Episode Transcript

Katrina Schwartz: Stanford University is undeniably a Bay Area icon with the pedigree to match.

Founded back in the late 19th century, this private institution sprawling over 8,000 manicured acres on the sunny San Francisco peninsula is famed for its world-class research in medicine, business, law and the humanities. It has 20 living Nobel laureates.

In short: not the kind of place you’d necessarily expect to harbor a century-old mystery full of skulduggery, lies and poison.

But that’s exactly what lies beneath Stanford’s history. Because the woman who co-founded this place, Jane Stanford, died in very strange circumstances in 1905. And although the official verdict was natural causes, some suspect something far more sinister happened.

Today on Bay Curious, we’re following the historic breadcrumbs to discover who might have been responsible. Stay with us.

Sponsor message

Katrina Schwartz: What really happened to Jane Stanford, co-founder of Stanford University, who died suddenly in 1905?

KQED’s Carly Severn brings us the historic mystery — and dastardly cover-up — that a lot of people in the Bay Area still don’t know about.

Carly Severn: Death by poisoning is a nasty way to go. But strychnine poisoning is a particularly horrible way to die.

When this white powder gets into your body, it attacks the chemical that normally controls nerve signals to your muscles resulting in overwhelming, painful spasms all over. Your jaw locks tight. Your limbs start twisting in on themselves. In high amounts, strychnine can kill you within minutes.

Strychnine tastes bitter but it doesn’t smell of anything. And as an ingredient in rat bait, and even some medicines in the 19th and early twentieth centuries, it was a very popular way to poison someone.

So what if I told you that 120 years ago, the co-founder of Stanford University found this out first-hand. And almost nobody is talking about it.

Richard White: You have to be able to follow the evidence, and I follow the evidence.

Carly Severn: Richard White is a professor emeritus in Stanford University’s history department. Several years ago he was TEACHING students how to use the university’s own archives to investigate historical conundrums … and he asked them to find out what happened to Jane Stanford.

Richard White: I thought, if I can’t get them interested in the story that supposedly somebody murdered the founder of the university, I cannot get them interested in anything.

Carly Severn: Richard found there was a lot his students couldn’t uncover about this case, prompting him to turn historical detective after the class had long ended.

When he started looking into it he was baffled this wasn’t a bigger source of intrigue. Especially because a physician at Stanford Medical School had already written a book showing that Jane Stanford had 100% been killed by strychnine poisoning.

Richard White: And the university had contended from the very beginning that she’d died of a heart attack. And that contradiction, I thought, would have a lot of public interest and certainly bring some response from the university, but it hadn’t.

Carly Severn: To get to the bottom of this mystery, let’s wind back all the way to 1828 when Jane Stanford entered this world in upstate New York.

