This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Scott Shafer: This is Forum. I’m Scott Shafer, in this hour for Mina Kim.

Each year, tens or even hundreds of thousands of animals—from dogs and cats to mice, rabbits, and monkeys—are used in research by scientists looking for cures, treatments, and vaccines for all kinds of diseases and ailments.

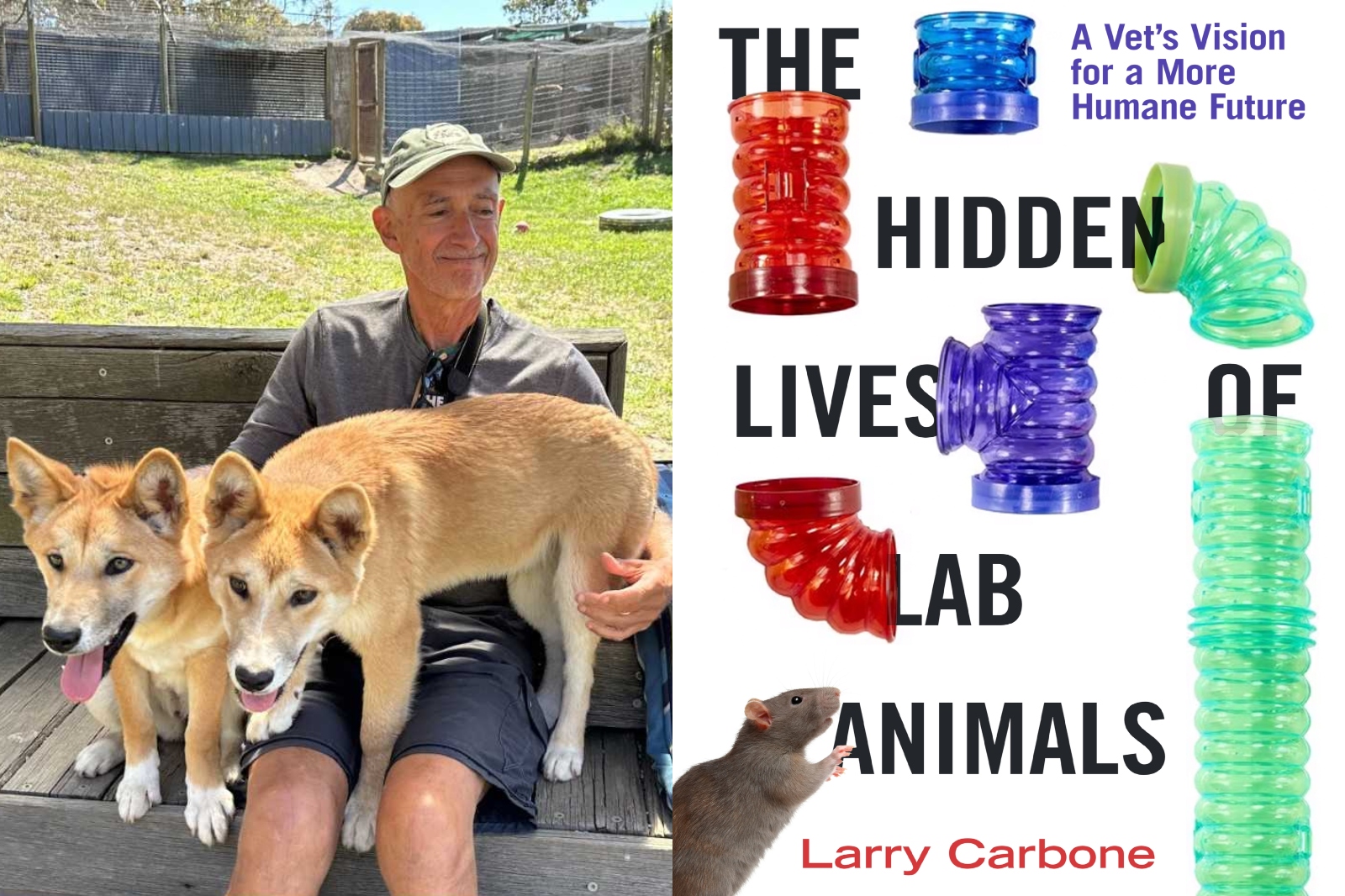

Our guest, Larry Carbone, spent decades working as a veterinarian in animal labs, including the last 26 years at UCSF. His new book tries to find a balance that respects the scientists whose work can lead to discoveries that help millions of people, while also caring about the lab animals—many of which will suffer no matter how ethically they’re treated.

