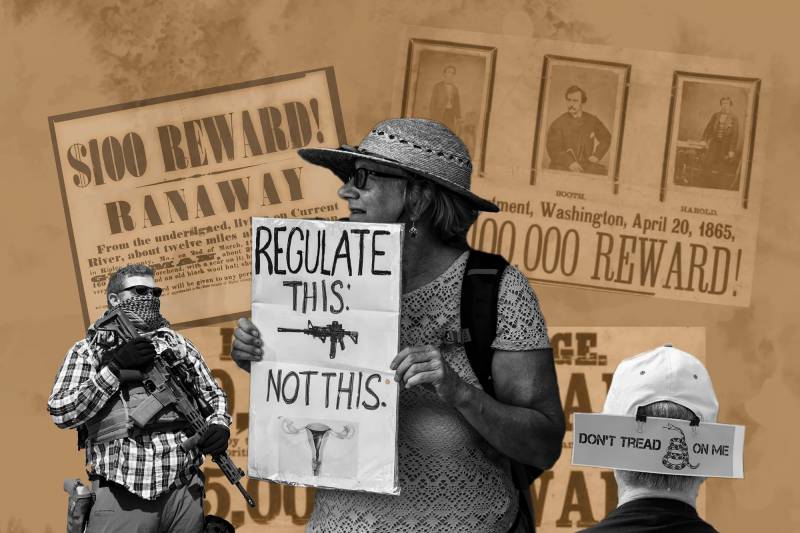

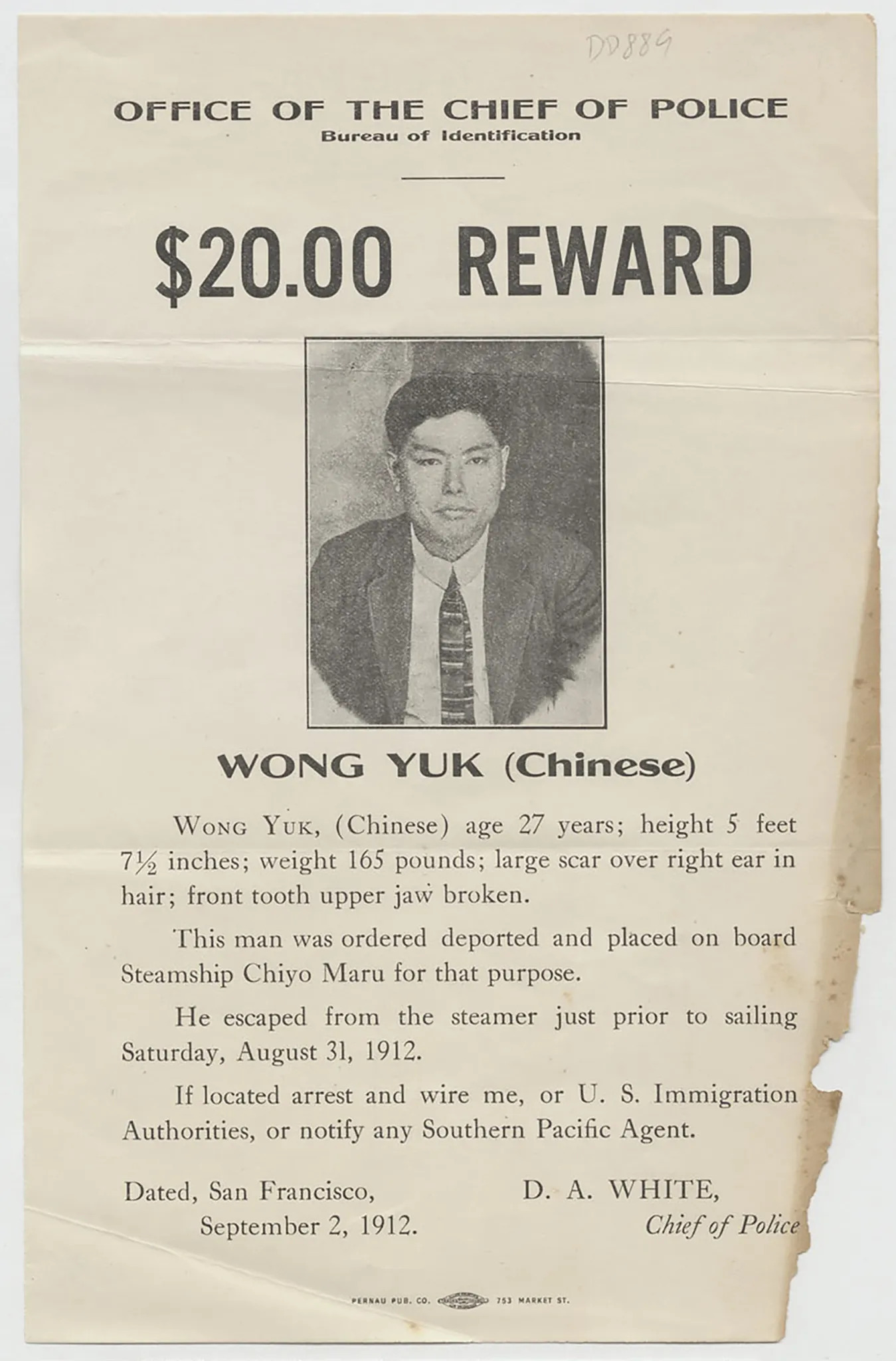

In Texas and California, new laws call on the people of each state to watch and report their neighbors — and reap a reward for doing so. Unusual, yes — although it’s a concept that dates back to the earliest days of the American republic.

But what do Civil War-era legislators raging about sick mules and wet gunpowder have to do with Texas Senate Bill 8, its “heartbeat” abortion law, and California Senate Bill 1327, its newest gun act?

They all set out bounties, with the state entrusting its citizens to enforce the law and promising remuneration to those who do.

The Texas law, passed in 2021, bans abortions if a doctor detects a fetal heartbeat, usually at about six weeks — but it’s not up to the state to enforce it. Instead, people anywhere in the United States can sue anyone who helped a Texan get an abortion. Successful lawsuits offer at least $10,000 per reported abortion, and the defendant, not the state, pays the plaintiff.

As U.S. Chief Justice John Roberts noted, the law ran contrary to abortion rights guaranteed under Roe v. Wade, then the law of the land. Instead, he wrote in a concurring opinion, “Texas has employed an array of stratagems designed to shield its unconstitutional law from judicial review.”

Opponents included the firearms industry, which started getting nervous about the implications for gun owners.

Sure enough, by the time the U.S. Supreme Court later jettisoned Roe’s right to abortion, perhaps making the machinations of Texas unnecessary, California was already fighting fire with fire.

Last month, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bounty law targeting not abortion but guns. It allows private citizens to sue anyone for $10,000 for selling, distributing or importing ghost guns or assault weapons.

A new legal challenge to the Texas law was filed in April. Gun rights supporters have promised to challenge California’s law as well.

