Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Katrina Schwartz: The Transamerica Pyramid is one of the most recognizable parts of the San Francisco skyline, and was groundbreaking in many ways when it opened in 1972.

Did you know all of the building’s windows rotate nearly 360 degrees? CBS demonstrated in this news clip.

CBS newsclip: Because of the building’s unique shape, architects designed windows that could be cleaned from the inside. “Yeah but you missed a spot” spritz spritz 3,676 to go…

Katrina Schwartz: The pointed peak of the building is a 212 foot spire, reinforced by aluminum grating. KRON4 climbed to the top to check it out in 1998.

KRON4 newsclip: This is the spire … oh my god…

Katrina Schwartz: The now famous building just got a $400 million dollar makeover and in the process builders uncovered something surprising

News clip: But deep within its steel bones there, construction crews discovered a time capsule.

John Krizek: There was always this tradition of putting time capsules in buildings under construction. I’m John Krizek and I was the public relations manager of Transamerica Corporation from 1968 to 1977.

Katrina Schwartz: John and his friend Bill Bronson, who was the editor of the California Historical Society, planted the capsule back when the Transamerica Pyramid was being built in the early 70s.

John Krizek: I think it was our intent at the time that this was going to be locked up and not looked at for 50 years.

Katrina Schwartz: They put in cassette tapes, photos, maps, recipes, and newspaper articles that would show whoever found the capsule how the spot where the building stands has played an important role in San Francisco history since the Gold Rush.

John Krizek: We needed to save that history. And on top of that, on this sacred site, we come along with this shocking plan for this unusual building, which went through an enormous amount of controversy.

Theme starts

Katrina Schwartz: Today on Bay Curious, we’re digging into the history of the Transamerica Pyramid. It’s one of the most iconic San Francisco buildings and yet there’s a lot I didn’t know about it. We first aired this episode in December of 2022 in honor of the pyramid’s 50th birthday. I’m Katrina Schwartz, filling in for Olivia Allen-Price. Stay with us.

Theme ends

Katrina Schwartz: The Transamerica Pyramid is iconic now, but you will not be surprised to learn when it was new, people hated it. KQED reporter Carly Severn takes us back in time to the birth of a legendary landmark.

Carly Severn: Like a pin in a map, the Transamerica Pyramid marks the spot where the communities of Chinatown, North Beach, Telegraph Hill and the Financial District all converge.

And in terms of the city’s history, the site that the Pyramid is built on is hallowed ground.

