Episode Transcript

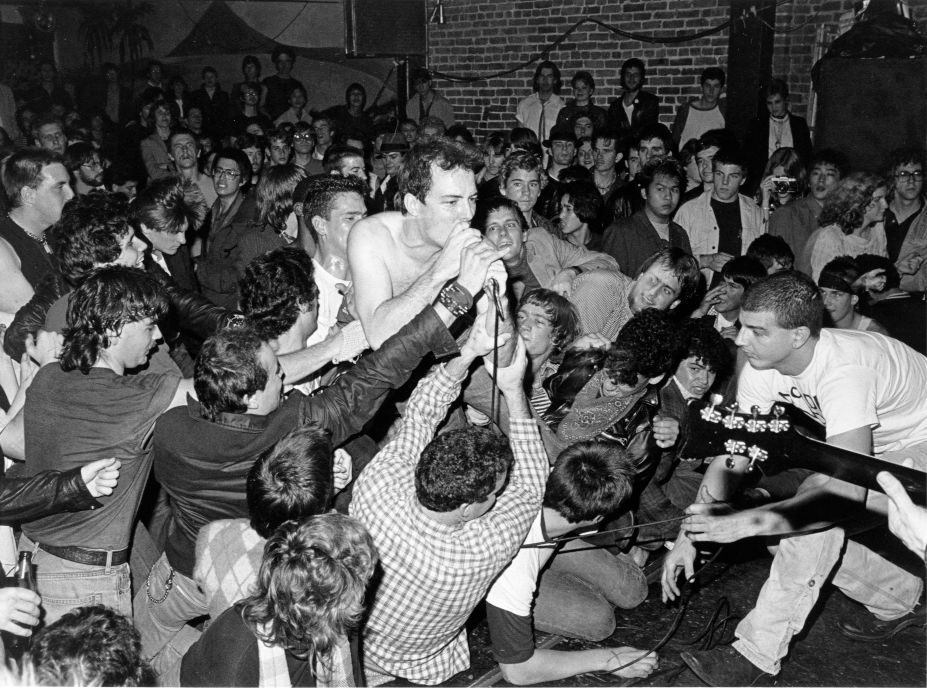

Olivia Allen-Price: John Coltrane on the saxophone is like nothing else.

Sound of Coltrane playing

Olivia Allen-Price: He grew up in North Carolina in the 1930s…where the church was a big part of his life. Both of his grandfathers were ministers. But his calling was different. After high school, he moved to Philadelphia with his mother, where his music career started to take off. …

Music plays

Olivia Allen-Price: By the mid-1950s, Coltrane was gaining recognition among other jazz musicians for the way he played, skipping scales in a style that became known as “sheets of sound.”

Music plays

Olivia Allen-Price: Here’s Coltrane in a 1960 radio interview.

John Coltrane: There’s some set things I know, some harmonic devices that I know that will take me out of the ordinary path if I use these. But I haven’t played them enough, and I”m not familiar enough, to take the one familiar line, so I play all of them so I can acclimate my ear. So I can hear.

Olivia Allen-Price: He was a famously hard worker, practicing fingering, breath control…even specific notes for hours at a time. He was even said to fall asleep with his horn in his mouth. He caught the attention of some of the most famous jazz artists of his day… playing with folks like Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis.

John Coltrane: When I started it it was a little different because I started through Miles Davis and he was an accepted musician, you see. They got used to me in the States now when they first heard me when I was here they did not like it I remember. It’s a little different. They’re going to reject it at first.

Olivia Allen-Price: But throughout these years of success, Coltrane struggled with alcohol and heroin addiction. Miles Davis famously fired him from his band for it.

And so, the story goes, Coltrane got clean, cold turkey, an experience he describes in the liner notes of his masterpiece, A Love Supreme, which came out in 1965. Here’s Denzel Washington reading them in the documentary Chasing Trane.

Denzel Washington reading Coltrane: During the year 1957, I experienced by the grace of Gd a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly ask to be given the means and the privilege to make others happy through music.

Olivia Allen-Price: A Love Supreme marked a turning point in Coltrane’s career. The album was Coltrane’s declaration to God, his commitment to love and the divine.

And it has become the sacred text of a church in San Francisco — the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church, Global Spiritual Community.

Opening riff of A Love Supreme plays

Olivia Allen-Price: Today on Bay Curious, we’re going to church to learn how a jazz musician came to be revered as a saint and how the Coltrane Church has been a part of many cultural movements over the decades, transforming alongside the city. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Don’t go away.

Sponsor message

Olivia Allen-Price: The Coltrane Church has been worshipping John Coltrane’s music, philosophy, and at times, even the man himself for 60 years. Reporter Asal Ehsanipour takes us to Sunday mass to learn more about what that sounds like.

