For two decades, New York City’s small high schools stood out as one of the nation’s most ambitious — and controversial — urban education reforms. Now, a long-term study provides a clearer picture of their successes and disappointments.

In the early 2000s, under former Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the city closed dozens of large high schools with high dropout rates in low-income neighborhoods and, with $150 million from the Gates Foundation, replaced them with smaller ones, often located in the same buildings. Admission to more than 120 of the most popular new small schools was determined by lottery, creating the kind of random assignment researchers prize. (That represented the vast majority of the city’s 140 new small schools.) MDRC, a nonprofit research organization, followed four cohorts of students from the classes of 2009 through 2012 for six years after high school. (Disclosure: The MDRC analysis was funded by the Gates and Spencer foundations, which are among the many funders of The Hechinger Report.)

The early gains were substantial. Two-thirds of students entered high school below grade level in reading or math. Yet 76 percent of students admitted to small schools graduated, compared with 68 percent of those who lost the lottery — an 8 percentage point increase. Because more students finished in four years, the schools were cheaper on a per-graduate basis, MDRC found, even though they cost more per student and required more administrators overall.

College enrollment rose sharply as well. Fifty-three percent of small-school students enrolled in postsecondary education after high school, compared with 43 percent of the comparison group — a nearly 10 percentage point difference. Most attended a college within the City University of New York system.

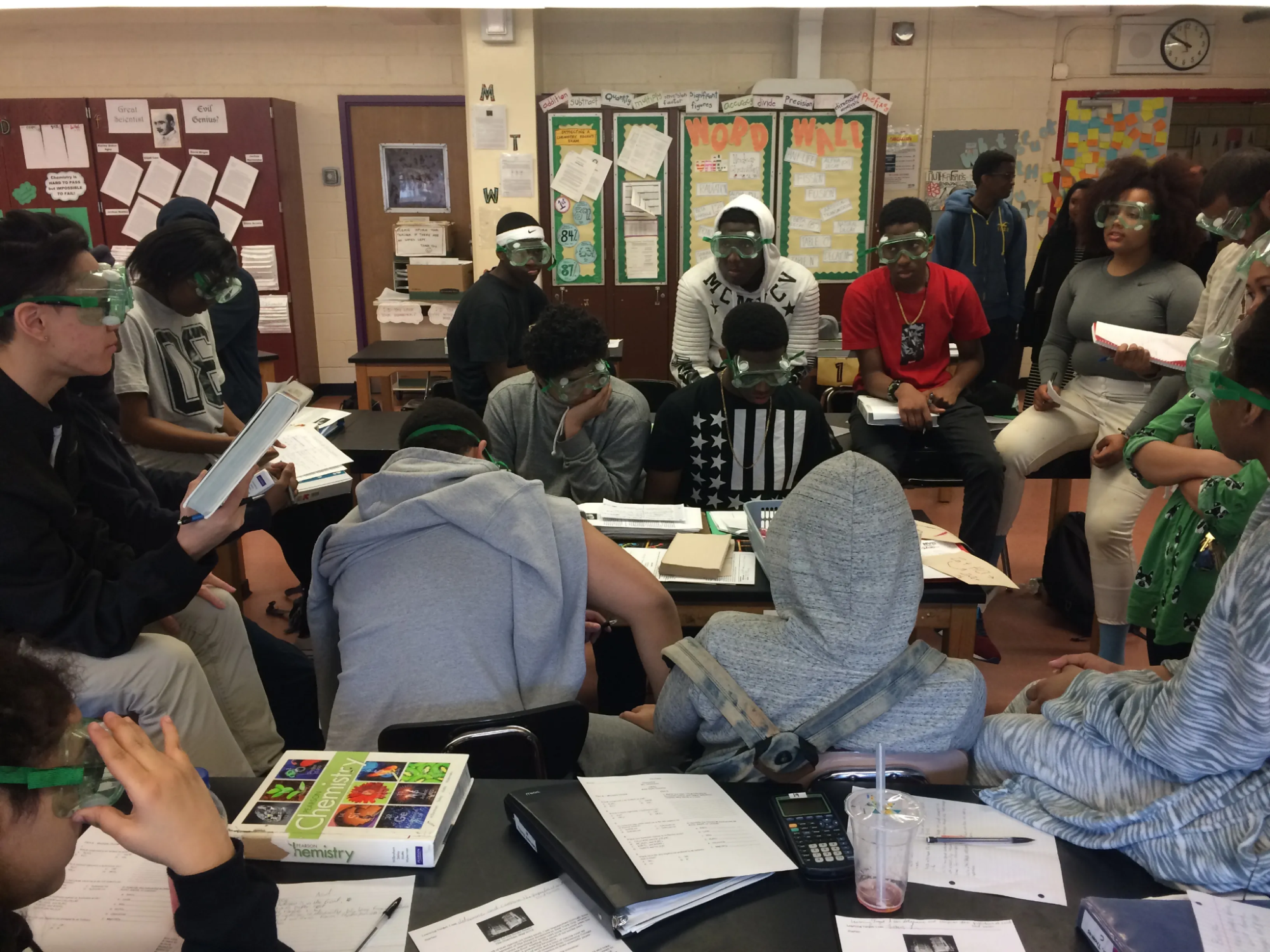

Small schools enrolled roughly 100 students per grade, creating tighter communities where teachers and students were more likely to know one another. Rebecca Unterman, the MDRC researcher who led the study, said the relationships formed in these environments may help explain the graduation and college-going gains. Many schools also built advisory systems in which teachers met regularly with the same students to guide them through academic and emotional challenges and the college process.