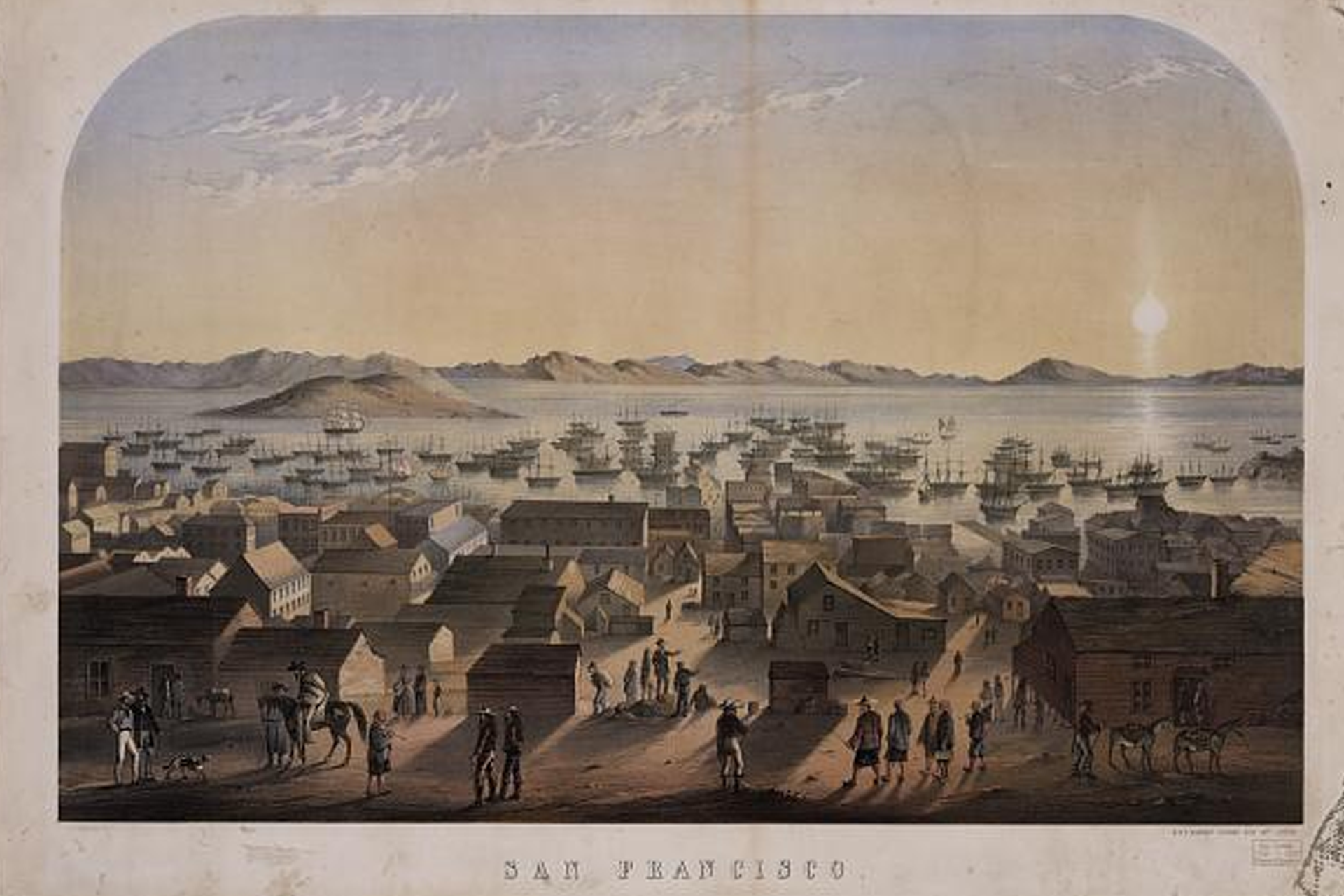

In 1849, the year the Gold Rush began, this part of San Francisco was right on the water. So close, that a whaling ship called the Niantic was deliberately run aground right here after the crew abandoned ship to seek their fortunes in this wild, wily town.

The coast didn’t stay “the coast” for long. Landfill was used to rapidly swell the San Francisco streets further out into the Bay – swallowing that shipwreck with it.

But back when this part of Montgomery Street still bordered the bay — in 1853 — it was a good place to construct a huge building, one that spanned the entire block.

