'We found high rates of emotional distress in these children.'[/pullquote]Studies of mothers in family detention centers show they had high levels of hopelessness and depression, says Torres.

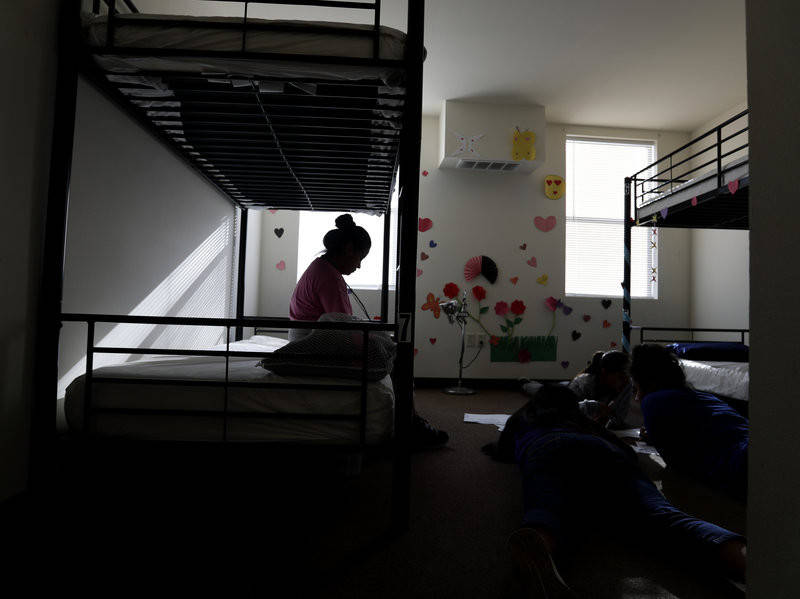

"They were unable to have a proper parent-child relationship within the detention center," she says.

Children and families in detention feel threatened by their environment, says Zayas: "It's not the normal experience of children to be living behind walls with barbed wires on them."

"There are prison guards who loom large, who are often gruff and not sensitive, because they are prison guards. They're not guardians," says Zayas.

Research shows that chronic stress and adversity affects the development of kids' brains.

"It affects regions of the brain and functions that have to do with cognition, intellectual process, with judgment, self-regulation, social skills," says Zayas. "And it really troubles me that there will be thousands and thousands of children who will be scarred for life."

Some children might bounce back once they're released from detention, he says, but many will need long-term mental health care to recover from their traumas.