In a canyon filled with makeshift shelters, a mile south of the U.S.-Mexico border, farm animals linger near a stream clogged with trash.

For Migrant Kids Stuck in Tijuana, This School Offers a Place to Grow and Dream

For over two years, thousands of migrants seeking refuge in the United States — many of them children — have crowded into a network of shelters here, as two successive U.S. presidential administrations closed almost all access to asylum at the Southwest border.

One morning in March, on a patio behind a wooden fence along the canyon, classical music played from portable speakers as a teacher readied art supplies for her students. At this school, called Canyon Nest, all of the students, and many of the teachers, are migrants — many fleeing violence in their homelands — waiting to enter the U.S. The school serves over 100 students, ages 3 to 10, who attend free of charge, five days a week.

Ten-year-old Gabriel is one of the first through the door and gives his teachers big hugs. He’s especially excited because tomorrow is his birthday.

Gabriel came here with his mother and 4-year-old brother in August, from the Mexican state of Michoacán, where drug cartel violence has exploded in recent years. He started attending the school in September.

“What I like most here is to help my classmates with the subjects they have difficulties with,” Gabriel said in Spanish, explaining that he’s one of the older students at the school and already knows some of the material being taught.

He says the patio is his favorite place at the school, which is filled with playground equipment, toys and even a resident kitten.

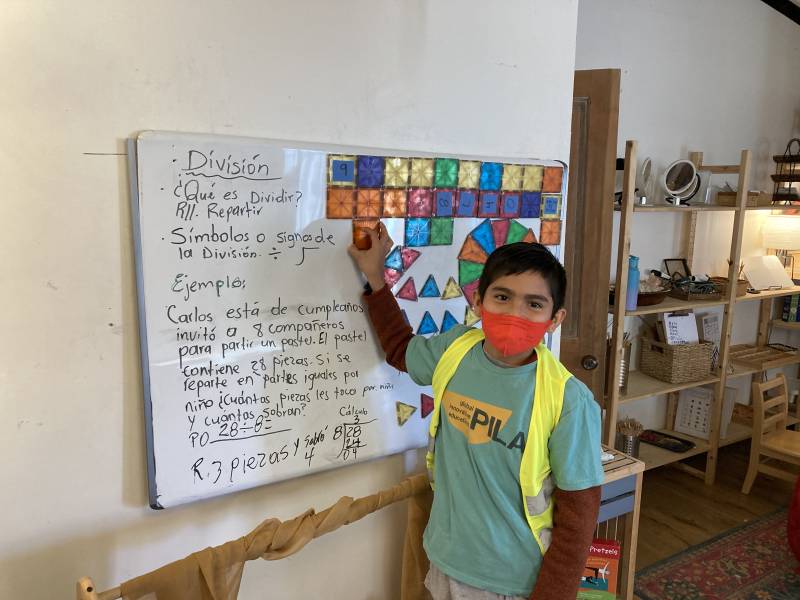

The school, run by PILAglobal, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit, opened its first school in 2018 in a more residential Tijuana neighborhood to accommodate kids in the large migrant caravans that began arriving in the city.

But after learning of the thousands of migrants crowded together in this canyon, the program quickly marshaled resources to build a new location here, which opened its doors in 2020 just before the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The organization, which also operates school sites serving migrants in Greece, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zimbabwe, is funded by a variety of private donors and foundations, and partners with organizations like UNICEF.

Gabriel says he hopes to someday become an English teacher in the U.S.

But he says here his favorite class is math, which is taught by Walter Orlando Campos, a veteran elementary school teacher from Honduras.

“Science, social studies, math, Spanish, art,” Orlando Campos said in Spanish, ticking off the subjects he taught back home.

Orlando Campos says he would have loved to stay in Honduras the rest of his life if conditions hadn't deteriorated.

“I didn’t want to go. I left because of the political crisis there,” he said. “It became too complicated for me to live there, and I saw no other way to escape the violence there than to leave.”

Orlando Campos has been in Tijuana since July, and says the school allows him to earn some extra money, and to continue teaching students.

Working here also has benefited his own mental health, he says, which took a big hit after his life was uprooted.

“It’s my passion to teach students. When I arrived in Tijuana, I couldn’t find anywhere to work, I wasn’t happy at all, I couldn’t enjoy anything. But when I found [this school], I felt refreshed. The children transmit ... so much positivity,” he said.

The school starts out every day with a song greeting each of its students. The goal, says PILAglobal CEO Lindsay Weissert, is to give children a break from the immense stress of migration.

“All children deserve to feel valued, and all children deserve to have a space where they can just be children, away from adult conversation where past violence against them may be retold,” she said.

Glenda Linares, the site’s program director, who migrated to the U.S. from El Salvador as a child, says the school also gives parents some much-needed time for themselves.

“When they go home to the shelter, the parents have attention and energy to be with their children. The parents are holding a lot of their own stories and journey, and their own trauma,” she said. Parenting classes, she notes, also are offered on weekends.

In an effort to meet the growing demand, PILAglobal is now expanding the school into the hillside of the canyon and plans to be able to serve more children later this spring. The group also runs a mobile classroom that circulates to shelters in Tijuana, and a small playroom for children near the San Ysidro border crossing.

Since August, Doris — who gave only her first name — has been working as a classroom helper at the school, which her daughter attends. The two fled violence in the Mexican state of Guerrero, and tried to cross the border into the U.S. last June, hoping to claim asylum. When border patrol agents thwarted their passage, they ended up at a nearby shelter and soon learned of the school.

Doris says working is giving her a chance to feel positive about her life again.

“When the kids call out to me on the street, ‘Teacher, teacher,’ I’m so proud they’re saying that,” she said.