At school, Pharroh is in a special education class with a group of other kids that all have different needs. Consistency is important for a lot of special ed students, so in theory, the kids get the same teacher for two years in a row. But Mosley-Katakanga says there have been problems, even in kindergarten.

"We started the first day of school with a substitute teacher," Mosley-Katakanga remembers. "I think we went through about three sub teachers, until they solidified a teacher they considered to be qualified who had some special ed experience."

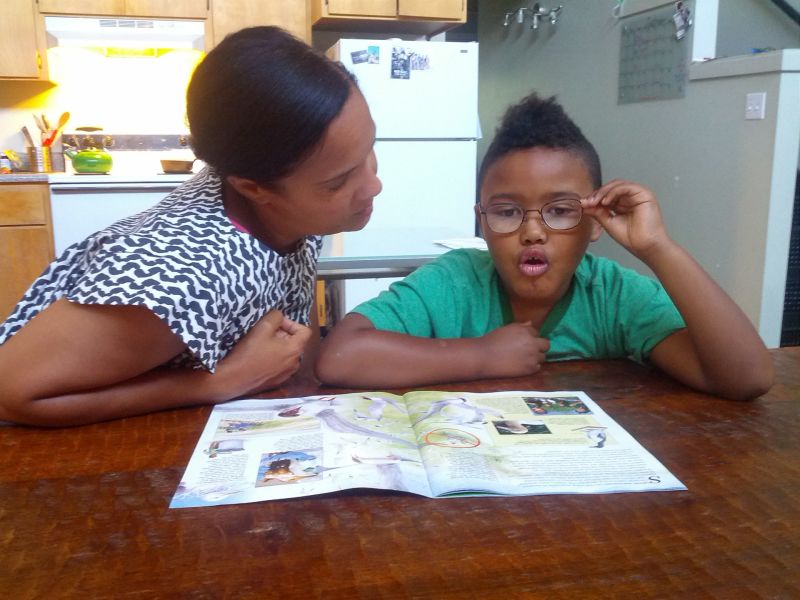

Mosley-Katakanga doesn’t want to name her son’s elementary school in Oakland to protect teachers’ privacy. Pharroh’s first year was so difficult that his mom asked for him to repeat kindergarten. She says he had a great teacher for the next two years. But now he’s moved on to a second- and third-grade classroom. Last year, that class had substitutes all year.

"This is the same group that had the sub half the year in kindergarten/first grade. The whole group was double whammied with subs in their few years of education," says Mosley-Katakanga.

When substitutes don't have the right special education credential, they can't be in the classroom for more than 30 days, so these students sometimes end up with a different teacher every month. Substitutes can be hard for any student, but especially for kids with special needs.

"There’s no learning! The reality is when they’re with a substitute, they're just not getting the same quality of education," says Ismael Armendariz, a special education teacher at Edna Brewer Middle School.

Armendariz says the turnover makes it harder for teachers like him to do their jobs. This year, he says a special ed teacher at Edna Brewer resigned the Friday before school started. For the first few days, he and another teacher took on a half-dozen more students each in their morning language arts classes. In addition, they were writing lesson plans for the substitute. Armendariz says that makes it hard to make the one-on-one connections and develop the rigorous curriculum that are crucial for these students.

"Our students are the highest-need students and most at risk," says Armendariz. "Our students are the ones who are most likely to go to jail, most likely to have mental health issues and not get services."

The district is well aware of the problem. Kara Oettinger is the executive officer for Oakland Unified’s special education programs, known as Programs for Exceptional Children. She says the district is prioritizing keeping the special education teachers they do have. They’re trying to provide more professional development around special education for all teachers, and for the first time last year, they began providing coaching by and for special education teachers.

"Previous to that, special ed teachers didn’t get support or they got support from a teacher who doesn’t know anything about special education," says Oettinger.

She says they’re also training special education aides to become teachers. It’s part of a districtwide strategy to grow their own.

Mosley-Katakanga hopes the district provides enough support for her son's new second-grade teacher. If he doesn't get that support, she's worried he could get so overwhelmed that he might end up leaving, too. She doesn't know where to go to find a more stable special education workforce.