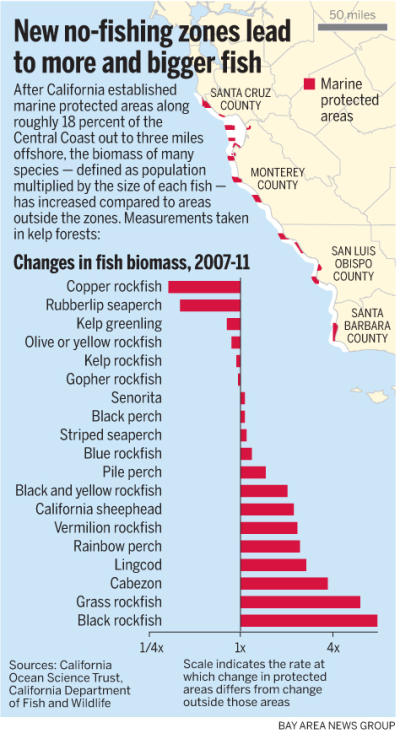

Several fish species seem to be rebounding in the 29 marine protected areas that stretch from Santa Cruz to Santa Barbara, including black rockfish, grass rockfish, perch and lingcod. Threatened black abalone are also appearing in higher numbers.

The protected areas mark a new conservation approach for the state, moving away from traditional species-by-species fishing limits. The areas were designed to protect the ecosystem as a whole, allowing fish and marine life to reproduce and recover. Scientists believe as populations increase inside the zones, they’ll spread into surrounding areas, acting as “marine savings accounts” for the entire coast.

“It’s the largest network of ecologically-based protected areas across the globe,” says Mark Carr, professor of marine biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

The areas, now covering 16 percent of state waters along the entire coast, inspired a heated battle between conservationists and fishing groups. The law that set them up, the 1999 Marine Life Protection Act, was passed just as rockfish populations crashed and the fishery was in economic crisis. Scientists made the case that the effort could eventually improve fishing outside the marine reserves.

The results released this week are the first step in proving that case. In a multi-year monitoring effort, researchers have catalogued marine life both inside and outside the marine reserves using scuba drivers, recreational fishermen, citizen scientists, and even deep-sea remotely operated vehicles. The surveys went from the rocky shoreline to 1,200 feet below the surface.