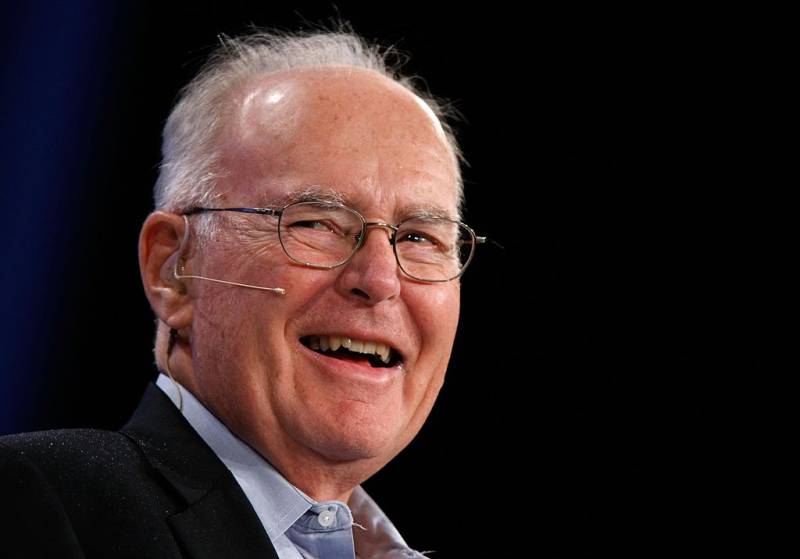

Gordon Moore, the Intel co-founder who set the breakneck pace of progress in the digital age with a simple 1965 prediction of how quickly engineers would boost the capacity of computer chips, has died. He was 94.

Moore died Friday at his home in Hawaii, according to Intel and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

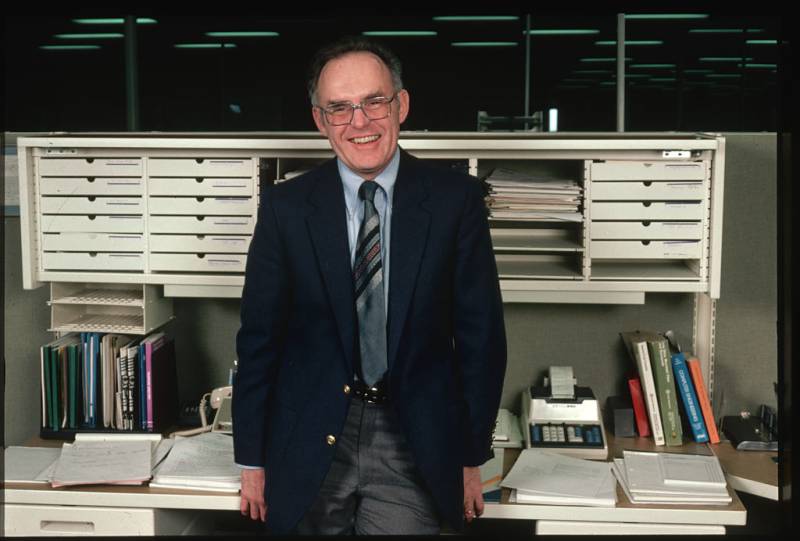

Moore, who held a Ph.D. in chemistry and physics, made his famous observation — now known as “Moore’s law” — three years before he helped start Intel in 1968. It appeared among a number of articles about the future written for the now-defunct Electronics magazine by experts in various fields.

The prediction, which Moore said he plotted out on graph paper based on what had been happening with chips at the time, said the capacity and complexity of integrated circuits would double every year.

Strictly speaking, Moore’s observation referred to the doubling of transistors on a semiconductor. But over the years, it has been applied to hard drives, computer monitors and other electronic devices, holding that roughly every 18 months a new generation of products makes their predecessors obsolete.

It became a standard for the tech industry’s progress and innovation.

“It’s the human spirit. It’s what made Silicon Valley,” Carver Mead, a retired California Institute of Technology computer scientist who coined the term “Moore’s law” in the early 1970s, said in 2005. “It’s the real thing.”

Moore later became known for his philanthropy when he and his wife established the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, which focuses on environmental conservation, science, patient care and projects in the San Francisco Bay area. It has donated more than $5.1 billion to charitable causes since its founding in 2000.

“Those of us who have met and worked with Gordon will forever be inspired by his wisdom, humility and generosity,” foundation president Harvey Fineberg said in a statement.