“Under this system, districts can escape notice or attention simply by shining in categories that are less than academic and whose outcomes they control,” said Chad Aldeman, an education policy expert whose Boston-based nonprofit group flagged this problem in a recent report on California’s school accountability system.

Raising similar concerns, the federal government recently notified the state that California’s school accountability system might be out of compliance with federal education law, in part because of its diminished focus on academics.

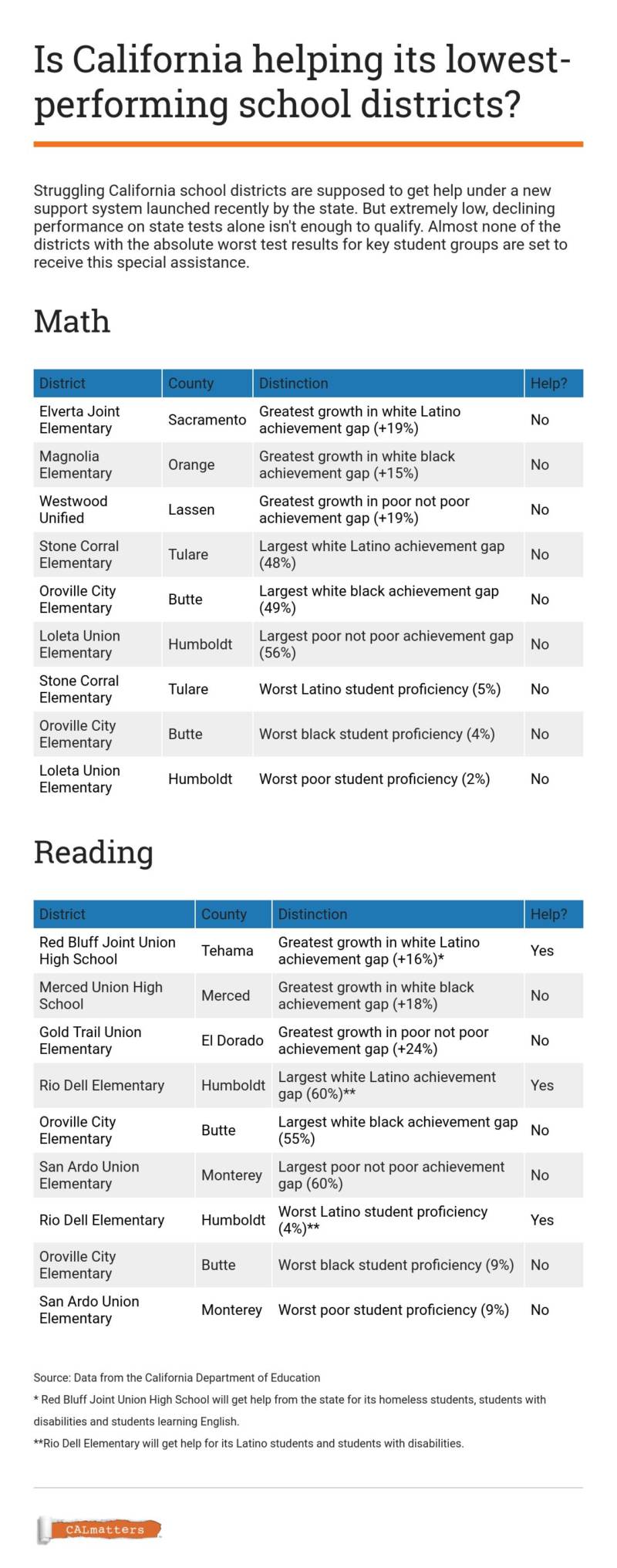

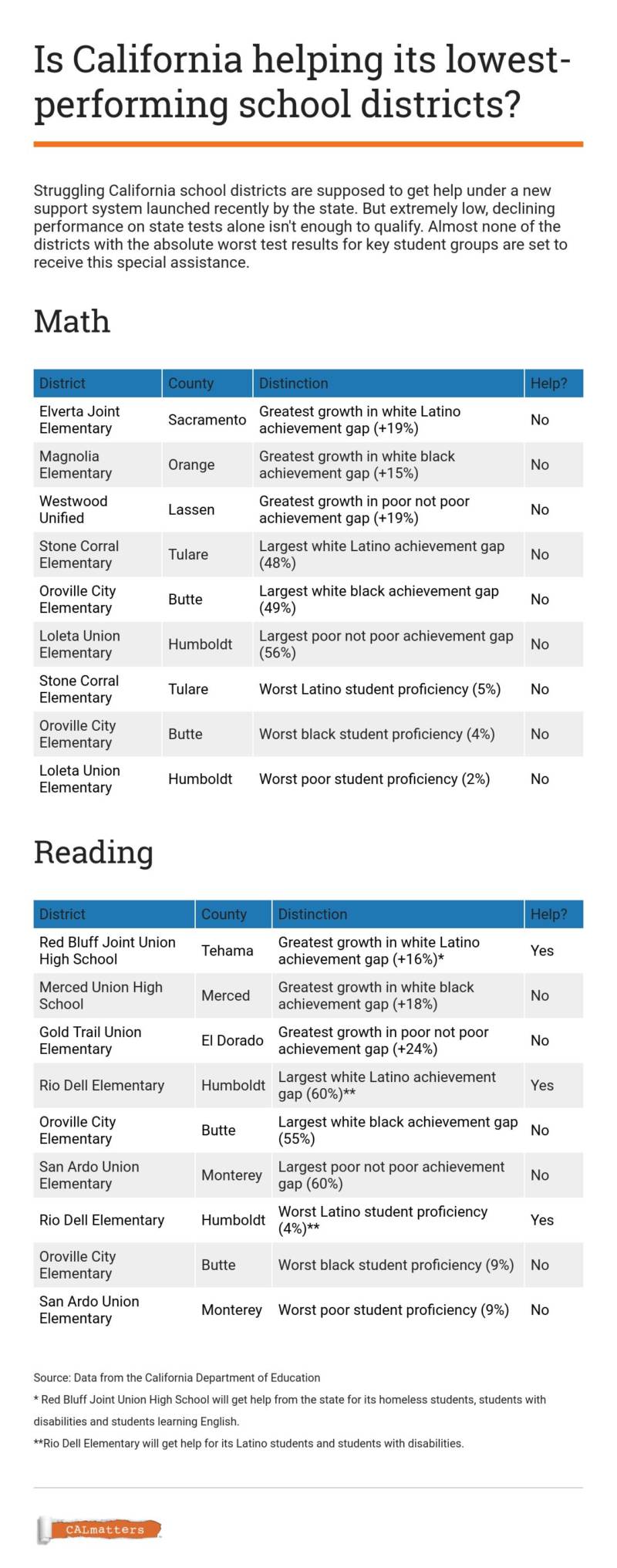

The state created the color-coded dashboard system to identify its lowest-performing school districts. To determine them, the state isolates about a dozen student subgroups (such as Latino students or poor students) and rates them in four categories: academic test performance, suspension rate, graduation rate and success teaching English to students who can’t speak the language.

Earning red ratings in any two categories triggers special state help for the underperforming subgroups in that school system.

But numerous subgroups of students with some of the states’ worst test scores didn’t make the cut. About a third of California’s roughly 1,000 school districts have at least one low-performing subgroup that’s not set to get any extra assistance.

Districts that do get flagged qualify for increasing levels of state intervention—starting with a data analysis conducted by a county office of education that’s aimed at understanding the root causes of poor performance, and escalating up to possible state takeover if a district fails to improve. The dashboard does not explicitly record the size of the achievement gap—even though state officials call narrowing it a top goal.

Among examples that illustrate the support system’s shortcomings:

- In Santa Ana, one of the state’s largest school districts, only 4 percent of students learning English passed the state test in math and just 2 percent passed reading, levels of performance labeled red and orange on the dashboard. Yet Santa Ana didn’t make the cut. That’s because English learners there earned better than red in all the other key categories.

