The plan was possible because Long Beach uses a special measurement to analyze student test scores—something used by only eight California districts. Called a “growth model,” it’s become the subject of a raging debate over how California reports schools’ test scores to parents and the public.

At issue is whether the state will measure students’ performance over time, revealing which schools help students learn more from one year to the next. That would mean, for example, reporting how this year’s fifth graders compare to last year’s fourth graders at a given school. The current system instead measures how this year’s fourth graders compare to last year’s fourth graders, so it doesn’t reveal whether individual students are actually learning more.

Advocates for struggling students say measuring progress over time is key to closing the achievement gap that separates white, Asian-American and middle-class students from their black, Latino and low-income peers. For years, they’ve been lobbying state education officials to start measuring growth.

But after studying several ways growth could be measured, the state board of education delayed making a decision, saying the metric yielded volatile results that don’t necessarily show if achievement gaps are closing. Activists lined up at the board meeting this month to plead with the board to take action so that parents and educators can start seeing growth measures soon. But to no avail—the board voted simply to continue studying the idea.

“It’s starting to sound to me like a lot of excuse-making,” said Carrie Hahnel, deputy director of Education Trust West, a group that advocates for disadvantaged students. “They could have said ‘We need to refine this model but we are still going to vote to include a growth model.’ They could have made the policy commitment while they resolve the technical details.”

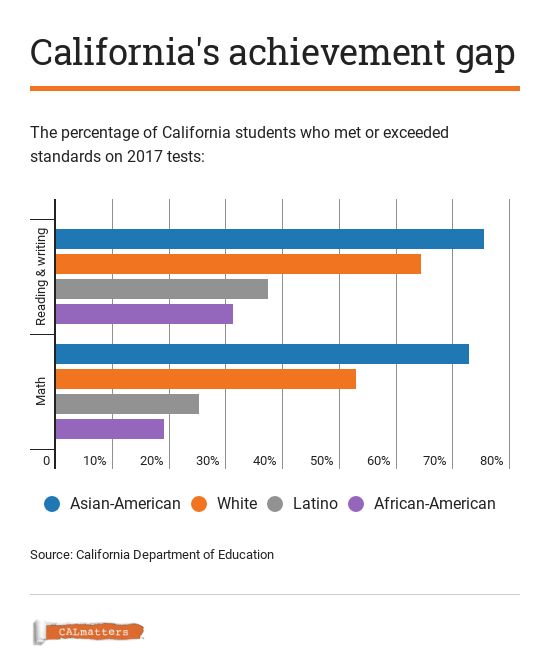

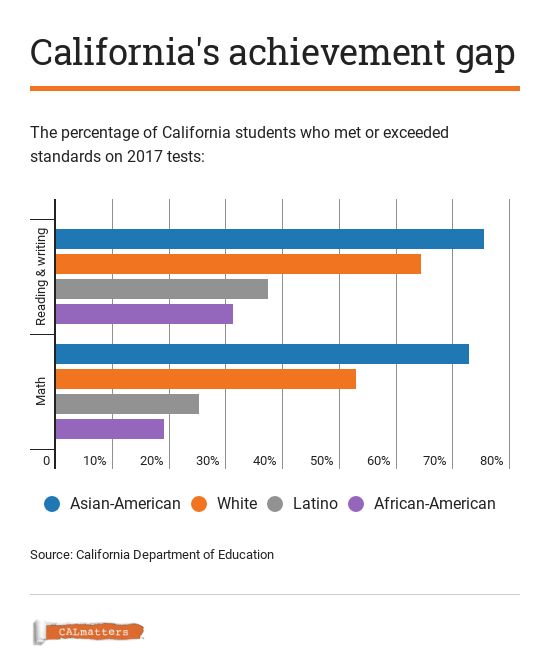

The delay has become another flashpoint in the years-long battle over how to narrow the achievement gap in California schools. Statewide test scores from last year show more than half of white and Asian-American students met or exceeded math standards, while the same was true for just 25 percent of Latino students and even fewer African-Americans. Reading and writing exams showed the same pattern. Though scores and testing regimes have changed, the overall trend in California has been similar for many years, through multiple superintendents, boards of education and pedagogical fads.

But the dispute also reflects an epic shift in how California is evaluating its schools—replacing a system based only on test scores with one that also measures factors like absenteeism, suspensions and graduation rates.

“This is what scares me a little bit about this conversation,” board of education member Sue Burr said at the recent meeting about the growth model. “For the last four or five years, we have made a concerted effort to move away from making decisions based solely on test scores. And I feel a sucking motion pulling us back in that direction.”

Advocates who want California to embrace a growth model point out that 40 other states already use some version of it. But the board president rebutted them, saying many of those states created a growth model as a way to evaluate teachers.

“There is an implication… that we are behind but maybe we are not,” Michael Kirst said. “Forty states did it but they had another reason.”

Linking test scores with teacher pay is a political non-starter in California. The teachers union staunchly opposes it and has a lot of influence on elected Democrats. The California Teachers Association has said its teachers must “lead the process” of developing a growth model for the state, and that it should not be used “for purposes of pay, promotion, sanction, or personnel evaluation of an individual teacher or groups of teachers.” The teachers union supported the board’s decision to delay action and keep looking for another way to create a growth model, spokeswoman Claudia Briggs said.

The eight districts in California using a growth model include Fresno, Garden Grove, Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, San Francisco and Santa Ana, plus Long Beach. They banded together in 2010 to improve teacher training and now share test score data that includes a formula for measuring growth.

But growth models are not all the same—they can be based on different mathematical formulas—and state education officials said the version those districts use is unlikely to work for the state as a whole.

It’s hard to predict whether the state will embrace a growth model at all, since the board of education is appointed by the governor, and Jerry Brown’s term will be over at the end of this year. But advocates who want it are not giving up. They’ve already begun thinking about how to leverage the issue next year—perhaps by lobbying the Legislature to get involved.

“It’s unlikely to happen under this governor,” Hahnel said. “But already we are looking to the next legislative session and that’s probably a valuable option.”