The morning after a violent mob stormed the U.S. Capitol, Principal Blain Watson was stressing.

“I was up all night thinking about the responsibility,” said the principal of academics at Alain LeRoy Locke College Preparatory Academy in Watts.

The morning after a violent mob stormed the U.S. Capitol, Principal Blain Watson was stressing.

“I was up all night thinking about the responsibility,” said the principal of academics at Alain LeRoy Locke College Preparatory Academy in Watts.

After the Jan. 6 insurrection, which disrupted Congress’s official electoral tally in favor of Joe Biden, educators around California had to decide how to address the attack with students. Some only touched lightly on the subject, others had full lessons prepared the following day, and many opted to avoid the subject altogether.

Watson went all in.

“A lot of us make the mistake of just saying, ‘All right, kids, this is what happened. Let's hear your thoughts,’ ” he said. “But we have to really be responsible about the messaging around race.”

Between COVID-19 and the examination of systemic racism after the killing of George Floyd, Watson knew his mostly Black and Latino students were already raw. Now, rioters, some with white supremacist ties, had carried the Confederate flag into the Capitol in the name of overturning a fair election, something they hoped to accomplish by a rejection of election results, based largely on fictional conspiracy theories about fraud in cities with large Black populations.

So if teachers were going to support their students, they’d need support, too.

“Educators need to be prepared for the range of emotions kids may be feeling — from sadness to rage,” Watson said.

Beyond helping students explore their emotions, he wanted to empower them to channel those feelings into designing a schoolwide response.

For 17-year-old Marveon Mabon, the student body president, the invitation was welcome; he’d been hungry to create a space for students to bring their full selves to the classroom.

“I feel like the schools expect us to just drop the hardship, drop the losses, drop the traumatic experience that we go through and just focus on school,” Mabon said.

Student Vice President Angelica Barrera, 17, jumped at the chance, too.

“I don't want to be old and know that when I saw events happening, I did nothing about it,” she said. “My main goal for this is to get students ready, to teach them how to respond when we see things like this happen, instead of ignoring it or letting it defeat us.”

In the days after the attack on the Capitol, Watson, Mabon and Barrera got together with teachers over Zoom to begin planning a series of virtual town halls, where the school could engage in deeper discussion about what happened.

“I started class with tears in my eyes. And I was like, how am I going to get through this?” history teacher Alette Kendrick told the group during the first meeting a couple days after the attack. “In these times where it feels like it's so important to be a good teacher, I've also felt like there's never been a harder time for me to be a good teacher.”

The conversation moved from how to handle their own emotions to the importance of teaching the history of resistance in Black and brown communities to the way the insurrection was resurfacing family trauma for recent immigrant students from Central America whose parents had fled civil war.

Kendrick called on colleagues to ground themselves in the history needed to give students proper context.

“We ourselves have to become versed and informed to be able to support our students in understanding this moment and having agency within it,” Kendrick said. “We've seen things very similar to this happen. And what that means is that we can also look to how people have been able to respond and survive this type of violence in the past.”

The group talked about connecting the current moment to Watts’ own history of civil unrest and how it shaped the community. In fact, their very school was built in response to the Watts uprising of 1965.

Eventually the group is hoping to bring community elders and local activists to speak to students as part of the town hall series. To pull something off before the inauguration, they started small. The afternoon before Biden was sworn in, they held their first event, a panel discussion with students and teachers.

“Our community is a community that we hear too often is underheard and underrepresented,” Mabon told the 60 or so students, parents and staff in the Zoom conference. “And this will be that platform to now represent and make sure our voices are heard.”

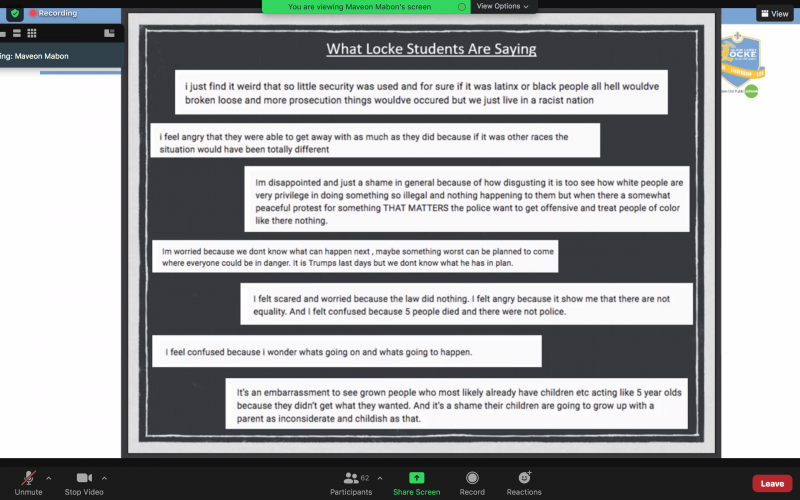

In the lead-up to the discussion, the school had surveyed students about the insurrection, and Mabon shared the results: Though 80% said they’d discussed the topic in class, nearly half said they were confused about the events.

The town hall provided a place for the student leaders to answer questions and share their own thoughts.

“What happened at that capital is an insult,” Barrera said. "It was horrible. I was in shock. And as young kids, we have to grow up with this.”

Teachers also got a chance to talk about what’s occurred in the past.

“We’ve seen it in our country before, and we’ve survived it before,” Kendrick said, describing the insurrection as part of a pattern of white supremacist violence throughout American history. “Most importantly, these things happen as a backlash, as a negative response to a lot of positive changes and progress that’s actually happening in our country.”

Mabon and Barrera described their own community activism, then called their classmates to action. “Get out there and get involved,” Mabon said. “Don't be scared.”

Principal Blain Watson closed by telling the student leaders how proud he was.

“One Locke, one love,” Watson said. “Let’s get ready for this inauguration tomorrow. Tomorrow's gonna be a day you'll never forget.”

After the attack in Washington, D.C., one of Watson’s biggest fears was that seeing Confederate flags flying in the Capitol, and police standing by and taking selfies, would cause students who already had reason to distrust the government to lose faith in their country altogether.

The next day, as Mabon watched a newly sworn-in President Biden address the nation, he said he was holding his breath, thinking, “Please, please, please do not cut the screen and say there was an emergency, there was a shooting!”

But seeing Kamala Harris on stage, he felt a sense of possibility.

“When I saw Barack Obama and Michelle Obama come out as a power couple, [and] the first Black senator who was there from Georgia — it was just so much hope and so much inspiration in that one frame,” Mabon said.

At least for now, this is the version of his country he’s choosing to believe in.

“This,” he said, “is the real America.”

To learn more about how we use your information, please read our privacy policy.