Sounds of Coltrane Church Mass

Asal Ehsanipour: The Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church opens Sunday mass with the blow of a conch shell.

Sound of conch shell blowing

Asal Ehsanipour: Then the saxophone comes in, blaring the opening notes of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme.

A Love Supreme plays

Asal Ehsanipour: On the altar is a Byzantine-style portrait of John Coltrane. He’s wearing a white robe and clutching his soprano saxophone. A gold halo glitters above his head.

Throughout the service, the band alternates between sax, bass, and drum solos in a kind of makeshift jazz concert. Later, the sermon offered by His Eminence the Most Reverend Franzo W. King is a mix of traditional Christian teachings, and references to Coltrane.

Archbishop King during mass: Jesus is the Lord of lords and the king of kings. And that one John Will.i.am Coltrane is that anointed sound that leaped down from the throne of heaven.

Asal Ehsanipour: For Archbishop King and his wife, the Most Reverend Mother Marina, the music and their worship is one and the same.

Mother Marina King: The mission of the church is to paint the globe with Coltrane Consciousness.

Asal Ehsanipour: Coltrane Consciousness.

Archbishop King: Coltrane Consciousness is acknowledging that the music and the sound of John Coltraine is that anointed sound. So we want everybody to become aware of the power of this music, of this man, that testimony.

Asal Ehsanipour: The Kings first heard the power of that testimony in 1960s San Francisco — as a young couple in love.

Archbishop King: The music was as hip as you could get, and we were trying to be hipsters and being into this music.

Asal Ehsanipour: One weekend, 1965, Franzo and Marina planned to celebrate their first wedding anniversary. They wanted to see The John Coltrane Quartet at a club in North Beach called The Jazz Workshop.

Archbishop King: You had to be 21 and we were both underage, but I knew the doorman. And he took us right up front.

Asal Ehsanipour: As soon as Coltrane entered the room, the Kings felt the energy around them shift.

Archbishop King: When they walked out, it was almost like they were walking on a carpet of air.

Mother Marina: It was immediate. You could feel the presence, that energy.

Coltrane music starts here

Mother Marina King: And then he lifted his horn. We were right in front, and he pointed right at our table.

Archbishop King: From the first note, we were lifted into another place beyond the confines of that jazz club. And when we finished, our drinks were still on the table, the ice had melted. I don’t remember us even talking to each other.

Mother Marina King: I didn’t know exactly how to react to it. I was just in the moment of experiencing a new experience.

Archbishop King: We were caught in a windstorm of the spirit of the Holy Ghost. It was a powerful thing.

They call this experience their “sound baptism.” From then on, their calling would be to spread John Coltrane’s gospel.

Archbishop King: We couldn’t keep it to ourselves. We had to give testimony, we had to tell people.

Asal Ehsanipour: And tell people they did. Franzo and Marina had actually created a space to share their favorite music with friends — in a way, their first iteration of the Coltrane Church. Pastor Wanika King-Stephens still remembers those evenings her parents used to host.

Wanika King-Stephens: Really what that entailed was our listening clinic that took place in my parents’ living room. My mom would put on a pot of beans and make some cornbread and have people come over and they would sit and listen to the music of Thelonious Monk and Charlie Parker.

Asal Ehsanipour: Franzo and Marina poured over liner notes and interviews, spent hours absorbed in the music, analyzing it together. Then came July 17, 1967.

Wanika King-Stephens: When John Coltrane died I came into the living room to find my dad and my uncle and they had been up all night. Listening to Trane and just talking about him and the music and so when I came in the room, I’m like, “what’s what’s wrong?” You know, they said, you know, “they killed John.”

Asal Ehsanipour: Coltrane died from liver cancer, most likely fueled by his drug and alcohol addiction. But to Franzo, his death symbolized the systems of racism that targeted Black men in America.

This was a time of heightened tension for San Francisco’s Black population. The city’s so-called “urban renewal” project was in full swing and it targeted low-income neighborhoods with minority residents for demolition.

Archbishop King: The redevelopment came in with the Negro removal and devastated the community.

Asal Ehsanipour: Redevelopment brought an end to the “Harlem of the West” that defined the Fillmore in the 40s and 50s. Jazz clubs shuttered. Minority and elderly residents were forced from their homes. And the city’s Black-owned music scene was decimated. Franzo, though, was passionate that people needed to hear this music.

Archbishop King: And it was during that period, too, where so-called black consciousness was coming out. It was just a very high cultural, political things going on.

Asal Ehsanipour: So he and Marina mobilized. They opened what was essentially an underground jazz club — from their basement.

Coltrane had been outspoken about the “corporatization” of jazz. It was just one example of how he’d grown into an icon for the Black Power movement.

