And so I asked the governor: How did that deal square with his often proclaimed love for the principle of subsidiarity -- the Catholic teaching that the most local, least centralized government should make most decisions?

Brown paused before he answered.

"The rule is subsidiarity," agreed the governor. "That particular provision appears to be an exception."

That apparent comfort with his conflicting decisions has been one of the hallmarks of Brown's return in governing California. While sometimes he's held fast and just shrugs it off, other times the governor has come around and changed his mind.

In this instance, he said there's some "language in the budget" that agrees to take a closer look at the issue of the state dictating what local school districts do with their savings accounts. And when I asked him to respond to criticism that he'd done it only to mollify Prop. 2 concerns voiced by teachers unions?

"We did what we had to do," said Brown.

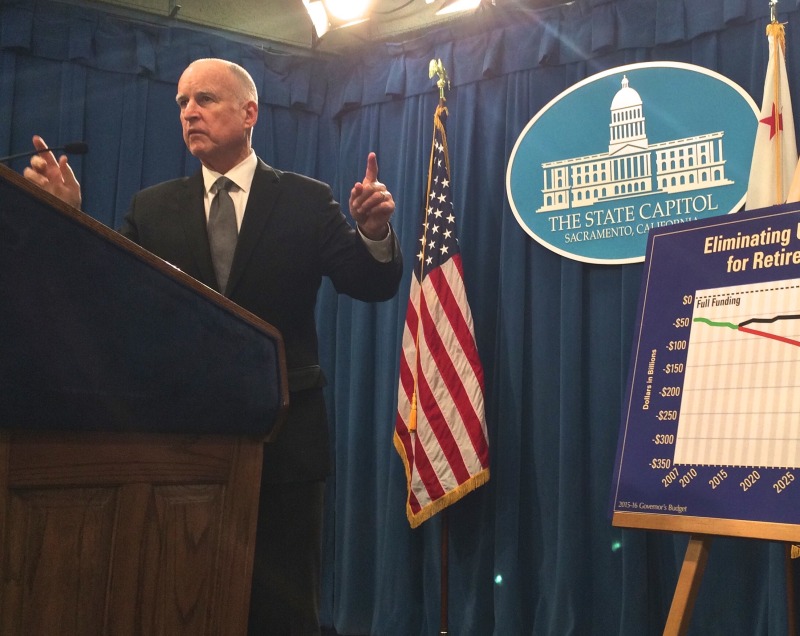

The governor's new budget offers several new places where his public stances may be tested against the realities of political horse trading.

Legislative Democrats will no doubt focus on the lack of sustained growth in funding social "safety net" programs. "The devastating budget cuts from years past have left many of the neediest Californians -- working families, students, children, the disabled and elderly -- without critical assistance," said state Sen. Mark Leno (D-San Francisco) in a written statement.

And he's not alone, with others suggesting Brown's approach to poverty has been too timid. In response, the governor has countered by pointing to the expansion of Medi-Cal by 4.3 million people over three fiscal years, and by his new budget proposal to shift money into adult education and career tech.

"There's always someone in need," Brown told reporters on Friday. "And we [California] are doing more than most."

The governor may also have to win over his traditional friends in public employee unions when it comes to a proposal to asking workers to split the cost of putting money aside for their health care coverage during retirement -- a major long-term liability. But his budget also proposes $560 million in salary and benefits increases for state workers, a sign that there's a deal to be made if union leaders will take it.

And there were other places in this proposed budget where Brown seemed to weave back and forth between conflicting ideas. He's a major advocate of more electric vehicles, and doubled down on that commitment in Monday's State of the State speech. But then his budget notes a serious lack of dollars for highway repairs and replacements -- and admits that the "consequence" of his clean vehicle campaign is less fuel excise tax dollars, which ... wait for it ... pay for those road repairs.

Unlike other governors, who may deny any inconsistency even when it's patently obvious, Brown seems to have made peace with it all. The larger question is how other players in the annual budget process will see those inconsistencies, and whether they create room for collaboration rather than confrontation.