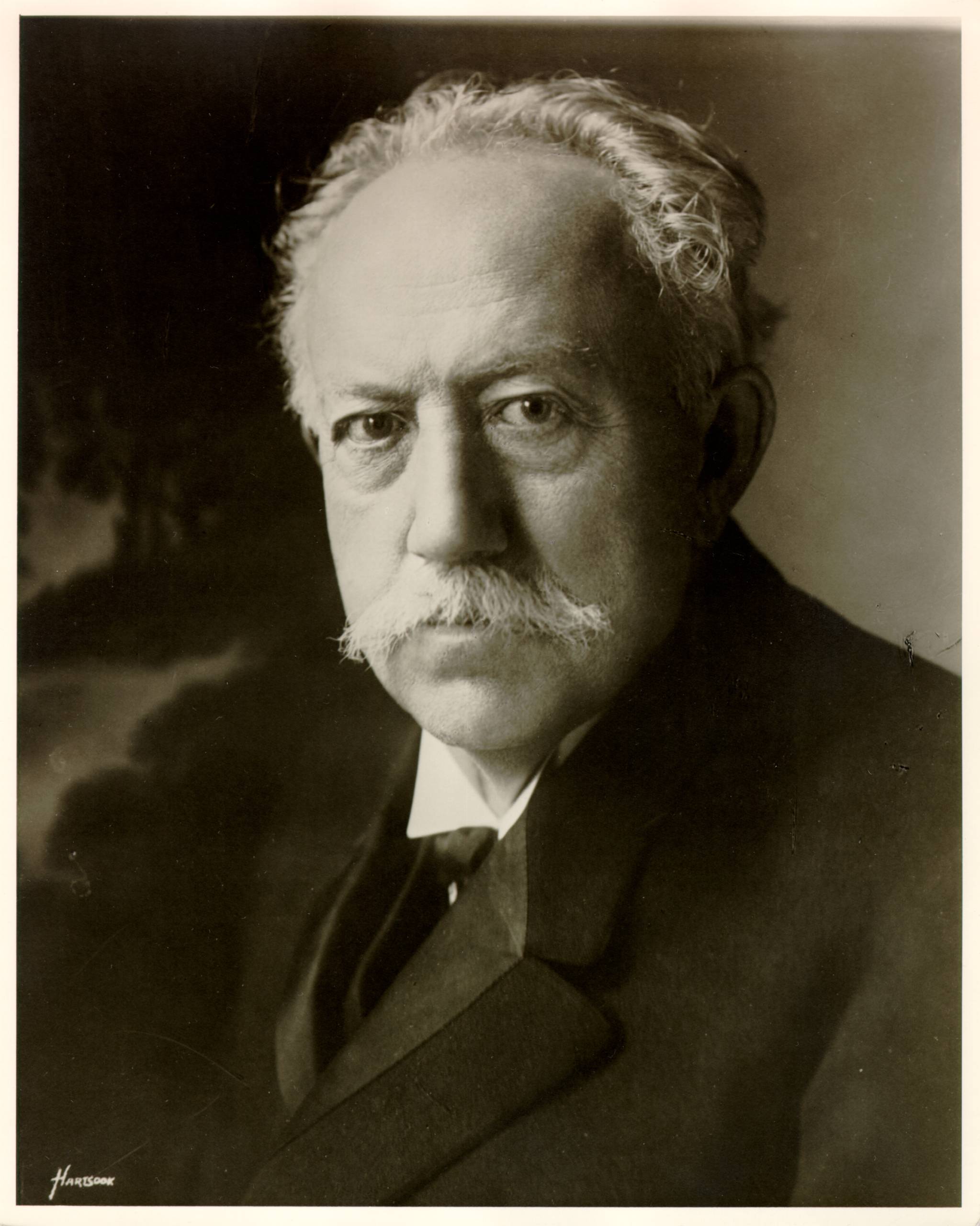

As a young woman, Jane married Leland Stanford, a businessman and politician who made his fortune in the railroad business, and who briefly served as governor of California in the 1860s.

Jane gave birth to her only child — also called Leland — when she was 39. And she doted on him.

But then tragedy struck in 1884, when that son died of typhoid. And in their grief, the Stanfords looked for ways to honor his memory.

Richard White: Founding universities and founding colleges is very much in the mind of the San Francisco elite.

Carly Severn: And so, in 1891, Jane and Leland opened a university on the Peninsula calling it Leland Stanford Junior University, after their son.

But just two years later, Jane’s husband died. And at age 65, Jane found herself in charge of the university.

Richard White: But it turned out that Leland Stanford was not nearly as competent as most people thought.

Carly Severn: Richard says Leland Stanford had mismanaged University funds and his own fortune for a long time. So for the next several years, Jane was constantly fighting to keep the university afloat in a way that wouldn’t tank her considerable fortune.

And this is really where the trouble began. Because Jane’s way of managing affairs at Stanford University made her very unpopular.

Richard White: Once she gets power she uses it ruthlessly. She knows the power of wealth and she exerts that power, so much so that she makes a great many enemies.

Carly Severn: Jane was a walking contradiction. She was an advocate for women’s rights and insisted Stanford admit female students, but treated those students terribly.

And when it came to men, Jane particularly butted heads with the president of Stanford University: David Starr Jordan.

Richard White: Jane Stanford runs Stanford University as a personal fiefdom. David Starr Jordan is devoted to the university, but he knows that the university and his own job depend on pleasing Jane Stanford.

Carly Severn: Jane Stanford was also a Spiritualist, a belief system that hinged on making contact with the dead. And like many people who turned to Spiritualism in the 19th century, Jane was motivated by personal tragedy beginning with the death of her son.

Richard White: She never gets over that. She will be in mourning for the rest of her life.

Carly Severn: But it was one thing for well-to-do ladies to be conducting seances in their free time and quite another for the leader of a major university.

Jane’s Spiritualism became a big problem for Stanford University and for its president, Jordan. Because Jane told people that she was using her seances to receive instructions from her dead husband and son on how to run Stanford.

Richard White: The great fear of Stanford University is that they’re gonna discover that Jane Stanford is a spiritualist and that’s gonna endanger all the legal documents she signs. It’s very hard to uphold the legal document when you say the ghosts are the ones telling you to sign it or not.

Carly Severn: Jane’s beliefs were a constant source of stress for Jordan. And their relationship deteriorated even further when Jane made him fire a professor friend of his, sparking a scandal about academic freedom.

And while trying to navigate all of this, Jordan made a discovery:

Richard White: He also realizes that Leland Stanford had endowed the university in such a way that the university really has no free and clear access to its funds or even a guarantee of its funds until Jane Stanford is dead.

