Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Patricio Ginelsa: The running joke of Daly city is that the reason why it’s so foggy is because everyone opens up the rice cookers at the same time.

Katrina Schwartz: This is Patricio Ginelsa. He directed the indy cult classic Lumpia and its sequel, Lumpia with a Vengeance.

From Lumpia With A Vengeance Trailer: All my sexy Pinoys and Pinais!

Katrina Schwartz: The fictional Fogtown in the film is really his hometown…Daly City.

From Lumpia With A Vengeance Trailer: Welcome to fogtown where over 60 percent of the population is Filipino.

Katrina Schwartz: Patricio shot the first Lumpia movie when he was home on summer break from USC film school. His friends are the actors, his neighbors the extras….and the Filipino food staple lumpia… his hero’s weapon of choice.

From Lumpia With A Vengeance Trailer: It’s not a taquito. It’s Lumpia, the Filipino eggroll.

Katrina Schwartz: It’s a very fun film…an action comedy, but deals with the sensitive issue of discrimination against newer immigrants within the Filipino community.

Patricio Ginelsa: It gave me an opportunity to talk about these experiences through a wacky comic book filter.

Katrina Schwartz: I met up with Patricio at his old high school, Jefferson High, where he shot scenes for both movies. Growing up he didn’t realize how unique it was to be surrounded by so many Filipino people.

Patricio Ginelsa: I thought it was like this everywhere else in the United States at that point.

Katrina Schwartz: But Daly City is not like everywhere else. Filipino people are not a minority here..a fact that’s apparent to anyone who works in the community. Ricky Tjandra, our question asker this week, used to help international students find homestay placements. Many families he worked with in Daly City were Filipino.

Ricky Tjandra: I noticed that there’s a large Filipino population in Daly City and I was always curious about the origins of that and how it came about.

Katrina Schwartz: Daly City does have a large Filipino population, about 30%. But it wasn’t always this way. After World War II, a lot of the houses built in Daly City were in whites-only developments like Westlake. We made a Bay Curious episode all about that history — I’ll put a link to it in the show notes. Check it out.

Today, we’re going back more than a hundred years to explain the complicated relationship between the US and the Philippines, why so many Filipino people chose to settle in Daly City, and how this place has become a cultural touchstone for Filipinos around the world. This episode first aired in August of 2021.

I’m Katrina Schwartz and you’re listening to Bay Curious.

Sponsor Message

Katrina Schwartz: Producer Amanda Stupi used to live in South San Francisco and has family in Daly City. She’s spent her fair share of time hanging out at the Serramonte Mall food court. And she’s been looking into why Daly City is such a hub for the Filipino community. Hi, Amanda.

Amanda Stupi: Hi, Katrina.

Katrina Schwartz: I know the relationship between the U.S. and the Philippines goes back a long way. When do we see immigration from the Philippines begin?

Amanda Stupi: Filipino immigration to the US goes back to the 1890s.

By then, the western United States had seen a lot of immigration from Asia and many white people resented that immigrants from places like China and Japan were starting to buy land and farm.

Dan Gonzales: And then in nineteen twenty four, there was a strong push nationally, not just statewide, but nationally to exclude Japanese immigrants, but what they did was they said why just exclude Japanese immigrants? Let’s exclude them all.

Amanda Stupi: This is Dan Gonzales, professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State. Back then, the Philippines were technically part of the United States because after the US military drove the Spanish out of the Philippines, the Americans decided to occupy the islands and colonize them.

Dan Gonzales: Because the American flag flew over the Philippines they couldn’t be excluded, Filipinos could be restricted, but they couldn’t be excluded.

Amanda Stupi: At the same time, California was becoming an agricultural powerhouse. Farmers and businesses needed cheap labor. They found it in the Philippines. Thousands of young Filipino men came to California to harvest crops like asparagus.

Dimitri Ente Jr: The hardest work I ever done was asparagus. You had to get the asparagus out of the fields because during the hot day, the sun will soak up the liquid in the grass, the asparagus.

Amanda Stupi: That’s Dimitri Ente Jr, who was interviewed in a PBS documentary about Stockton’s Little Manila neighborhood.

Dimitri Ente Jr: When working in the grass, the wind was just blowing on that peat dust. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. I wore two pairs of pants, 3 shirts, a bandana over my head, a scarf and goggles.

Amanda Stupi: During the Great Depression of the 1930s displaced people flooded into California looking for jobs. Jobs Filipino immigrants were already doing. That set the stage for conflict. Gonzales says that animosity spurred the US government to once again limit immigration, this time from the Philippines.

Dan Gonzales again.

