Six years ago, Gold was lured back to the L.A. Times, where he got his start after graduating from UCLA. He'd been writing for L.A. Weekly since 1984. His singular column on food began two years later. Even its title foreshadowed that he'd be different. He called it "Counter Intelligence."

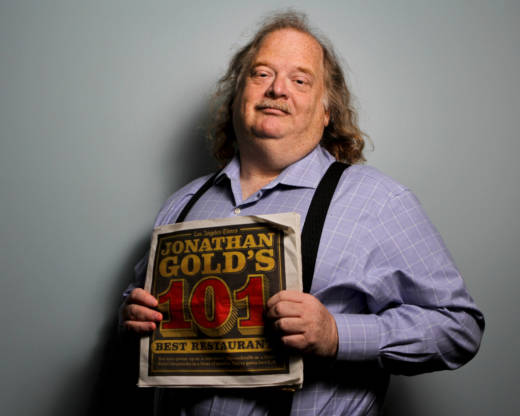

And it was in that role that his distinctive best restaurant list -- Jonathan Gold's 99 Essential L.A. Restaurants -- became a bible for foodies. When he moved to the L.A. Times he expanded the list by two and it became Jonathan Gold's 101 Best Restaurants.

He knew he held tremendous power to make, or break, an establishment. A negative review from him had the potential to put many low-wage people out of work.

Even when he didn't like a place, he tried to understand why other people might. In one case, he returned to a crowded Taiwanese restaurant 16 or 17 times to see if the unfamiliar flavors grew on him.

"I realized that the food wasn't like this, because they were bad cooks. My ideas of it were because of my cultural relativism," he told NPR's Renee Montagne in 2016. "It wasn't food that I was used to eating."

His ultimate ruling? He just didn't crave the food. And that was OK because he came to understand it.

"And I think in a lot of ways that's more valuable than if I'd just gone in there and made cheap jokes at the expense of the food," he said, "or I'd given it a bad review because I thought it was bad."

Reading his reviews was like listening to friends talk about the best meals they'd ever eaten.

Here's an excerpt from one of the stories that made him the first, and only, food critic to earn print journalism's highest honor, a Pulitzer Prize, in 2007:

"When it is 109 degrees in Pasadena, when the live oaks droop and the front range of the San Gabriels burns with a terrible heat, there is no better place to be in the city than the shaded courtyard of the Pacific Asia Museum, among the Japanese statues and the swimming koi, the muscular Myron Hunt architecture, and the frail cart that houses Bulgarini Gelato, whose pistachio is fragrant as a lyric poem, whose lemon tames the sun, whose peach-moscato sorbetto is even more delicious than a chilled Bellini, even more delicious than a chilled Bellini made from a peach you have plucked from your own tree."

Gold was 57. He is survived by his wife Laurie Ochoa, an editor at the L.A. Times, and a son and daughter.