As a kid, Sara Trail was a bit of a crafting marvel. She was 4 years old when she started helping her mom sew. By the time she was 14, she had published a book of sewing projects and a line of patterns. On weekends, she traveled around the country teaching sewing classes.

But Trail’s relationship with sewing drastically changed when Trayvon Martin, an unarmed Black teenager, was shot in 2012. Trail identified with Martin. They were both teenagers, with birthdays only a few weeks apart. A few days after he was killed, Trail went to a quilting class. She wanted to talk about his murder and how their community could act for justice. But many of her classmates, who were older and white, didn’t understand why she was so affected by his death.

“‘You know that’s really not our problem,’” Trail recalled them saying. “‘We’re here to sew. We paid 150 [dollars] for this class. Be quiet about politics.’”

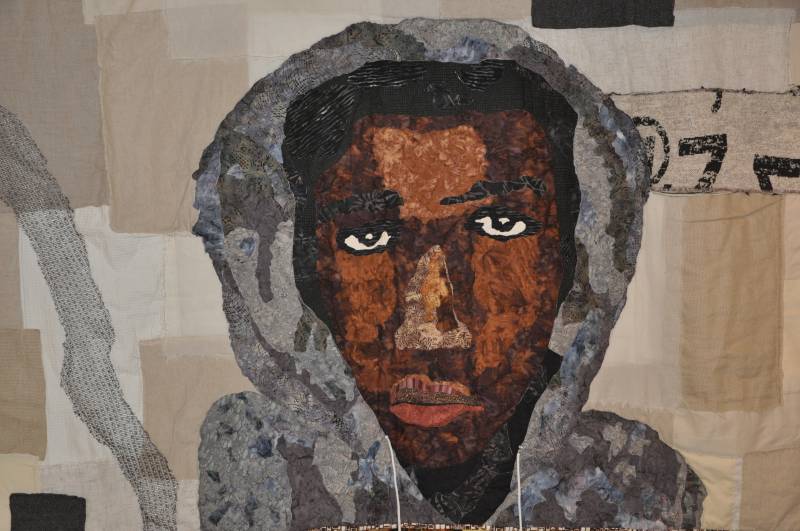

Trail sewed a portrait of Trayvon Martin, based on the now ubiquitous black-and-white photo of him in a hoodie. His young face and haunting eyes peer out from a patchwork of light fabrics. She called it “Rest in Power Trayvon.”

“It was the first quilt that I made where [I wasn’t] trying to teach everyone to make this quilt,” said Trail. “I made this quilt so we can talk about an issue that’s being silenced in this quilting community.”

But people did not celebrate this quilt like they had Trail’s other projects. Not one quilt show accepted it. Bay Area stores that proudly displayed her other work in their windows wanted nothing to do with the portrait of Trayvon Martin.

“And in that moment, I felt really shunned by an industry that I’d given not only so much of my youth, my childhood, but really my love, too,” Trail said.

She never went back to quilting traditional patterns. Her idea of what textile art could and should express expanded as she studied public policy and education at UC Berkeley. And she kept thinking about the lack of empathy the quilting community had shown when Martin was murdered. She wanted to change that.

Starting the Social Justice Sewing Academy

In 2016, the summer after she graduated from Cal, Trail was ready to teach again, but this time it would be on her terms. She created a six-week summer program on the Cal campus, open to all students, and called it the “Social Justice Sewing Academy.” By the end of the program, each student finished a quilt and wrote a research paper.

“We had kids on ankle monitors,” Trail said. “We had kids who, you know, were sagging, cussing. They were like, ‘I never thought I’d be at a UC Berkeley summer thing.’”

The students read about identity and social movements. They approached historical events from multiple perspectives, not simply those presented in traditional textbooks. Trail introduced them to textile artists like Faith Ringgold, and they discussed what it meant to be “art activists.” She admits that it was pretty academic and that the students resisted sewing at first. But eventually they got into it.

“Instead of leaving the classroom for their one-hour lunch break like they were encouraged to do, they would stay,” she said. “We would have music and they'd eat their lunch and they'd be working on their quilts.”

Six years later, that one-time summer program morphed into a nonprofit with a bevy of programs including The Remembrance Project, in which quilted banners celebrate individuals who died by violence. The group also makes memorial quilts as gifts for victims’ families and published an online Anti-Racist Guidebook.

The SJSA remains completely volunteer-run, and workshops are still at the center of their work. But now, the workshops last only a few hours or a couple of days. Instead of the Cal campus, SJSA brings its lessons to high schools, detention centers and public events. Participants no longer sew individual quilts; they use glue to create a block, or section of a quilt, centered on an issue that’s important to them.

“I definitely started SJSA as a space where anyone can become a textile artist and make their own art,” said Trail. “I think there’s something really special in making art with the purpose to be seen and to have your voice heard over and over in different communities.”

