Social media would seem a logical culprit for the rise in misery. Smartphones had just become ubiquitous around that time, and critics like social psychologist Jonathan Haidt have argued that they’ve been rewiring adolescent brains for the worse.

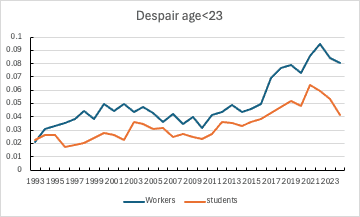

But when Blanchflower dug into the data, the smartphone story provided only a partial explanation. If social media were the main driver, you’d expect misery to rise among all young people at roughly the same rate. And while it’s true that ill-being increased among all young adults, Blanchflower discovered that the decline in well-being was concentrated among those young adults who were working, especially females under 25. College students and others not working still showed something close to the old happiness curve, even if the left corner wasn’t quite as upturned.

That raises a puzzling question: Why are young workers so unhappy?

They’re not having trouble getting a job. Employment rates for 16- to 24-year-olds have risen since 2010. Their hours have increased. Their relative wages have also risen. Blanchflower analyzed decades of U.S. survey data on mental health and linked it to employment outcomes. His analysis appeared in a working paper, not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal, but circulated by the National Bureau of Economic Research in January 2026.

This data shows that the rise in ill-being and fall in well-being are especially large for the youngest workers aged 18-22 over the last decade. And it confirms that non-workers this age, namely college students, aren’t as miserable. They’re still relatively happy. This diverging pattern was true for the U.S. as a whole and in all 50 states between 2020 and 2025. What’s particularly new, according to Blanchflower, is the sharp increase in despair and misery among young workers. He created this chart for me.

Despair is also sharply stratified by education: High school dropouts fare far worse than college graduates, even those of the same age.

But back to why. Blanchflower notes that job satisfaction among the young has fallen. A Conference Board survey shows a persistent gap between younger and older workers. In 2025, job satisfaction was 72 percent among workers aged 55 and over and just 57 percent among those aged 18 to 24. Across multiple dimensions, young workers rate their jobs as lower quality than older workers do, and report greater difficulty with job stability and making ends meet.

One interpretation is that young people increasingly have what anthropologist David Graeber memorably called “bullshit jobs” — work that feels pointless, insecure and disconnected from any sense of purpose. There’s no direct proof of that, but other researchers have argued that young workers have borne the brunt of gig work, declining bargaining power, and vanishing career ladders. Fears of being replaced by AI are also strongest among the young.

Previous generations also often landed boring first jobs and worried about financial security. But expectations for work may have changed for members of Gen Z. Since around 2012, the share of young people who say they expect their chosen work to be “extremely satisfying” has fallen from about 40 percent to closer to 20 percent. If work is no longer expected to deliver meaning or identity, its psychological payoff may be lower.

Another theory is that the mental health of today’s young workers began deteriorating when they were still in high school. That damage carried into adulthood, making the transition from school to work harder — especially for those without college credentials.

“The youngest workers, especially those without any college, are hardest hit, and we don’t know why,” Blanchflower concludes in his paper.

Blanchflower’s study is a warning that something fundamental has gone wrong as young people enter the workforce. Policymakers need to keep this in mind as they create more pathways to good jobs that don’t require college.

This story about young adult misery was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Proof Points and other Hechinger newsletters.