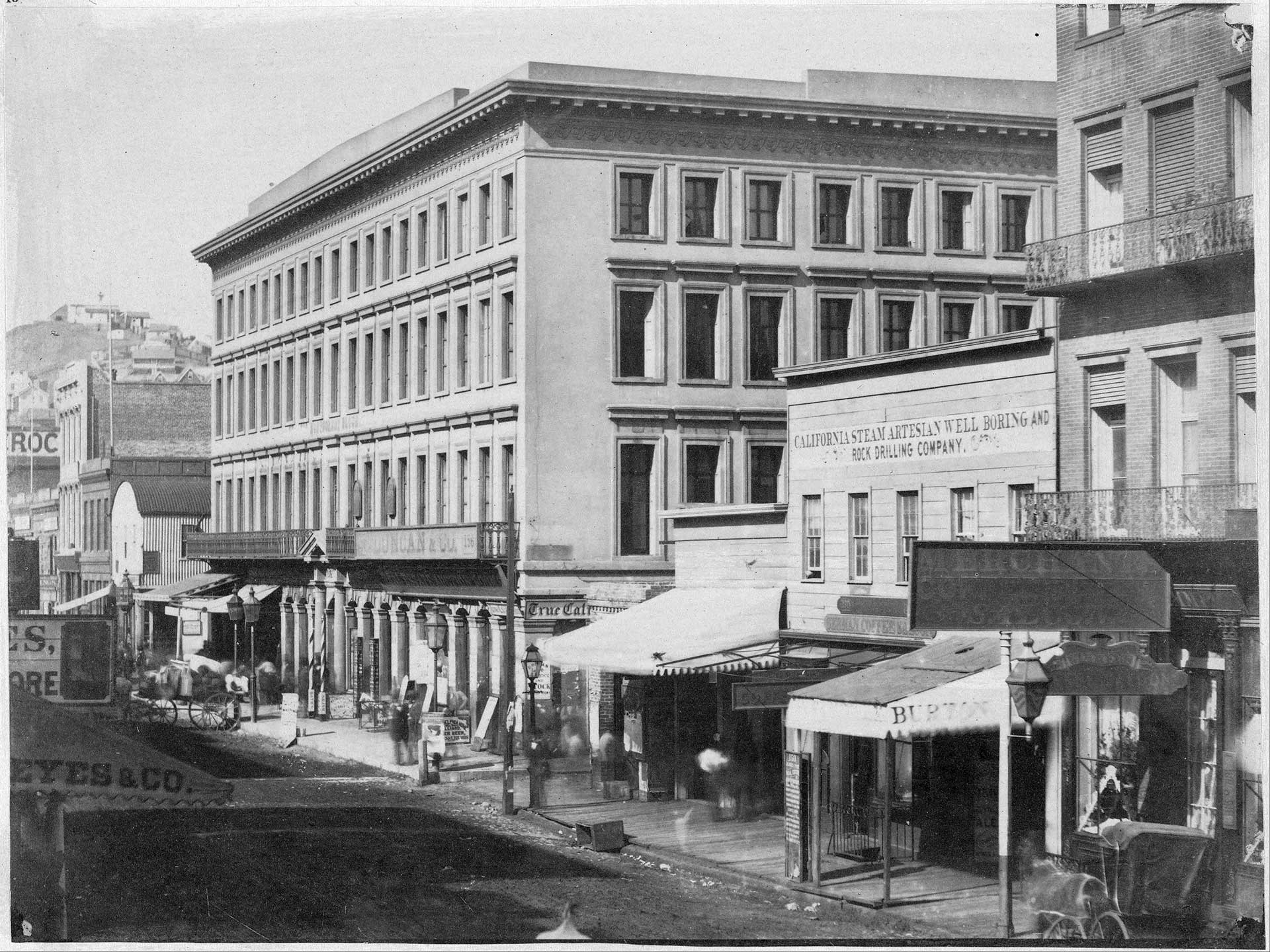

They called it the Montgomery Block. And the history of this building has long fascinated San Francisco writer Hiya Swanhuyser.

Hiya Swanhuyser: It was the tallest building west of the Mississippi. At a towering four stories, it was famously built on a foundation of a so-called raft of redwood logs that had been floated across the Bay.

Carly Severn: Like so many places in San Francisco, the Montgomery Block, and the people inside it, lived many lives. This space was originally built to be law offices, with a hangout spot for high society, but when the city’s business folk started to migrate to Market Street, the creatives moved in.

Hiya Swanhuyser: They were writers and sculptors, people who were inventing journalism in the mid 1860s. People like Ambrose Bierce, who according to some, was America’s first newspaper columnist.

Dramatic read of Amrose Bierce writing: Corporation: An ingenious device for obtaining profit without individual responsibility.

Hiya Swanhuyser: And Mark Twain and Bret Harte.

Dramatic read of Bret Harte writing: The only sure thing about luck is that it will change.

Hiya Swanhuyser: And Ina Coolbrith, who was California’s first poet laureate.

Dramatic read of Ina Coolbrith writing: Were I to write what I know, the book would be too sensational to print, but were I to write what I think proper, it would be too dull to read.

Carly Severn: Just a block to the north, now-iconic artists Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera lived and worked here in the 1930s. It was a scene.

Hiya Swanhuyser: It sort of stayed a scene for most of its life, which ended in 1959 when someone bought it and tore it down to make a parking structure.

Carly Severn: But the garage never materialized. And so the space remained a single parking lot for almost a decade.

Enter the Transamerica Corporation.

This business actually started in San Francisco back in 1904 as the Bank of Italy, courtesy of a local man called A.P. Giannini. Later, in the thirties, it would become known as Bank of America. Ever heard of it?

Giannini had a lot of financial schemes and he soon needed more than a bank to contain them. That’s when the Transamerica Corporation was born. By 1969 the Corporation was ready to make its mark on San Francisco with a new headquarters.

They brought in a Los Angeles architect named William Pereira to design it. He was told to create something that would still allow light to filter down to street level.

