The next phase of the app will drop the camera analytics, and instead will use wearables like a Fitbit or Jawbone to send data in real time to a personal trainer, according to Bob Summers, CEO of Fitnet. There would be an actual person watching me (and likely hundreds of others), advising each of us how to get the best stretch.

Fitnet's algorithm is intended to help personal trainers determine who needs help at that moment by processing participants' exercise data simultaneously.

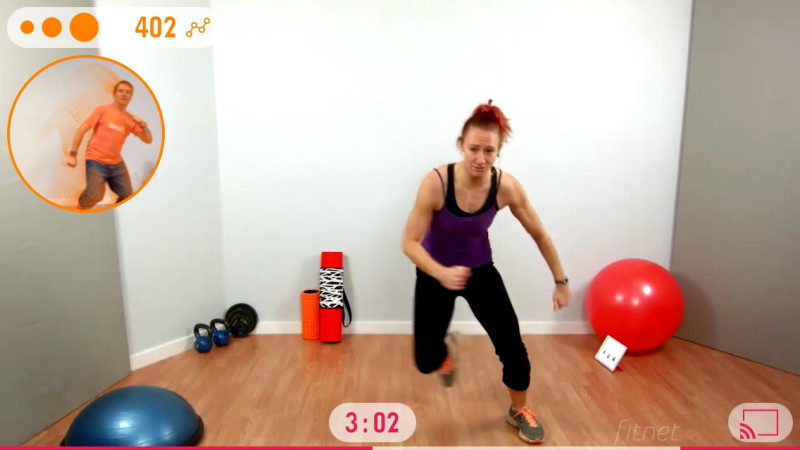

The real-time feedback to exercisers will give someone using the app an experience that feels more like an in-person session with a coach, says Joe Barnhart, a master trainer with the National Association for Fitness Certification. "When you're one-on-one with a client, it needs to be interactive," he says.

For the low price of "free," Fitnet will certainly beat the average hourly rate trainers charge, which can range from $45 to $200 per hour, according to Barnhart. (Eventually, the developers hope the app will make money through extras — like offering users the chance to take part in a social fitness challenge for $1.99 per month.)

Fitnet is partially funded by the National Science Foundation, which has a project called GENI that explores innovative applications. GENI is a nationwide gigabit network hosted by computer researchers — essentially a giant cloud computing network, kind of like Amazon or Google, which researchers can use to develop applications that need superfast Internet speeds. GENI offers "Internet 2" with speeds 40 to 100 times faster than current broadband.

Fitnet is being used to test whether real-time interaction is possible on a faster, next-generation Internet. It's a lot more complicated than a group video chat, explains Summers, and it requires an infrastructure like GENI's to test.

"We don't appear to be very aggressive in this country about providing bandwidth to users at an affordable price, and I think this is holding us back from being able to develop these kinds of applications," says Mark Gardner, a network research manager at Virginia Tech and one of Fitnet's research partners on the NSF grant.

But there are pockets of the country with superfast Internet — like Kansas City, Missouri, which was involved in the rollout of Google Fiber — that give broadband enthusiasts hope. Summers is optimistic that a real-time streaming trainer — with all of the buff, but none of the buffering — will be available in three to five years.

"It seems pretty clear that our future is more Internet and faster Internet," Summers says. "We feel health and fitness will drive the demand."

Copyright 2015 NPR. To see more, visit http://www.npr.org/.9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))