At a sewing workshop Trail led as part of the city of Sonoma’s first Juneteenth celebration, Thomas Haines made a block representing how people who identify as trans or nonbinary often don’t receive burial services that reflect their identities.

“I'm going to have the trans flag’s colors on the stripes of the hand,” they explained to fellow participants. “And then she’s pulling the cross off of the coffin because a lot of trans folks are forced to have religious funerals, even though they may not align with that.”

Haines and the other participants would also write out an artist statement explaining their design and how the issue they’d chosen affects their lives.

The blocks were then handed off to SJSA volunteers around the country to add embroidery details or embellishments the artists requested, but didn’t know how to create themselves.

For example, Haines wanted the fingernails on the hand scraping the coffin image to be embroidered with pink thread and the words “Here Lies X.”

“And then that goes off to an embroidery artist that is in a completely different class divide, a different generation, and has had different experiences,” said Stephanie Valencia, SJSA’s program coordinator. “They'll get the artist statement and they sit with that and really let it resonate.”

For many of SJSA’s volunteers, this exposure to life experiences outside their own is part of what draws them to the work.

“When I work on them, I’m thinking about what this person was thinking,” said Marcia Cary, a regular volunteer at SJSA sewing days who has worked on many blocks that deal with violence. “It’s kind of emotional.”

Despite the often difficult themes she encounters, Cary likes the work because it builds her empathy for people living lives different from hers, and forces her to reflect on her privilege.

“I think a lot of people have echoed that response,” said Martha Wolfe, another SJSA volunteer. She worked on a Remembrance Project banner honoring Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man who was chased and gunned down by three white men.

“You sit with the deceased and their families and you walk in their shoes for a few minutes,” Wolfe said. “To look into somebody’s eyes as you're creating their face … It was a good experience, but it was a hard experience.”

Prejudice in the sewing world

Not everyone is as willing to confront topics like racism, gun violence or LGBTQ equality while quilting.

Valencia says she’s been at quilt shows “where people have really negative things to say about The Remembrance Project, about Sara herself.”

Comments she’s heard range from, “‘It’s one of those exhibits of those people,’” to, “‘Why do you always talk about Black people?’”

Valencia says she can tell when prejudice is getting to Trail because Trail will remind white SJSA volunteers that their presence at quilt shows is important and ask them to put their “own community in check.”

“People of color are always deemed as the representation of their community,” said Valencia. “Anything Sara does is automatically going to turn her into ‘that angry Black girl.’ If she were to say something to defend herself, even though people are treating her with so much disrespect, it's going to shine a negative light on SJSA.”

Valencia said it’s heartbreaking to see Trail treated so rudely. “I'd be sitting next to somebody on a long bench and as soon as Sara would come over, people literally got up and left,” she said.

Jen Hewett is a printmaker and designer who identifies as Black and Asian American. She surveyed women of color about their experiences in craft spaces for her book This Long Thread: Women of Color on Craft, Community, and Connection. She wrote it in part because she didn’t see herself “represented in any of the mainstream portrayals of who practices these crafts.”

Women consistently described being the only crafters of color at events, getting mistaken for other women of color, or being followed in fabric stores because the workers thought they were going to shoplift. One of the crafters featured in the book was even kicked out of her quilting group for talking about the violent and deadly white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia.

“She was not allowed to talk about that at a quilting event when people asked her how she was, and she was uninvited because she talked about it,” Hewett said.

When people say things like, “Don’t get political. I just want to enjoy my weekend,” Hewett thinks they really mean, “Don’t disturb my whiteness. Don’t point out that as a white person, I may not have to think about this.”

Opting out isn't a choice

Trail has a message for crafters who say they don’t think discussions of racism or controversial social issues belong in hobby spaces.

“While you choose to opt in or opt out, Black bodies can’t do that,” she said. “The ability to separate is such a privilege. I wish I had it, too. When politics impact your everyday lived experience, you're going to care more.”

The lack of awareness she sees in the white quilting community has gradually become a place she focuses her efforts. In the organization’s first few years, she prioritized giving young people positive quilting experiences and finding places to display their art. But over time, she found herself more willing to educate the often older, white SJSA volunteers.

“I think as 2020 really hit, the quilting community became a lot more receptive to learning,” Trail said. “Once they learn, they can do better. It’s like a domino effect. They can bring it to their families.”

There are encouraging signs at the industry level as well. Major companies like Windham Fabrics and Aurifil have championed SJSA’s work despite criticism from customers. Political quilts by artists like Chawne Kimber and Bisa Butler are getting more attention. Garment patterns now feature more racially diverse models and come in a wider range of sizes.

“I think for me, the motivating factor is, I want to see this industry change,” Trail said. “The more little hurdles we knock over, that’s what keeps me going for months on end.”