This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal.

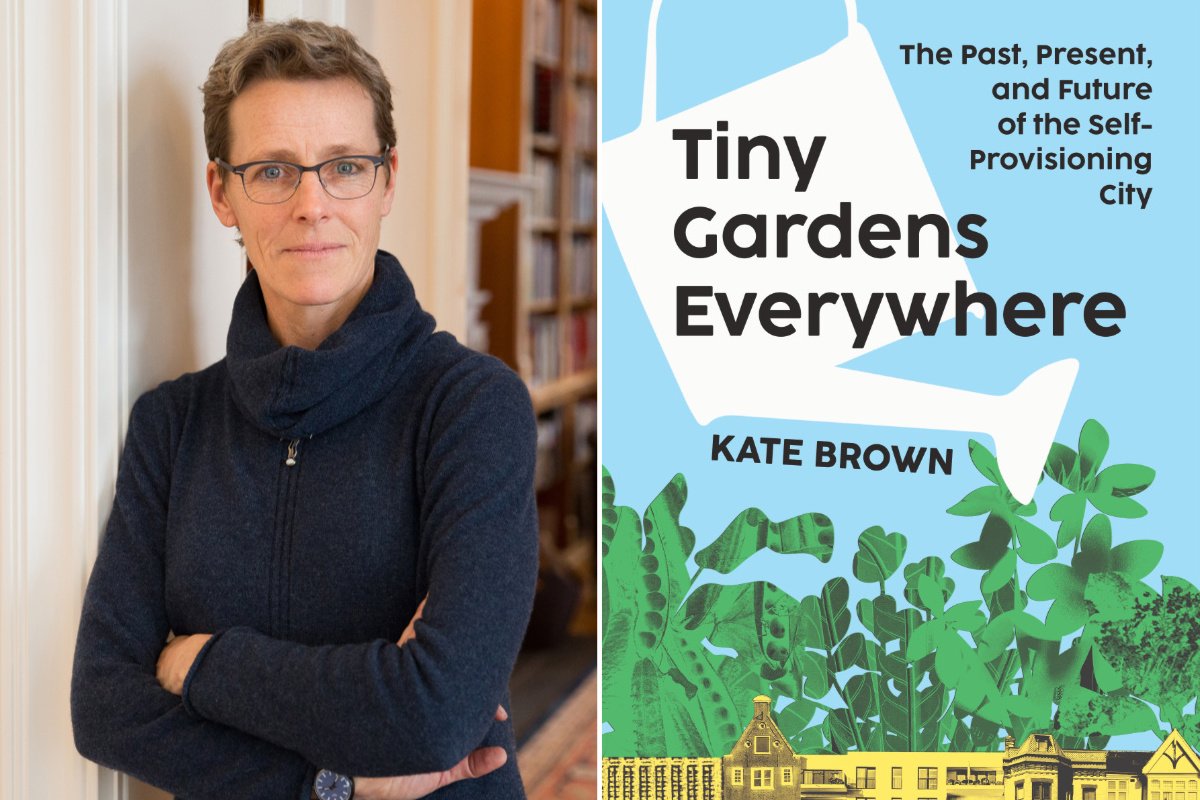

MIT environmental historian Kate Brown’s new book, Tiny Gardens Everywhere, is a surprising tour through the history and current practice of urban gardening. By looking beyond established narratives about what’s important in agriculture, she finds a hidden working-class history of food production around the home and in community allotment gardens.

These stories suggest not just an alternative food system, but something larger: a roughly democratic, high-freedom, almost anarchic kind of system that people in very different societies have discovered again and again when times got—or stayed—tough. That is to say, Brown’s research is into hyperlocal food systems, but the implications of her work are as much about the governance of societies as they are about the best ways to produce fruits and vegetables.

And she joins us here this morning. Welcome, Kate.

Kate Brown: Hi, Alexis. Thanks for having me on your show.

Alexis Madrigal: So good. Thanks for joining us. This really is a bottom-up history of urban gardening, both in terms of socioeconomic status—thinking about the ways that working people are gardening—and also looking at agriculture kind of from the soil up, in particular. When did you first get interested in the intersection of those two things?

Kate Brown: Oh, that’s a great question. You know, it was 2020, and we’re all home—it’s COVID. A friend of mine and I were both gardeners, and we thought, well, you know, this school across the street—I was in Washington, DC at the time—is mothballed, and there’s nobody around. So why don’t we just slip in some fig trees and pawpaw and persimmon, maybe some raspberries and thornless blackberries in the understory, and some strawberries on the ground?

We had a little bit of permission from the school gardener. This is a school where Michelle Obama had started her school garden campaign, and it’s in the Mount Pleasant neighborhood of DC. And we just started planting.

I already knew how much food a person could grow on something about the size of two dining room tables. We fed my small family of three with that produce. And we made this kind of food forest around the school. That’s what got me thinking about the power—both of how much food you can grow in urban areas that are rich with organic nutrients, but also how much community comes out of the woodwork when you’re sitting outside and there are figs popping out and strawberries on the ground, and kids are delighted.

