India — the largest democracy in the world — kicked off its election season on Friday, April 19. Voters will head to the polls during a period of 44 days, with results announced on June 4.

The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, hopes to further cement its control of India’s Parliament, while the opposition seeks to interrupt the 10 consecutive years of BJP government.

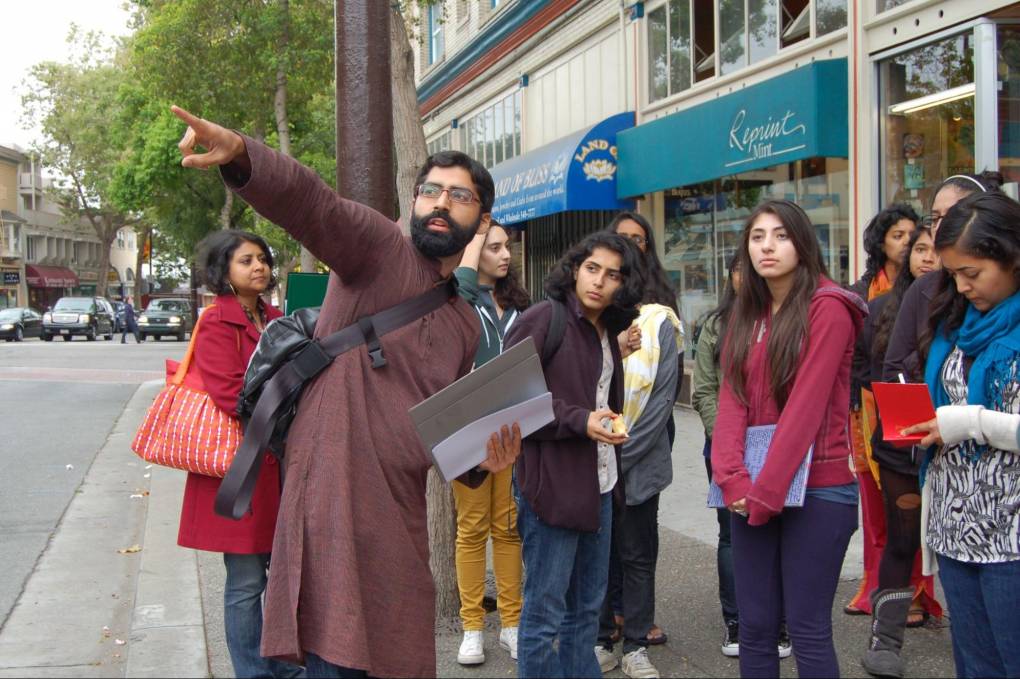

Voters in India’s election comprise over 10% of the world’s population. And for Indians and Indian Americans in the Bay Area, talk of this election may have been looming in the background for quite some time. Perhaps the WhatsApp family group chats are getting busier with videos of angry TV pundits. Or maybe your auntie and uncle are trying to reel you into policy debates.

But how exactly does India’s election work, and what’s at stake? Keep reading to get up to speed on why this election is so important for India — and the unique role the diaspora plays.

Jump straight to:

- How does the election work?

- What’s at stake? What issues are on the table?

- How does the election impact Indian and Indian American communities in the U.S.?

- I’m an Indian citizen living in the U.S. Can I vote outside of India?

How does India’s 2024 election work?

Unlike the United States, which for most of its recent history only gave voters one day to cast their ballots, India carries out its elections over several weeks to make voting more accessible to its large population.

This year’s general election period will last six weeks, starting on April 19, and results will be announced on June 4. The voters will elect 543 members for the lower house of Parliament for a five-year term.

The polls will be held in seven phases, and ballots will be cast at more than a million polling stations. Each phase will last a single day, with several constituencies across multiple states voting that day. The staggered polling allows the government to deploy tens of thousands of troops to prevent violence and transport election officials and voting machines.

India has a first-past-the-post multiparty electoral system in which the candidate who receives the most votes wins. A party or coalition must breach the mark of 272 seats to secure a majority.

Who is running in India’s 2024 election?

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party and his main challenger, Rahul Gandhi of the Indian National Congress, represent Parliament’s two largest factions. Several other important regional parties are part of an opposition bloc.

Opposition parties, which have been previously fractured, have united under a front called INDIA, or Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance, in the hope of denying Modi a third straight election victory.