Los Angeles County will stop billing people millions of dollars a year for the costs of their incarceration in an effort to lighten the financial burden on former inmates.

The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously Tuesday to eliminate all criminal administrative fees over which the county has discretion after hearing testimony from dozens of formerly incarcerated residents.

The county is the fourth in California to eliminate the fees. If a bill introduced in the state Senate is approved, the rest of California could soon follow.

“Most of the people who have contact with the criminal justice system are already struggling to make ends meet,” said Supervisor Hilda Solis, who co-wrote the measure. “It’s most definitely not the purpose of the justice system to punish poor people for their poverty.”

Among the fees that Los Angeles will no longer collect are a monthly $155 charge for probation supervision, $769 for a pre-sentence report, $50 for alcohol testing and legal counsel fees that can reach hundreds of dollars, according to a November report from a coalition of criminal justice reform advocacy groups.

“It’s just never-ending. It’s a revolving door of fees and stipulations,” Cynthia Blake told the supervisors. A mother of seven, Blake said she was homeless when she was assessed more than $5,000 in probation fees nearly a decade ago. Unable to pay, she “ducked and dodged” the probation department, ultimately ending up in prison.

The vote followed a December report from the county’s Chief Executive Office finding that the county assessed an average of $121 million in fines and fees each year since 2014, but collected about $11.4 million annually, or 9%.

Including all fees, fines and restitution, Los Angeles still has over $1.8 billion in outstanding debt on the books, dating back 50 years. The measure doesn’t touch restitution or fees and fines required by state law, however.

The county’s 2019-2020 budget for public protection — which includes the Sheriff’s Department, which operates county jails, probation and the courts — is $8.9 billion.

Los Angeles follows the lead of San Francisco, Alameda and Contra Costa counties, which have passed similar measures in the past two years. More than 30% of California’s nearly 73,000 jailed inmates and 356,000 probationers reside in the four counties that have eliminated fees, according to data from the Board of State and Community Corrections and Chief Probation Officers of California. Another 127,000 inmates are in state prisons and 45,000 are on state-run parole.

The supervisors also resolved to write Gov. Gavin Newsom and legislators in support of Senate Bill 144, which would eliminate several of the most common and costly criminal administrative fees charged by counties and the state prison system.

“We are further hampering an already fragile family or community economically,” said state Sen. Holly Mitchell, a Los Angeles Democrat who authored the bill.

The bill is opposed by counties and law enforcement groups, which say that eliminating fees would leave gaping funding holes.

“One of the problems is that the Legislature passes laws that have to be paid for ... When they didn’t want to use general funds, they allowed it to be done as a fine or fee,” said Darby Kernan, deputy executive director of the California State Association of Counties. “That’s what holds the system together, and minus those dollars, the system will collapse.”

Kernan pointed to a 2016 state law that required people convicted of driving under the influence to install in their cars an interlock device — a breathalyzer that must be passed to turn on the ignition — and pay an administrative fee to cover the cost.

But Mitchell urged the governor to recognize that criminal fees are a “self-defeating, anemic source of revenue,” in a statement Tuesday.

“If LA can afford it, California can to,” Mitchell said.

Los Angeles’ move may bode well for Mitchell’s bill, if history is an indication. The county was a trendsetter when it stopped charging fees to parents for their kids’ time in the juvenile justice system in 2009. Three Bay Area counties followed, Mitchell introduced a bill to do so statewide and in 2018, California became the first state in the nation to abolish juvenile fees.

But that law didn’t do away with preexisting debt from the juvenile fees. While most counties, including Los Angeles, stopped collecting the old fees from parents, 22 counties haven’t.

Both the Los Angeles ordinance and Mitchell’s proposal make old administrative fees uncollectible.

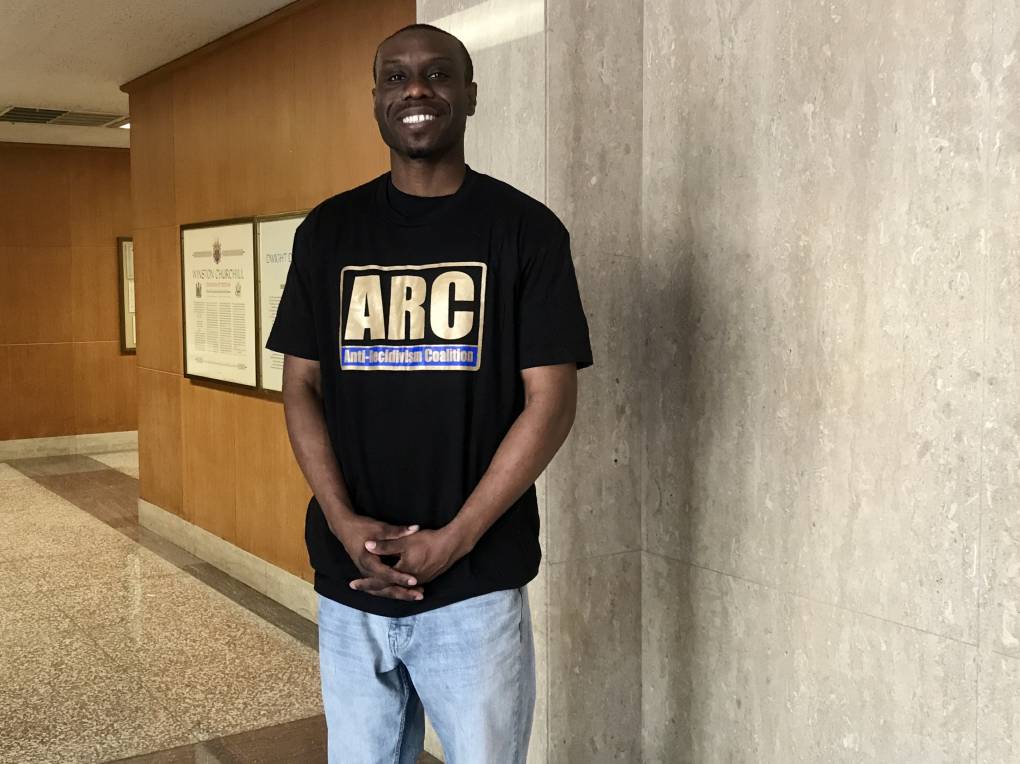

That could make a big difference for Marquies Nunez. When the 28 year old finished a 13-year sentence four months ago, he received a new bill for $1,000 from Los Angeles County. That was on top of the $12,000 he already owed in restitution fees, $2,000 of which he had paid off by working for 30 to 60 cents per hour while imprisoned.

“I was actually devastated and hurt ... knowing that I worked so hard while I was in jail to pay off my restitution and now here it is, I got bumped up an extra $1,000,” Nunez said.

After Los Angeles’ vote, Nunez is optimistic about spreading the wave of reform to the rest of the state.

"We’re going in the right direction. We got a good governor, we got good people outside here voting for these laws, good people in the Senate,” Nunez said. “We’ve got a bright future ahead of us.”

Jackie Botts is a reporter with CalMatters. This article is part of The California Divide, a collaboration among newsrooms examining income inequity and economic survival in California.