Dan Gonzales: It was just as much race, as it was for economic reasons.

Amanda Stupi: Immigration from the Philippines dried to a trickle until World War 2.

Amanda Stupi: By the time the war broke out…the US had seen 50 years of immigration from the Philippines. Thousands of those immigrants joined the military to fight the Japanese in the Pacific.

Dan Gonzales: My father was one of them, my father, my and my wife’s father, my generation, just about all of our fathers.

Amanda Stupi: Many of those soldiers… who’d fought in the Pacific… met and married wives in the Philippines. That led to a second wave of immigration…this time with women and children.

Amanda Stupi: Gonzales’ mother married his father a couple of years after the war, giving him time to save up for a wedding and … Gonzales teases, for his mother to be

Dan Gonzales: Courted properly. Right.

Amanda Stupi: When she first arrived in San Francisco, Gonzales’ mother and father worked at Golden Gate Nursery…a huge operation that sold flowers to the Colma cemeteries.

Dan Gonzales: There was a big nursery, one of the biggest in Northern California. And the anchor crew was mostly Filipino.

Amanda Stupi: Gonzalez says the nursery workers were some of the first Filipinos to buy houses in Daly City. And when they moved on — often for jobs down the peninsula — they sold their houses to other Filipino families. That’s likely how Filipino Americans started to build a community in Daly City.

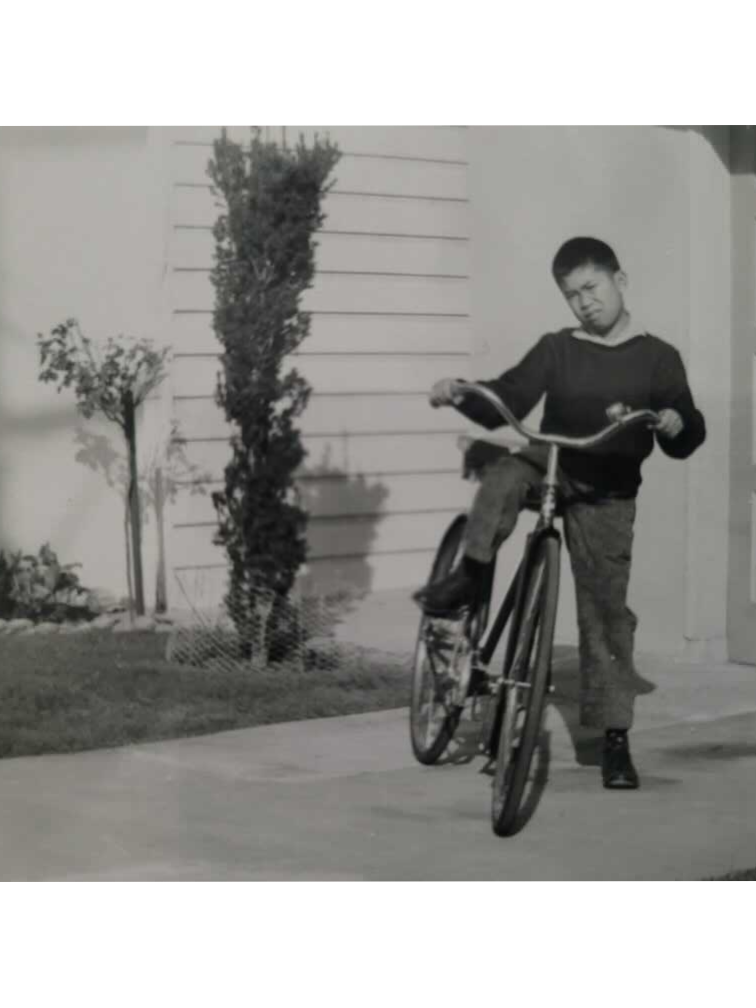

Dan Gonzales: They started moving out to Daly City as early as the mid and late 50s, but they were relegated to the area to the east of Junipero Serra. And typically to the older homes that were built in the 20s and 30s.

Amanda Stupi: These houses weren’t part of big developments…and didn’t have rules about who could…or couldn’t… live there like some Daly City neighborhoods.

Dan Gonzales: There was always an issue of, you know, will the white people let you live there? I mean, it was very clear that white people had the power to exclude.

Amanda Stupi: Dan Gonzalez remembers growing up in the South of Market area ….one of the few places Filipino families could rent when they arrived in San Francisco.

Dan Gonzales: I have really vivid recollections of segregation.

Amanda Stupi: After saving up money, his parents started thinking about moving. He remembers a time in the 1950s when they were driving around and stopped to look at a house that was for sale. The real estate agent went to ask the owner about showing it to Gonazales’ parents.

