But to skeptics, the trial was laden with confounding details that make it impossible to draw conclusions.

“These results are a mess,” wrote Baird biotech analyst Brian Skorney. “Not so much that they indicate an outright failure of the [amyloid] hypothesis, but they don’t really say anything informative at all.”

In the trial, every single tested dose had a significant effect on plaques as measured by a brain scan, and the more BAN2401 patients got, the less amyloid they had after 18 months. But looking at cognition, only the highest tested dose was significantly better than placebo at slowing down mental decline. And some of the patients who received lower doses actually declined faster than those who received no treatment at all.

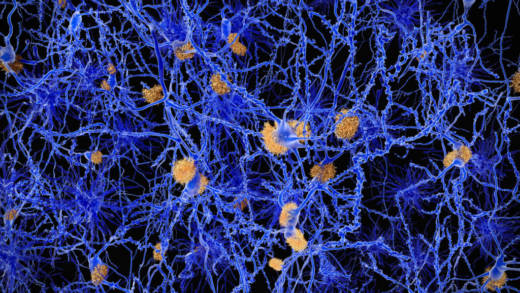

If amyloid really is the driving factor behind Alzheimer’s, why didn’t each incremental reduction in plaques lead to a corresponding improvement in cognition?

Dr. Al Sandrock, Biogen’s chief scientific officer, said there is likely a threshold of amyloid reduction that must be reached before patients actually benefit. The low doses, despite their effect on plaques, might not have hit that threshold, Sandrock said, thus accounting for their poor performance on cognitive decline.

The divergence in the two curves is what gives Dr. Reisa Sperling, who was overall encouraged by the results, “the most pause.” But Sperling, director Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, noted that some of the study’s arms had small numbers of patients, making it difficult to draw conclusions. She said while there is a biological argument that could underpin the threshold hypothesis, she wanted to see more data from a larger trial with a more traditional design.

Even if Sandrock’s theory holds up, what happened to BAN2401 is not a new phenomenon. This year a drug from Merck, meant to shut off the production of plaques by blocking an enzyme called BACE, was successful in reducing amyloid but fared so dismally on cognitive measures that researchers terminated the trial early. A second BACE drug, from Biogen and Eisai, had similar results in miniature, hitting the mark on plaque reduction in a Phase 2 trial but failing to significantly outperform placebo on cognition.

The underlying issue, according Dr. Lon Schneider, director of the California Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the University of Southern California, is that “the plaques are not the target — those are biomarkers.”

“A target is something that, as a result of hitting it, there will be change downstream in behavior, cognition, and illness course,” Schneider said. “So, yeah we’re knocking down amyloid, but so far we’re not changing behavior much.”

Even BAN2401’s saving grace — that its highest dose appeared to both reduce amyloid and improve patient’s clinical results — has come under scrutiny.

In the BAN2401 trial, about 70 percent of patients getting placebo had a genetic mutation that triples the risk of Alzheimer’s. But in the high-dose BAN2401 group, just 30 percent of patients had the mutation, called APOE4.

That could explain why BAN2401 seemed to outperform a saline injection in the high-dose group, skeptics say, as past trials suggest that APOE4 carriers have more rapidly progressing Alzheimer’s than patients without the mutation.

And it could mean that the drug’s seeming promise is a mirage.

Dr. Paul Aisen, who runs the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California, said the discrepancy “does create a potential bias.” But in trials where patients are confirmed to have amyloid in their brains at the outset, as was the case with BAN2401, “the impact of [APOE4] on progression is modest,” Aisen wrote in an email. “I don’t think this accounts for the apparent slowing of cognitive decline in the high-dose arm.”

Sperling agreed that she did not think the arms’ different populations skewed the data, in part because the group that received the second highest dose of the drug had a larger share of APOE4 carriers and saw results that were similar — though not as substantial — as the high dose group.

“It’s a similar pattern,” she said. “For me that partially mitigates that concern.”

Biogen and Eisai have promised to dig into the data and parse out the effect APOE4 had on whether patients responded to BAN2401, but those results likely won’t be ready for months.

In the meantime, companies are still queueing up to take cracks at amyloid.

Eli Lilly, which has spent billions on failed Alzheimer’s drugs in recent years, has designed a trial that will test the amyloid hypothesis “in the most definitive way possible,” said Mark Mintun, the company’s vice president of neurodegeneration.

The plan is to take a BACE inhibitor and pair it with an injected treatment that targets amyloid already in the brain. That should address the two major concerns with each approach, Mintun said: BACE inhibitors prevent amyloid but don’t address plaques that already exist, while amyloid-targeting therapies don’t stem the flow of new toxic clumps.

“I equate it to going down to your basement and finding three feet of water and there’s been a slow drip for four weeks,” Mintun said. “You can turn off the spigot, but it won’t feel like you’ve made much progress, so you’ve got to pump it out, too.”

That study is enrolling 375 patients into three groups, planning to study whether the combination can improve cognition compared with placebo over 18 months.

Andrew Joseph contributed reporting.