His new book, out this week, is titled The Hidden Lives of Lab Animals: A Vet’s Vision for a More Humane Future. Larry Carbone, welcome to Forum.

Larry Carbone: Hey, thanks very much, Scott. Thanks for having me.

Scott Shafer: Let me begin by asking you this. As you know better than most, the treatment of animals in labs can be a very hot-button topic. There are people on all sides who have very strong feelings about the research, how the animals are protected from undue suffering, and so on. So let me start by having you describe where you’re coming from in writing this book.

Larry Carbone: Okay. Well, sure. As a veterinarian, instead of working in a private practice where clients would bring me their dogs or cats as my patients, my clients for the last decades have been scientists, and my patients have been the animals they use in their laboratories.

So I work as a veterinarian, but I also do some welfare oversight and training—teaching researchers how to take better care of their animals. And it’s an extremely polarized field, the idea of using animals in laboratories. You can hear things at both extremes, but voices from the middle—from people who are actually working in laboratories or working on these issues and trying to find some common ground that allows medical progress to continue without riding roughshod over animals—are harder to find.

So who better than a veterinarian to try to give an animal-focused view for a general audience who’ve never been in an animal lab and don’t ever want to be in an animal lab? How do we use animals? Why do we use animals? How can we take better care of them? So this is my offering to people who care about animals in laboratories.

Scott Shafer: Yeah. And you’re right that there is very little transparency in what happens inside animal labs, and that institutions, in fact, try hard to keep out undercover activists to protect the researchers. Can you say more about that and the calculation you make?

Larry Carbone: Yeah. I really do try to be, in my field, a voice for transparency—hence this book. But yes, it’s really difficult to know, even in your neighborhood, whether local colleges, universities, or companies have animals in laboratories. Can I know more? Often the answer is, well, no, you can’t—especially if it’s a private company or a private university. Trying to get information is not easy.

There are moves in Europe, in particular, to really make things more open, but it’s still hard. Part of my job when I was at UCSF, for a while at least, included fielding requests from journalists and others: “We want to look at your records. We want to see your animals.” I was one of the people whose job was to filter who got to come into the lab and see the animals.

Scott Shafer: What was your concern about letting people in?

Larry Carbone: Well, the big concern for any institution that does animal research is that people are looking for dirt. They’re looking for something they can use as an exposé to shine a negative light on what you’re trying to do in your animal labs.

There are secondary concerns, like if we have people tromping through, it’s going to stress the animals—but we can figure out ways to deal with that. The big concern is: who wants to see what’s going on in an animal lab except from a watchdog, potentially hostile point of view? So to protect the scientists and the institution, the flow of information—and certainly allowing visitors—is seriously limited.

Scott Shafer: Is it fair to say that even in the best-run animal labs, if you’re looking for dirt, as you say, you’re going to find it? Because people make mistakes, or the standards aren’t high enough depending on where you are—that kind of thing?

Larry Carbone: Well, yes. People make mistakes, and there should be ways of catching those mistakes and fixing them before animals suffer. I write a lot in my book about the fact that I don’t think our standards are high enough, where those are set mostly at the federal level.

There are very few institutions that are going to go very far beyond those standards because it costs money or could slow the science, and your researchers get upset: “Why do I have to do this extra work here? If I went to this other university across the country, I’d have more freedom to do what I want.”