Dan Gonzales: He talked to the owner for a couple of moments, walked down the stairs very slowly and he walked up to the driver’s side of the car where my father was sitting and and said, I’m sorry, Mr. and Mrs. Gonzales, but the owner refuses to show you the house and he has the right to do that.

Music starts playing

Dan Gonzales: And you know, my dad, who had been here since before the Second World War, he knew about that. And so he knew he had to accept that when my mother, who had not come here until after the Second World War, was shocked by it, dismayed by it. And I tell you, I think she cried for three days because one of the few times that she didn’t go to work the next day, she never missed work.

Amanda Stupi: Gonzales’ family did eventually buy a home and settle down in San Francisco’s Excelsior neighborhood, now a thriving, diverse neighborhood.

Music

A small but steady stream of Filipinos continued immigrating to the US through the 1960s. Then, immigration policy shifted in a major way.

In 1965, the U.S got rid of its racist immigration policy that kept Asian immigrants out. The law now favored people with education or who had family already in the United States. Many Filipinos had both.

Dan Gonzales: As the Filipinos arrive after 1965, some of them are not only educated, but they are experienced. They actually have been working in their professions in the Philippines. And so they’re recruited to pretty decent jobs.

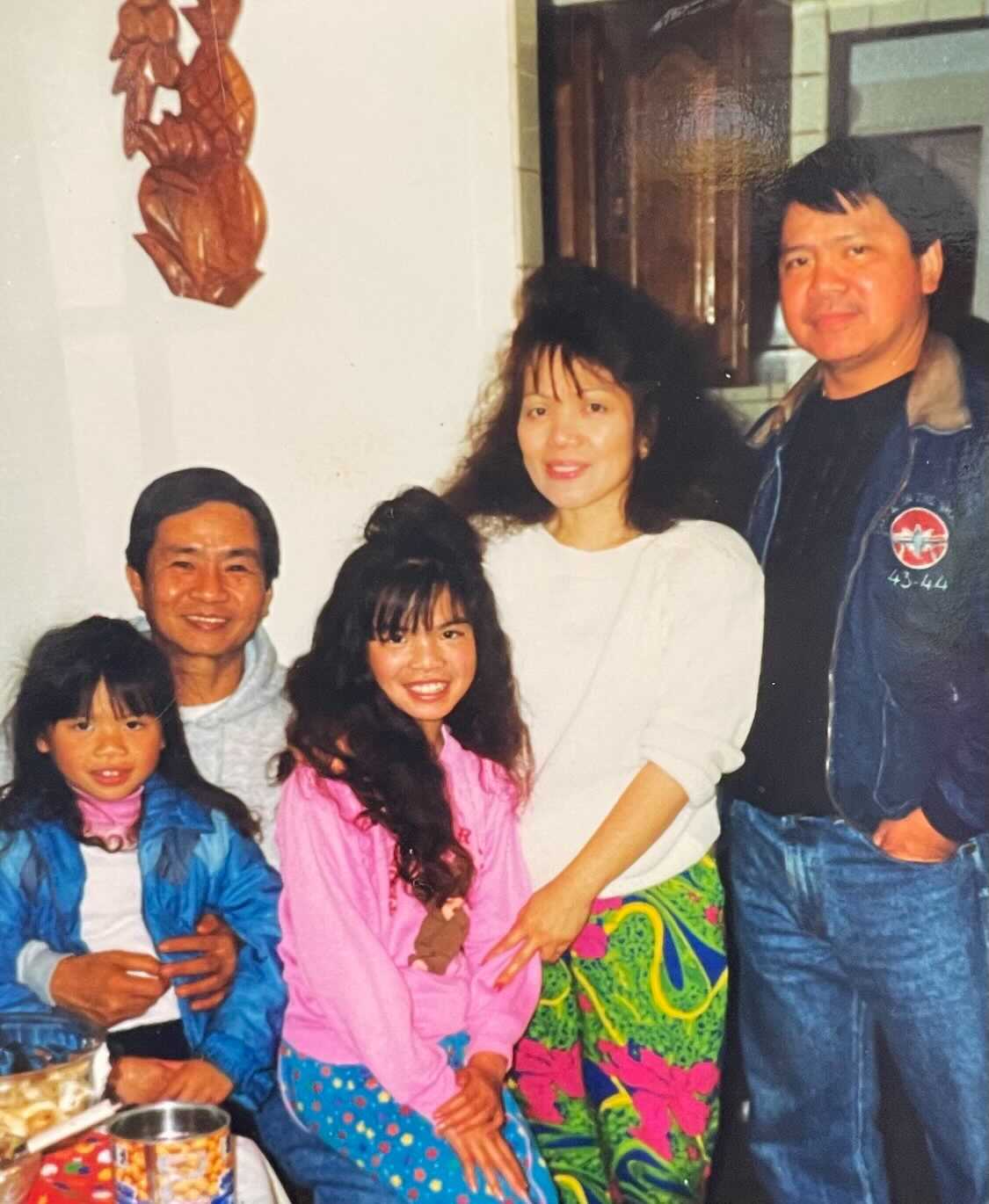

Amanda Stupi: One of those people was Josie Manalo.