Coltrane’s song Alabama plays

Asal Ehsanipour: Here’s Coltrane’s 1963 song, Alabama, about the 16th Street Church bombing in Birmingham that killed four African American girls. Coltrane composed it to the rhythm of Martin Luther King Jr.’s eulogy following the attack.

Mother Marina King: So we’re living in these times of turmoil, yes it comes out in the music.

Asal Ehsanipour: But eventually, something shifted. For the Kings, the work stopped being about saving the music or the culture. It was about saving souls. Because after years of studying Coltrane, it had become clear to them that his music, his activism — his whole belief system — was really a declaration of faith.

Wanika King-Stephens: And we hear John Coltrane saying, my music is the spiritual expression of what I am, my faith, my knowledge, my being.

Asal Ehsanipour: The Kings went all in on their devotion. They converted the jazz club into a temple. Now they didn’t just revere Coltrane. They worshipped him. Believed he was the second coming of Christ.

Archbishop King: That he’s more than just a musician, but he is a prophet.

Asal Ehsanipour: And that A Love Supreme was his sacred text — his doctrine.

A Love Supreme starts playing

Asal Ehsanipour: For 32 minutes and 47 seconds, Coltrane’s saxophone pulses and intertwines with piano and drums, a four note bassline bedded beneath the sound. It’s played in all 12 keys, sending a message that you can find A Love Supreme everywhere.

Archbishop King: We hear the Lord speaking to us in this music. I’ve had John Coltrane through the music call my name. So we have revelations that come through the music. And you find that in the sound of the music, you find it in the name of the compositions.

Asal Ehsanipour: Archbishop King and Mother Marina say the album’s four song titles — Acknowledgment, Resolution, Pursuance, and Psalm — offer a formula for how to reach a higher power.

Mother Marina King: The way his notes are moving and the way the sounds are connected, it’s almost like a rumble. It’s like a war. Sometimes he’s pleading your case. Every time I hear it, there’s something new. There’s always life there. It’s in the music, the magic is in the music.

Asal Ehsanipour: Franzo and Marina surrendered themselves to Coltrane. They prayed, meditated, and fasted for days at a time.

Archbishop King: And we just felt like we were in the right place at the right time, and that the Spirit of God was really heavy in this part of the world.

Asal Ehsanipour: Around this time, The Black Panther Party was gaining traction. Started in Oakland in 1966 its co-founder Huey P. Newton had become a kind of mentor to Franzo.

Huey P. Newton: The Black Panther Party for self defense is organized now throughout the nation.

Asal Ehsanipour: Here’s Newton in 1968 describing the mission of the Panthers.

Huey P Newton: And we advocate that all Black people in America are taught what politics is all about and what our history is all about.

Asal Ehsanipour: Newton encouraged the Coltrane Church to fuse politics and culture with religion. And in 1971, the Kings opened their first permanent location in a storefront on Divisadero St. From there, they started hosting social programs, similar to the Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast Program.

Wanika King-Stephens: The food program was one of my favorite things in the whole world.

Asal Ehsanipour: Pastor Wanika says that seven days a week, they’d give free vegetarian meals to hundreds of people. The lines snaked around the block.

Wanika King-Stephens: We would sing songs, you know, ‘Serving the people makes me mighty glad. [fade under]

Archbishop King: We would go to Safeways and the supermarkets and the stuff that they would throw out. We’d take it out, put it in a tub, clean it, and serve it to the people.

Asal Ehsanipour: Franzo and Marina believed that to be right with God was to be right with the people. So they also hosted free yoga classes and donated clothes to the community.

Archbishop King: We kind of learned that stuff from the hippies.

Asal Ehsanipour: The vibe was Flower Power, psychedelics…

Archbishop King: The Grateful Dead…

Asal Ehsanipour: Utopian communes based out of old Victorian houses.

Archbishop King: The so-called hippie movement was a powerful thing and we were very much a part of that.

Asal Ehsanipour: And like the hippies, the Kings started borrowing from Eastern spirituality, led by Coltrane’s music.

Opening notes of “Om” by John Coltrane – 00:00

Mother Marina King: John Coltrane has an album entitled Om. I thought of that as far as one of the albums that meant so much to us, especially early on.

Sound of Coltrane’s “Om” playing

Mother Marina King: And we literally took that as John saying, “I am Om.”

Asal Ehsanipour: By the mid-70s, the Kings began shifting away from Christianity.

Archbishop King: We embrace the unity of religious ideas. If you want to say that Buddha is the light, we don’t have a problem with that.

Asal Ehsanipour: They incorporated Sanskrit chanting in their service.

Archbishop King chanting: That’s something that we learned from Alice Coltrane.