Carly Severn: In 1905, when Jane was 76, someone tried to poison her not once, but twice.

The first attempt, at her Nob Hill mansion, was unsuccessful. Jane complained of feeling sick after drinking from a bottle of spring water and called for her staff.

Richard White: One of them was her secretary and companion, Bertha Berner, who wasn’t really a servant, but Jane Stanford often treated her like one.

Carly Severn: Bertha and the maids helped Jane to vomit. And when that water bottle was tested, the verdict came back: it was strychnine.

Richard White: But it wasn’t pure strychnine. Somebody who didn’t know much about poisoning people, had dumped rat poison in it. The rat poison had caused her to vomit. She felt very sick, but she recovered from it.

Carly Severn: The people around Jane advised her to keep the incident under wraps to prevent a scandal. And to get the hell out of dodge away from the poisoner who might try again with something even stronger than rat poison this time.

So Jane left for Hawaii with just two trusted employees: a maid and Bertha Berner.

Which leads us to the second poisoning. Just over a month after the first attempt, Jane woke up in the middle of the night in her Oahu hotel and screamed for Bertha. She knew she’d been poisoned again.

Richard White: Somebody obtained pure strychnine, put it in her water and she died within 10 minutes of the doctor coming in. The doctors looked at her, she showed all the symptoms of strychnine poisoning. Later on, the coroner’s jury would determine that it had been strychnine poisoning and that she had been poisoned by party or parties unknown.

Carly Severn: And this was the story that was reported by the earliest newspaper accounts.

Voice reads newspaper clipping: Oceanside Blade, March 1905: Mrs. Jane Stanford of San Francisco … died at Honolulu Wednesday under suspicious circumstances which point to poisoning by strychnine which had been mixed with bicarbonate of soda taken as a medicine … Mrs. Stanford had taken the medicine and retired but was soon afterward seized with violent convulsions dying in a few minutes.

Carly Severn: Naturally, Jane’s household was under suspicion. But another person absolutely had the motive — David Starr Jordan, the president of Stanford University.

Just a few weeks before Jane was poisoned the first time he’d found out that she was planning to fire him. And Richard says Jordan had also been trying to take control from Jane of those Stanford finances via some pretty shady means.

And now, Jane was dead and Jordan was on a boat to Hawaii.

Richard White: Ostensibly to bring her body home, but what he’s really in Hawaii for is to suppress the coroner’s jury verdict. He hires another doctor. He says she didn’t die of strychnine poisoning, though he has not examined the body, doesn’t know anything about strychnine poisoning, and he discredits doctors who in fact are much more senior and well-known than him.

Carly Severn: Jordan then used that new verdict to suppress the investigation back in San Francisco, which neatly concluded that instead of being poisoned, Jane had died of a heart attack.

Jordan also used the newspapers to discredit the Hawaii authorities.

Voice reading newspaper clipping: Press Democrat, December 1905: According to Dr. Jordan no strychnine was found in Mrs. Stanford’s room.

Richard White: There’s nothing to see here. There’s nothing to look at. Let’s get on with things. And it is a conspiracy to cover up her death and the conspiracy worked.

Carly Severn: Because in 1905 — before widespread telephones, before the internet — covering up someone’s death like this across an ocean no less was in many ways a lot simpler.

Richard White: For a long time, this becomes the official story from Stanford University, that she died a natural death and that she was not poisoned by strychnine.

Carly Severn: So you’re hearing all this and thinking: well, it’s so clearly this guy right? David Starr Jordan’s the murderer? He’s the one trying to cover up her death! I mean, what more do we need??

Richard White: And that’s what a lot of people think, except that the other stuff with Jordan doesn’t really add up.

Carly Severn: For one thing, he’s not present at the scene of either poisoning attempt. And he definitely wasn’t anywhere near Hawaii the second time. So while he had the motive, he doesn’t actually have the opportunity to poison her himself.

Richard White: It’s one of those times where for David Starr Jordan, you just think sometimes you just get really lucky. He wanted her killed and she was killed.

Carly Severn: So if it wasn’t David Starr Jordan, who did kill Jane Stanford?

Well if you’ve watched one murder mystery in your life, you’ve probably learned to watch out for that one “harmless” background character who keeps popping up.

And so you might be wondering, what about Jane’s longtime, long-suffering companion and secretary: Bertha Berner?

Bertha had been employed by Jane from a young age, ever since they met at the memorial service for Jane’s son.

Richard White: And Bertha Berner, by all accounts, was both a very attractive, very smart, and very capable woman.

Carly Severn: Bertha never married, which wasn’t that unusual for the time, but Richard says that was a strategic, practical decision she made.