Juslyn Manalo: My mother, Josie Manolo, she came in 1974 as a single woman and she came here, you know, of course for a better opportunity.

Amanda Stupi: This is Daly City mayor Juslyn Manalo.

Juslyn Manalo: She came to be a teacher over here, but her story is when she went to get her kind of first assignment, they gave her the sixth grade class. you know, she’s five feet. she was in culture shock.

Amanda Stupi: Like a lot of immigrants, Juslyn’s parents moved directly to San Francisco where there was a Filipino community and jobs. And then, after saving up money, and growing tired of living in a small apartment, they moved to the closest, most affordable suburb — Daly City.

Juslyn Manalo: As an eight year old I thought it was so far. I mean, going on a freeway, I was like, oh, my gosh, I’m moving so far. And in hindsight, it was actually so close.

Amanda Stupi: Around this time, San Francisco planners were tearing down and “redeveloping” the Fillmore and South of Market neighborhoods. So whether they wanted to leave or not, the Filipinos living in those areas needed another affordable place to live and many found that in Daly City.

By this time the Fair Housing Act of 1968 had passed, making housing discrimination based on race illegal. That set the stage for Daly City to become the diverse place it is today.

Music

Juslyn Manalo: When there is family that moved to a certain place, then other family members will move close by. And I think that’s also, you know, how the population grew.

Amanda Stupi: And people in the Filipino community help one another. It’s a cultural value called bayanihan.

James Zarsadiaz: So when folks say they’re doing something in the bayanihan spirit, what they’re often referring to is doing something for the greater good, for the community at large.

Amanda Stupi: Here’s James Zarsadiaz, head of the Yuchengo Center for Filipino Studies at the University of San Francisco.

Zarzadiaz says the Bayanihan spirit has helped Daly City thrive. Now it has something a lot of other Filipino communities around the country don’t have.

James Zarsadiaz: International name recognition among Filipino Americans and Filipinos around the world, you can say Daly City and they know where that is because they probably have a friend, a relative, some family member or connection that lives in Daly City.

Amanda Stupi: The Filipino Channel is headquartered in Daly City. There are dozens of Filipino restaurants and bakeries. And the Filipino fast food restaurant Jollibees picked Daly City for its first U.S. location.

James Zarsadiaz: It may not be the Philippines itself, but you have access to the goods, to friends and social networks that make it easier for them to feel more comfortable and to kind of ease into a new landscape and new way of life.

Music in

Amanda Stupi: Mayor Juslyn Manalo is from a generation of Filipino Americans who grew up surrounded by these tastes and sounds of Filipino culture.

James Zarsadiaz: It’s part of their identity. They grew up with these spaces, these foods, these traditions. And it’s a big part of who they are and how they see themselves as part of a wider network and community.

Amanda Stupi: Now Manalo is committed to making Daly City a welcoming place for people of all backgrounds. She says she owes it to her elders.

Juslyn Manalo: So I’m a beneficiary of those that were leaders way before my time.

Amanda Stupi: The Filipino and Filipino-American roots run deep in Daly City. More than 70 years. You can see it at City Hall. There’s this wall with photos of past mayors.

Juslyn Manalo: You’ll see kind of the change along the years, there was heavily Caucasian men on that wall and then finally a Caucasian woman. And then further down the line, you saw diversity. So you know, there has been that change that reflects the population.

Amanda Stupi: Over the last three decades Manalo says Filipino Americans like her have been showing up on that wall.

Katrina Schwartz: That was producer Amanda Stupi.

Be sure to check out our other episode about why Daly City is so densely populated. We’ll put a link to it in our show notes. You’ll also see a link to donate there. As you may have heard, funding for public media is in jeopardy right now and we need folks like you to step up and support the show. Every little bit helps. We really appreciate it.

Bay Curious is a production of member-supported KQED in San Francisco.

Our show is made by Gabriela Glueck, Christopher Beale and me, Katrina Schwartz. With extra support from Maha Sanad, Katie Springer, Jen Chien and everyone at team KQED.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.