- Stockton’s test scores show that it has eight extremely low-performing student subgroups—more deficient subgroups than any other district in the state. But only one, disabled students, are set to get state assistance.

- In San Francisco, fewer than one in five black students passed state tests in math and reading. But because black students’ suspension and graduation rates won orange and yellow ratings, the district doesn’t qualify for outside help aimed at them.

In fact, almost none of the districts with the state’s absolute worst test results for poor and minority students and the largest academic achievement gaps will receive special assistance.

State Board of Education President Michael Kirst and state Superintendent for Public Instruction Tom Torlakson declined CALmatters’ requests for interviews. But in a joint response to our questions, their spokespeople said the state’s criteria for special assistance and the list of districts set to get it reflect California’s deliberate move away from accountability driven by test scores alone.

“That said, test scores are important,” Janet Weeks and Bill Ainsworth wrote. “If a subgroup has very low test scores, they have met half the requirement for assistance.”

Separately, the officials released a statement saying that while they don’t agree with all of the U.S. Education Department’s findings, they welcome the feedback.

Two-thirds of the districts that do qualify for extra help under the dashboard system landed on the state’s list because of lackluster achievement among their students with disabilities. Not only did the students’ test scores earn a red rating, but their suspension or graduation rate did, too. That means those students’ needs are the greatest in the eyes of the state, Weeks and Ainsworth said.

“This is precisely how the system was designed to work,” they wrote. “The dashboard was intended to bring to light inequities and highlight the most glaring gaps in California’s educational system.”

Some observers see things differently. The number of districts on track to get help may be limited by the state’s capacity to lend support, said Carrie Hahnel, deputy director of research and policy at Education Trust–West, a nonprofit advocacy organization committed to closing the achievement gap.

“An ideal system would send support to anyone that’s severely struggling with academics,” Hahnel said. “But the state has limited resources. It has to triage.”

So, if California used a different, broader formula to determine which districts to assist—one that offered support to all of the ones with extremely low-performing student subgroups—would the state have the resources to provide that help?

Weeks and Ainsworth said this:

“The goal of the system is to increase and build capacity statewide so all districts that need support can get it.”

Stockton Unified got flagged for support because the dashboard gave the district’s disabled students several red ratings. Still, seven other student subgroups with bottom-of-the-barrel test scores will escape state scrutiny because they rated better than red in the other categories.

Acting Superintendent Dan Wright said he grew concerned about his disadvantaged students’ achievement long before the state released the dashboard. And he doesn’t need an outside consultant to tell him that high rates of teacher turnover in his highest poverty schools are impacting poor kids’ learning. Still, he’s hoping that whatever ideas the state suggests to help his disabled students can help their peers, too.

https://infogram.com/students-help-no-help-1h706e05lpjj25y

“To be honest, I’m not sure if this system is right or wrong,” Wright said. “What I can tell you is districts that care will own their numbers, drill down and do something about it—whether they get extra help from the state or not.”

The special assistance that districts like Stockton qualify for will come from their county offices of education, or another state-approved provider.

The Kern County Office of Education is gearing up to assist 15 of its roughly 50 school districts, a greater workload than that of all but two other counties.

That work will begin with a data-driven analysis, said Lisa Gilbert, the county’s assistant superintendent of instructional services. For example, if a school district needs to boost its attendance, the county will aim to help the district get to the bottom of its chronic absenteeism.

“This process is uncomfortable. It is not fun,” said Gilbert, who noted that districts on track for extra help can choose to opt out—and that the county may be able to support a few additional districts that didn’t qualify. “It requires looking in the mirror, not out the window, and being honest about what you’re doing and not doing to help kids.”

Gilbert has high hopes for the school systems she’ll be assisting. But several academic experts said they’re dubious about the support system’s potential.

“Being on this list will only yield marginal benefit,” said David Plank, who directs Policy Analysis for California Education, a research center at Stanford University. “No one at the state has proven that they know what to do or how to help.”

CALmatters staff reporter Matt Levin compiled and helped analyze data for this story.

You can download some of the underlying data we used for this story here.