But when the design for the 763 thousand square foot pyramid dropped, the critics hated it.

The San Francisco Chronicle’s architecture writer Allan Temko called it

Dramatic reading of Allan Temko: Authentic architectural butchery.

Carly Severn: And it wasn’t just local critics. The Washington Post said Pereira’s Pyramid proposal was:

Washington Post voice over: A second-class world’s fair space needle.

Pastier voice over: Antisocial architecture at its worst.

Carly Severn: Said Los Angeles Times critic John Pastier. He captured a broader unease about Transamerica trying to smear its corporate vision on the San Francisco skyline:

Pastier voice over: Corporations that are far more important to the city have exercised considerably more restraint in their architecture than Transamerica, which is blatantly attempting to put its ‘brand’ on the city.

Carly Severn: People protested against Pereira’s pyramid design, carrying signs that bore slogans like “Corporate Egotism” and “Stop the Shaft.” They even wore pyramid-shaped dunce hats.

These protesters actually included Hiya Swanhuyser’s own mother:

Hiya Swanhuyser: She was a community minded hippie and she didn’t think that a neighborhood was the right place for a skyscraper.

Carlyn Severn: Neighborhood residents even filed a lawsuit. At a City Hall hearing about the proposal, an attorney for the Telegraph Hill Dwellers Association spoke for those residents, in language that echoed the burgeoning environmentalism of the sixties:

THDA Attorney: The curse of this country is the worship of material things. We’ve polluted our rivers, our harbors, and our lakes, and our air. And we’re now about to pollute the skyline of San Francisco, one of its greatest treasures.

Carlyn Severn: But at that same hearing, San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto quoted the classics in support of the pyramid.

Joseph Alioto: We have to recognize that the Latinists used to say ‘De gustibus non est disputandum’ – that there simply is no disputing tastes, and the only question is whether it is so bad that all reasonable men must agree.

Carly Severn: And this pyramid, Alioto said, wasn’t that bad. On the contrary:

Joseph Alioto: It will add considerable interest and beauty to the San Francisco skyline.

Carly Severn: The city’s Planning Commission signed off on the project and the pyramid was officially coming to San Francisco.

Construction on the Transamerica Pyramid started in 1969, a dark year in many ways. This was the year in which three of the four confirmed murders by the Zodiac killer took place – the last one in San Francisco itself.

News clip: School children are nice targets, I shall wipe out a school bus one more and then pick off the kiddies as they come bounding out. That was the threat of the zodiac killer.

Carly Severn: The year that you could open the Chronicle and read the Zodiac’s cryptic letters full of codes and symbols right there at your breakfast table.

News clip: They are weighing advice from astrologers on the theory that the killer who calls himself the Zodiac may be planning his next victim based on astrological signs.

Carly Severn: ‘69 was also the year of the gruesome Manson Family murders in LA, with all their Satanic imagery.

News clip: One officer summed up the murders when he said, “in all my years, I have never seen anything like this before.

Sneak up Rolling Stones set at Altamont Festival

Carly Severn: Of the disastrous Altamont Festival outside Livermore

Rolling Stones: Hey People!

Crowd noise

Carly Severn: A celebration of counterculture that devolved into violence, mayhem and murder.

Rolling Stones: Why Are we fighting?

Carly Severn: So I can’t help thinking how it would have felt to be living in San Francisco at the start of the 70s, bombarded with so much occult-inflected darkness in your morning paper – and seeing one of the most ancient and mysterious symbols, a pyramid, being summoned in your backyard.

But for many, watching a skyscraper go up was also exciting.

Larry Yee: My name is Larry Yee, born and raised in San Francisco.

Carly Severn: Now, Larry is the president of the historic Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, also known as the Chinese Six Companies. He also serves on the San Francisco Police Commission.

But back in 1969, growing up in Chinatown’s Ping Yuen housing development, Larry was a basketball-obsessed teen, running – or often skating – around this part of the city with his friends.

Larry Yee: Play hide and seek — you know, we challenge ourselves and go into some of these vacant buildings that they developed.

Carly Severn: Walking around the base of the Pyramid over 50 years later, with the sound of traffic and tourists echoing off the street corners, Larry says the San Francisco he remembers from childhood, pre-pyramid, looked quite different:

Larry Yee: Yeah. It was flat! You know, there weren’t many buildings like this that pop up through the skyline.