Asal Ehsanipour: Alice Coltrane, John’s widow, had been immersed in Hindu spirituality for years and had come to San Francisco to deepen her practice. The Kings met her here and eventually joined her new religious community called the Vedantic Center. Franzo and Marina began worshipping Alice as the wife of God and adopted Hindu names.

Pastor Wanika remembers when her parents made that shift.

Wanika King-Stephens: So we go from jazz to Sanskrit and chanting and singing, you know, Hare Krishna and Shiva, Lord Shiva.

Asal Ehsanipour: The Kings sang backup on Alice’s early devotional records, like this one.

Singing

Asal Ehsanipour: But in the early 80s, their relationship splintered. Alice filed a 7.5 million dollar lawsuit against the Coltrane Church for copyright infringement and using her husband’s name and likeness without permission. Alice eventually dropped the lawsuit, but the incident drew the attention of the African Orthodox Church, who wanted to expand to the West Coast. For the Kings, it was actually kind of similar to the temple they’d first opened except they had to recharacterize Coltrane from their God incarnate to a patron saint. They agreed.

Wanika King-Stephens: For me, John was always just sort of evolving in my consciousness. So for him to go from God to Saint was not a big stretch for me. It’s like, great, okay. I can swing with that.

Asal Ehsanipour: So in 1982, they became the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church. Now part of an organized religious movement, the Coltrane Church leaned into its status as public facing leaders. Keepers, if you will, of San Francisco culture.

Archbishop King: I think this is something people need to understand that this church has been an ambassador for this city.

Asal Ehsanipour: They traveled around the world. Like to the Antibes Jazz Festival in France — where Coltrane himself famously performed A Love Supreme in 1965.

Archbishop King: Carlos Santana joined us on the stage.

Mother Marina King: And even on airlines, we would say, hey, I saw your church advertised on United Airlines, and it would, you know, it was like a goal of places you need to see in San Francisco, and it would be the St. John Coltrane Church.

Asal Ehsanipour: But the year 2000 marked yet another shift for the Coltrane Church when they were forced out of their Divisadero storefront. Their home of nearly 30 years.

Wanika King-Stephens: It was awful, it was awful. I mean, I know I never saw it coming.

Asal Ehsanipour: Their rent more than doubled, and they had to end their free food program.

Wanika King-Stephens: We had to leave, and that was our home. That was our home. And then I watched that whole community change. And I just, I tell you, I couldn’t drive through that neighborhood without crying for, like, a whole year.

Asal Ehsanipour: They’ve relocated a few times since then. First to the Fillmore where they were one of just a handful of jazz institutions left. But they were evicted from that space too, before moving to their current location out of Fort Mason’s Magic Theater.

Sounds of Coltrane Church mass: Hallelujah!

Mother Marina King during service: This next composition is entitled Tune Gene, and it means “He who comes in the glory of the Lord.” So I want you to clap your hands, pick up your tambourines. Do we have any dancers? You know, King David danced before the Lord with all the power of his might.

Asal Ehsanipour: Now, Archbishop King and Mother Marina see the church as a kind of Mecca, where Coltrane disciples from just about anywhere can worship together. On the day I visit, they’ve come from New York, Seattle, and closer to home, Redwood City.

Archbishop King in the service: This is the St. John Will-i-am Coltrane African Orthodox Church Global Spiritual Community. Amen. So we all are family, amen.

Asal Ehsanipour: At the end of Sunday mass Archbishop King and Mother Marina asked for donations. They’re trying to raise money to buy a building. What they hope will be a permanent home.

Archbishop King: So this church needs your money. Amen. Some of y’all are holding on to God’s money now.

Asal Ehsanipour: Archbishop King and Mother Marina are in their 80s and are looking towards the future of the church, how it can live beyond them. Their daughter, Pastor Wanika, plans to take it over, to continue sharing the church’s message.

Archbishop King: So Coltrane Consciousness is a love supreme, a love supreme, a love supreme. That’s what this coltrane consciousness is all about.

Asal Ehsanipour: Since Archbishop King and Mother Marina’s sound baptism in 1965, the Coltrane Church has had different names, locations, philosophies. In fact, Archbishop King often says that as the seasons change, so do the needs of the people. Change, he says, is baked into the very essence of the church.

Archbishop King: And then at the same time, the church never changes. It remains constantly rooted in love and A Love Supreme.

Music fades out

Olivia Allen-Price: That story was reported by Asal Ehsanipour. You can attend mass at the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church every Sunday at the Magic Theater at Fort Mason.

Bay Curious is produced at member-supported KQED in San Francisco.

Our show is made by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

With extra support from Maha Sanad, Katie Sprenger, Jen Chien, Ethan Toven-Lindsey and everyone on team KQED.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by the Screen Actors Guild American Federation of Television and Radio Artists, San Francisco, Northern California local.

Thanks for listening. Have a great week.