There was a day in early December when Maria Cruz thought she might not make it.

“One morning my chest was in so much pain, I began to cry because honestly I panicked,” she said, recalling the cough, body aches and shivers during the grueling weeks she spent with COVID-19.

So when her employer, Monterey Mushrooms in Morgan Hill, offered its employees vaccines allotted by Santa Clara County, she drowned out anything negative she’d heard about the shots and signed up.

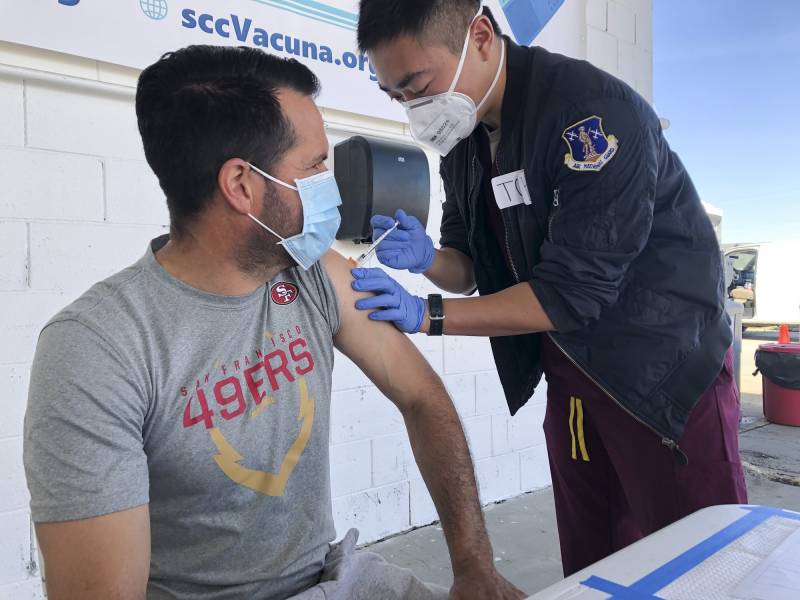

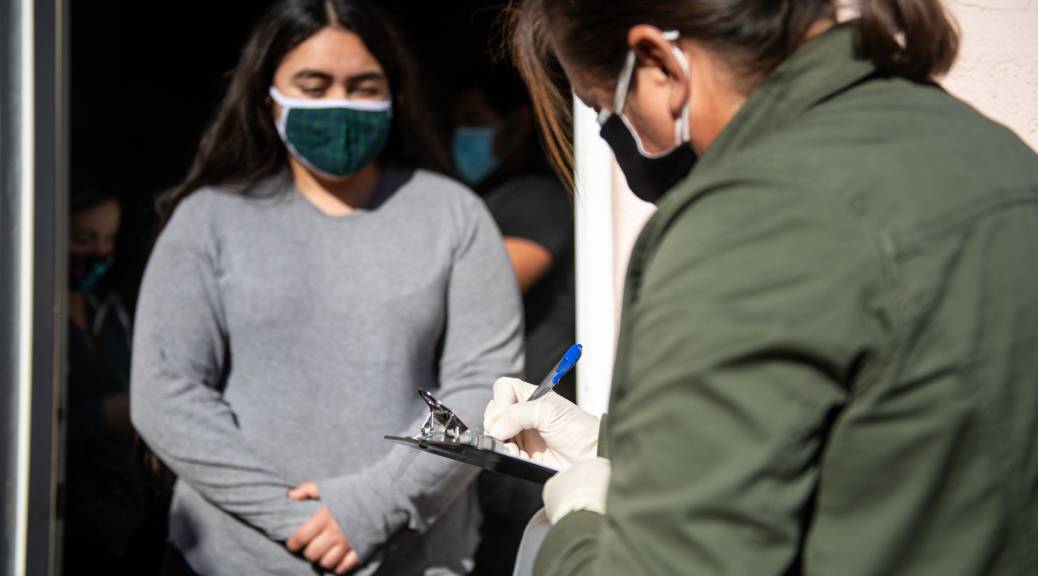

The process was easy enough: During a Sunday shift in late February, she walked from her workstation to an outdoor vaccine line. The whole process took less than 30 minutes, including the 15 minutes she sat in observation after her shot.

California has more than half a million farmworkers – and they appear to be eager to get vaccinated. Counties only recently started offering vaccinations to this hard-hit workforce, but agricultural workers are so far accepting the vaccine at high rates.