In the fall of 1918, Edward Kidder Graham, the president of the University of North Carolina, tried to reassure anxious parents. The Spanish flu was spreading rapidly, but Graham insisted the university was doing all it could to keep students safe. Weeks later, Graham himself contracted the virus and died. His successor, Marvin Hendrix Stacy, promptly succumbed to the epidemic two months later.

Many universities endured similar chaos during the Spanish flu, as I learned from reading a chapter in a forthcoming book on higher education, “From Upheaval to Action: What Works in Changing Higher Ed,” by sociologist and Brandeis University President Arthur Levine and University of Pennsylvania administrator Scott Van Pelt. (Disclosure: Levine was the president of Teachers College, Columbia University from 1994 to 2006, during which he launched The Hechinger Institute, the precursor to The Hechinger Report.)

But what really struck me was how many colleges’ experiences resembled those of the Covid-19 era.

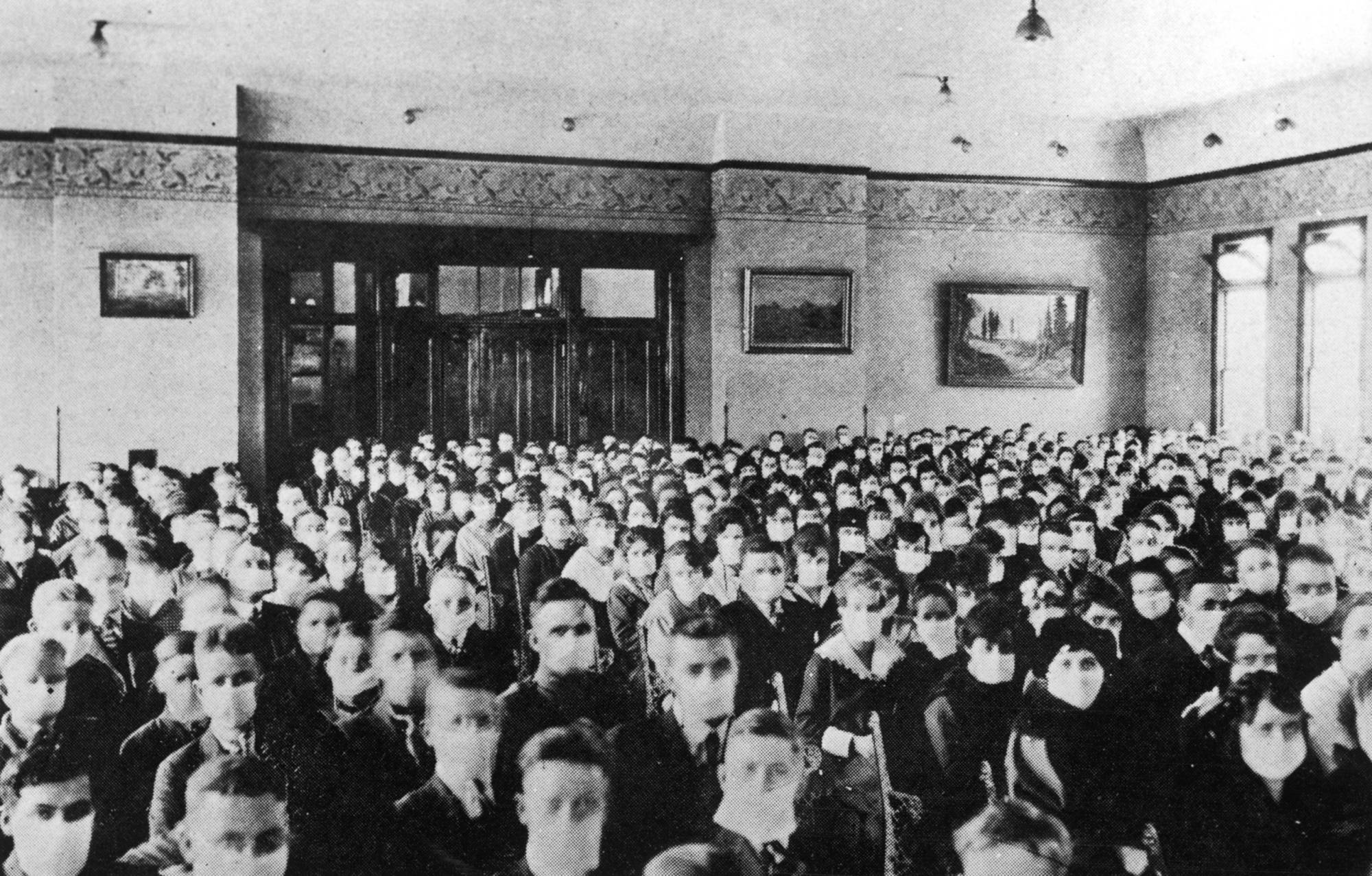

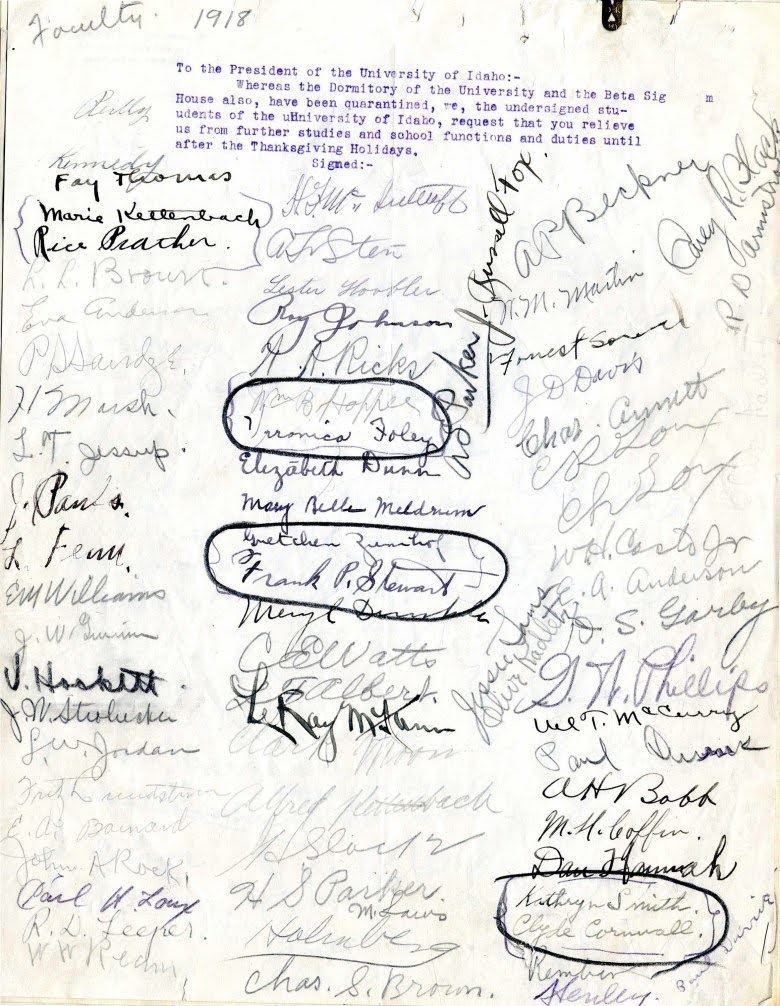

During the 1918 pandemic, Harvard canceled lectures with more than 50 students. Yale shut down its campus after partial measures failed to contain the spread. Many urban colleges closed temporarily. Orientations, commencements and large public gatherings were canceled or postponed. At Iowa State University, gymnasiums were converted into makeshift hospitals as cases surged. At the University of Michigan, dormitories transformed into quarantine facilities after infirmaries overflowed.

And then came a second wave — deadlier than the first.

The Spanish flu ultimately killed about 675,000 Americans at a time when the U.S. population was roughly 100 million — nearly twice the proportional death rate of Covid-19, which has claimed about 1.2 million lives in a country more than three times as large. Unlike Covid, the Spanish flu struck hardest at young adults in their 20s and 30s, the very ages colleges relied on to fill their classrooms and new faculty seats. Yet, Levine argues, higher education never managed to help that generation recover — academically, socially or psychologically.