Entrusting the public to enforce the laws and paying them with bounties was once how this country kept the lights on — or, at least, the lanterns lit.

“Before you had a really strong central state, and before you had a professional civil service, a lot of government services were provided on a bounty or a fee-for-service basis,” said Stanford Law School professor David Freeman Engstrom.

To catch wrongdoing back then, the state had to rely on people watching their neighbors — and maybe hauling them to court.

Today the U.S. government rewards people who report fraudulent war contracts, terrorism, violations of federal environmental law and Medicaid fraud. The state of California allows financial rewards for people who sue to enforce its Proposition 65 toxics warning law.

And, of course, there’s bail-jumping, for which we still have “professional” bounty hunters, though the subjects of bail bounties sign a contract surrendering many of their rights.

Not all bounties pay in money, Engstrom said — under federal environmental laws, a nonprofit is only able to recover attorney’s fees, from a successful injunction either against a polluter; against other violations of environmental law; or to protect an endangered species of animals. But the nonprofit is also able to demonstrate to potential donors that they’re “doing important work out in the world,” he said.

The Texas and California bounty laws are relatively novel now, said University of Georgia School of Law professor Randy Beck, but he worries about what could come next.

“There’s a long history with these things that is not very happy,” Beck said. “There’s a good reason that legislators have stopped using them, and I think I’m worried that a bunch of legislators are repeating history that we don’t want to repeat.”

‘We’ve created a monster’

One of the first bounty laws in history was enacted in England in the early 1300s. Local officials were supposed to set uniform prices for wine, but some of them were also wine sellers. That conflict of interest complicated King Edward II’s effort to reassert political control over a fractious kingdom.