But yeah—I visited, a few years back, a lab I thought was really well run. I would talk about this, but it was a private lab, and they had me sign a nondisclosure agreement before they even let me through the door. So I can’t even call out a lab that I thought was really well run and should be a role model for other labs doing similar experiments, because people are so nervous about casting too much of a spotlight on their animals.

Scott Shafer: Yeah. Well, in fact, I think you were hired by UCSF around the time that there was a lot of concern and criticism about the way—particularly primates, I think—were treated there. Now correct me if any of that is wrong. But what were you hired by UCSF to do?

Larry Carbone: Yeah. First, I was hired part time to be a staff veterinarian taking care of the animals. One of the stories I tell in my book is about treating a little marmoset monkey who was in experiments for multiple sclerosis research.

Then they asked me to set up a training and compliance program. I had a team that would go around to UCSF’s animal labs and audit how folks were taking care of the animals, and complement that by doing training—starting from the most basic: Do you understand the rules and regulations you’re supposed to follow? Do you know how to pick up a mouse without hurting the mouse, without getting bitten? So that was my job for a few years.

And yeah, during that time, the USDA—which enforces the Animal Welfare Act and sends inspectors to campuses—had been citing UCSF for problems in monkey labs and sheep labs, to the point that even the San Francisco Board of Supervisors was getting to the point of saying, “We’re going to take some control over what you do at UCSF because we don’t like this.”

Scott Shafer: That idea of politicians taking charge must strike fear in the hearts of researchers.

Larry Carbone: Yeah. Nobody liked it. There was a little bit of, “Oh, we’re UCSF. We have federal funding. We’re a state institution. What can your Board of Supervisors do?” But also, “Why don’t we not antagonize them?”

I even went to meet with Matt Gonzalez when he was head of the Board of Supervisors and tried to explain: this is the position I was hired into, this is the work we’re trying to do. We’ll still be having our USDA inspections once or twice a year as evidence that we are taking this seriously and getting things under control.

We also worked on getting the institution accredited. UCSF was the last of the UC campuses—the biggest animal users—but the last to get accredited through a private accreditation program that costs a lot of money to enroll in and get your facilities up to standards. So we did all that in the early 2000s to try to get ourselves right with the law, the regulations, and the standards of the day.

Scott Shafer: Yeah. I want to talk more about some of the research and experience you’ve drawn on in the book. But your very first job working with animals, you write, was when you were 14, working at the Boston Zoo. From what you describe, it was not a very glamorous job. Tell us about it and how you ended up there as a young teenager.

Larry Carbone: Well, the zoo at the time—Franklin Park Zoo in Boston—was just one of the worst major city zoos in the country. So they were pretty open to taking in volunteers and letting volunteers handle animals. After a few years volunteering there, I was even taking home baby tigers for nighttime feedings. It was such a fun job.

But I open the book by talking about one of my first days on the job—my fascination watching one of our big pythons kill and swallow live rats. We watched this like it was an adventure movie: “Watch out, watch out—you’re standing on the snake’s rat! What’s going to happen?”

I was fascinated with animals, but it took a while to mature enough—and I had really good mentors at the zoo—to realize those rats have their lives too. This is not on their planner for the day, to be in a snake cage. So I gradually learned to care about those animals that are so reviled.

Then I took the next step: going to vet school and getting the education so that emotional caring and ethical commitment could be layered with expertise. How do I know a rat is in fear? How do I know if a rat is in pain? What tools might I have up my sleeve as a vet to try to make their lot in life less unpleasant?

So it’s this evolution in my life of really trying to bring the best expertise I can to animal care, along with an ethical commitment that we need to give animals the best possible care—even if they’re going to be on experiments.

Scott Shafer: Yeah. We’re coming up on a quick break, but were you surprised at how much you cared about the mice and the rats?

Larry Carbone: Yeah. Yeah.

Scott Shafer: We can talk more about that after the break—about that evolution and some of your favorite animals.

We’re going to take a quick break right now. And when we come back, more with veterinarian Larry Carbone. His new book out this week is titled The Hidden Lives of Lab Animals: A Vet’s Vision for a More Humane Future.