Richard White: First of all, it would give up her job that she has with Stanford, traveling around the world, the access to a society which otherwise she would have no access to. And secondly, she becomes the sole support of her mother. She really cannot afford to give up this job.

Carly Severn: And Jane knew it. Richard says this gave her carte blanche to treat Bertha like a true “frenemy,” even going so far as to sabotage Bertha’s romantic relationships when she dared to have them.

Richard White: Their relationship becomes incredibly rocky. Bertha Berner refuses to put up with it. And several times, which rarely shows up until I started looking at it, she leaves Jane Stanford’s employ, sometimes for years at a time. But she always comes back.

Carly Severn: Another reason that Bertha stuck around through it all … she was in Jane Stanford’s will.

And this is where we come to Richard’s theory about Bertha.

Because the second poisoning attempt coincides with Bertha’s mother getting really sick.

Richard White: When Jane Stanford asked her to come to Hawaii, says, I can’t. My mother’s dying. I have to stay here and take care of her.

Carly Severn: But Jane insisted she make the journey if she wanted to keep the job.

Jane clearly still trusted Bertha and harbored zero suspicions she’d been involved in the first poisoning. Although she did have some dirt on Bertha:

Richard White: Bertha Berner has had an affair with Albert Beverly, who’s Jane Stanford’s butler at the time.

Carly Severn: Yup, there’s a shady butler in this mystery.

Richard White: Jane Stanford knows about that. And she also knows that both of them have been embezzling money from her. She can hang that over Bertha Berners head.

Carly Severn: As all good mysteries show, a killer needs the means, the motive, and the opportunity. And according to Richard, Bertha had all three.

She had the motive: anger at her years of mistreatment by Jane, fear that her embezzlement might be exposed, and financial incentive, from being in the will.

Richard White: If she can get away with the murder, she will have money in the will. She will in fact be able to continue to take care of her mother and she can set herself up not comfortably, but well enough to last for the rest of her life, which she does do.

Carly Severn: She also had the physical opportunity. All of Jane’s servants were suspects in the first poisoning, but Bertha was the only one who’d been present for both attempts.

Which brings us to the means. That first poisoning, with the rat poison, had been clumsy. But by the time Bertha left for Hawaii, Richard says she’d started a relationship with a Palo Alto pharmacist.

Richard White: He becomes a place where Bertha Berner can get free, pure strychnine. Otherwise, that would be very difficult to do.

Carly Severn: Guess the Butler was out of the picture?

Some time after Jane died, Bertha also did something really weird. She wrote a tell-all book about Jane.

Richard White: She doesn’t mention the affairs, she doesn’t mentioned the embezzling, but what she says is Jane Stanford had money and she knew the power of money. She used it like a queen. She dominated everyone around her. She got what she wanted and she forced people to do what she want them to do because she has control over her money. Which sounds very much like the reason why, in fact, in the end, she will kill her.

Carly Severn: So if it was Bertha, even if Stanford president David Starr Jordan wasn’t in on it, did he know?

Richard says he’s pretty sure the answer is yes, given how Jordan treated Bertha after the murder:

Richard White: What he does, and this he does in writing, is he reassures her that we know you didn’t do it, we’re gonna take care of you, you have nothing to worry about.

Carly Severn: And even if other people close to Jane suspected there’d been a murder and a cover-up, they didn’t want to bring that kind of smoke to Stanford.

Jane was buried in the mausoleum at Stanford University next to her husband and son. As her body was carried to her final resting place, the procession was full of people who had butted heads with her while she was alive.

David Starr Jordan — the man who led the cover-up of her murder — led the walk from the church to her tomb.

And the final insult? Walking pride of place, behind the casket, was Bertha Berner.

Richard White: The woman I think, murdered her.

Carly Severn: When you made as many enemies in life as Jane Stanford not even your funeral is safe.

Katrina Schwartz: That was KQED’s Carly Severn.

Bay Curious has published many episodes over the years that get into the spookier side of Bay Area history. If you’re looking for a little thrill this All Hallow’s Eve, check out our spooky Spotify playlist linked in the show notes.

And, don’t forget to grab yourself a ticket to our trivia night. It’s on Thursday, November 13 at KQED headquarters in San Francisco. Come alone or with a team. It will be a lot of fun! Tickets are at kqed.org/events.

Bay Curious is produced at member-supported KQED in San Francisco.

Our show is made by Christopher Beale, Gabriela Glueck, Olivia Allen-Price, and me, Katrina Schwartz.

With extra support from Maha Sanad, Katie Sprenger, Jen Chien, Ethan Toven-Lindsey and everyone on team KQED.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

I hope everyone has a fun and safe Halloween tomorrow. See you next week!