Carly Severn: This part of town was hopping, and full of the kinds of characters that had frequented the Montgomery Block years back. It was home to famous nightclubs like the Hungry I and the Purple Onion comedy cellar, where folks like Lenny Bruce were playing.

Lenny Bruce: Where I’m goin’ kill it.

Carly Severn: But when the Pyramid was being built, all Larry and his friends could get was a sneak peek through the holes in the plywood fencing that hid the rapidly-rising behemoth.

And he still remembers the sheer, constant construction noise.

Larry Yee: You come home from school and you know they’re pounding down on the pillars. Bam, bam, bam, bam.

Carly Severn: Initially, he and his friends didn’t even know it was a pyramid. They just saw a building being built up, and up, and then up even further, getting narrower.

Larry Yee: We had concerns too, how far it’s going to go, whether it could tip over and then once they finished we said “Ah, this is a pyramid.”

Carly Severn: When it was finished, Pereira’s pyramid had over 3,000 windows, an exterior of white quartz, and an illuminated spire at its very top, like the star on top of a Christmas tree.

Subtle, the pyramid is not. But decades on, Larry’s still a fan of this building. He says for him, it represents progress — the meeting of the old and the new. And he’s fond of its place in the visual fabric of the city, and the neighborhood, he’s always called home.

Larry Yee: I don’t know. It’s magical.

Carly Severn: And it’s funny. For a building that’s literally built on the site of the Montgomery Block, where creative genius flourished; a building whose design was so fiercely contentious, the Transamerica Pyramid Center is now thoroughly uncontroversial.

Its silhouette on our skyline has become symbolic of San Francisco. Even several of those early critics changed their minds. Henrik Bull, an architect who originally opposed the pyramid — publicly, and loudly -– told the San Francisco Chronicle on the building’s 40th anniversary that like many others, he’d switched course in the intervening decades:

Henrik Bull voice over: What’s good about the Pyramid overwhelms what’s bad about it. It’s a wonderful building. And what makes it wonderful is everything that we were objecting to.

Carly Severn: What started out as a corporate symbol has stayed, well, corporate. In a Financial District full of office buildings, the pyramid is in many ways just another one of them.

The Transamerica Pyramid isn’t even the Transamerica headquarters any more — those officially moved to Maryland. These offices are primarily leased by financial services companies dealing in wealth management and private equity. There’s even a high-end members club moving in soon. A 21st-century Montgomery Block artist’s haven this is not.

But here’s another thing: For the most visible local icon you could imagine, the Transamerica Pyramid is not very public. Tourists might naturally assume that a trip up the pyramid is one of the City’s must-see attractions — like climbing the Empire State Building or the Space Needle. But you can’t go inside the Pyramid Center, let alone climb to the top to see the view, unless you’re visiting one of the offices inside. There used to be an observation deck up there, but it closed in the nineties.

Still, the ghosts of this site’s previous inhabitants linger here, if you know where to look.

If you go to the Pyramid today, and walk into the small park at its base, you’ll find Mark Twain Place, named after one of the Montgomery Block’s most iconic inhabitants.

And remember that old ship that ran aground here in the Gold Rush, back when all this was bayside? The Niantic?

It wasn’t lost to time after all. Later in the ‘70s, way after the pyramid was built, a construction team working in the park discovered what was left of that ship, right here. Pushed down over the decades by a city that has been remaking itself since Europeans arrived, buried deep underground. It’s said that champagne bottles were even found resting in its hull.

And just steps away from these markers of our past is the once-hated pyramid. A symbol of the city’s money and power, but an accepted icon nonetheless.

Katrina Schwartz: That was KQED’s Carly Severn.

You can go see the items preserved in the time capsule in the lobby of the renovated building. And checkout the redwood park while you’re there.

Bay Curious is produced in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. Our show is made by Gabriela Glueck, Christopher Beale and me, Katrina Schwartz. With extra support from Alana Walker, Maha Sanad, Katie Springer, Jen Chien, Holly Kernan and everyone at KQED.

The Bay Curious team is taking next week off for Juneteenth, but we’ll be back with a brand new episode on June 26th!

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

Thanks for listening! Have a great week.