Alexis Madrigal: This history is a little different from what we might think of as an urban farm—maybe a couple of acres inside a city, with a few people who tend it or work there. You’re really thinking about a different style of garden. And you started out looking at this in England.

Kate Brown: Yeah. Well, you know—when do cities get big? The 1850s. London goes from being a million to three million people, Berlin explodes, Chicago had almost no people and suddenly there are like 1.7 million. So it’s just at this time that rural people are being pushed out of their villages.

In those villages, they almost universally didn’t really have a concept of private property so much as they had a concept of communally owned property. In an English village, the villagers would all have fields that they farmed in common. They’d decide together: we’re going to have rye here and wheat there and potatoes over there, and then they would go out and work them together.

They would also have pasture they managed collectively, moving their sheep down the fields so it was lightly grazed and manured well, getting ready for the next crop. And then they had this idea of common right—common law right—which was the right to food, fuel, and shelter. So you had the right to go into the forest and get sticks and branches for fuel, to collect mushrooms and nuts and berries. Every hedgerow wasn’t filled with thorns—that came later when landowners wanted to keep people out. They were living pantries of fruits and berries and nuts, with herbaceous plants on the bottom.

So people got used to the idea that you could take the wastes and the commons, and from that derive most of your subsistence.

Now this was a problem for the landowning class in England, who in the 19th century—really beginning around the early 1800s—decided they were interested in farming themselves. They had always just collected rents. But now they thought, we could do this. And for that, they weren’t going to do the work themselves—they wanted labor.

But these self-subsisting peasants weren’t that interested in doing too much work. You might ask, “Can you come thresh my wheat?” and they’d say, “No, I’m going off to a cricket match,” or whatever. That was infuriating—that workers weren’t responsive. And so enclosure occurs: make sure people can’t grow their own food, and then they need wage labor just to feed themselves and put a roof over their heads.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. It’s so interesting because I’ve read about the Enclosure Acts—famous in political science as a moment in global history. And then we have this echo when people use the phrase “the tragedy of the commons.” But what’s really interesting is that a lot of thinking about this hasn’t contended with the fact that the commons actually worked pretty well. At least in the telling in this book, this was a productive, high-yield agricultural system that allowed people to provision for themselves without needing wage labor. That’s not exactly the story of the tragedy of the commons that an economist wants to tell.

Kate Brown: No. In fact, even Jethro Tull—not the band, but Jethro Tull, the guy who invented early agricultural machinery, including the seed drill and the harrow—even he said my mechanized agriculture is not as productive per acre as the peasants’. But it’s cheaper for me, because I don’t have to pay so much for seeds, and I don’t have to pay labor costs for workers to sow seeds and hoe rows by hand.

So just like industrial agriculture today, it’s not that productive per acre, but it works well with machinery. It cuts down on labor, makes some people a lot of money, while other people go hungry. And that’s what happened. Hungry people were pushed out of their villages, the commons were closed.

The commons, as you say, Alexis, worked really well because they were ruled by people who agreed—it wasn’t a free-for-all. Everyone wasn’t taking whatever they wanted. That’s what the landowners were doing. Instead, people carefully grazed, stopped grazing, avoided overgrazing—all of that.

So they end up in the cities as the famous landless proletariat, with nothing to sell but their labor for eight, ten, twelve, sixteen hours a day. And then the narrative shifts. People who were in favor of enclosure say, well, wait a minute—now we have all these paupers going up and down the roads begging for work, and the children look Dickensian and miserable. What are we going to do?

So they come up with this idea of allotment gardens, invented both in rural areas and outside cities in England.

Alexis Madrigal: This is just where they allow people to create some land they can work?

Kate Brown: Yeah. So, you know, 2,000 acres are enclosed, and they give 20 acres to the community to grow some subsistence vegetables. But they would calculate: how small should we make it? We need it small enough so they can’t feed themselves completely, so they still need to work for us.

And I think that tells you enclosure was less about improved agriculture or efficiency. It was really about gaining control of labor.

Alexis Madrigal: So interesting. In the U.S., where do we see this sort of thing popping up? Obviously, we have a very different history. The commons here were actually Native American land—there’s a really different context. So where do you first see this present in the U.S.?

Kate Brown: Well, I didn’t go back to the colonial period, where there were these tensions between Indigenous land uses and settler colonial land uses. Where I really focused was Washington, DC, in the 1910s.

Like most American cities, Washington had been an integrated city until racial covenants and zoning ordinances started to separate populations by race. In DC, there was a persistent attempt to move African Americans out of the central parts of the city—around the White House and the Capitol—and across the Anacostia River, “east of the river,” to a triangle of land where Black residents could buy land that had once been farmland. They could buy tenth-of-an-acre lots.

Meanwhile, people were also moving up during the Great Migration, coming from rural areas in the South, and they too settled east of the river. What we found is that they often purchased not just one lot, but between two and six. One family had six lots. They put a tiny house in the middle, usually built themselves, and then all around it they started gardening.

They brought with them from the South grandma’s peach tree, seeds from favorite bean plants—that kind of thing. Not the crops that oppressed them. No cotton, no sugar. But the foods that had nourished the family. And they started growing those foods.

This was a part of town with no infrastructure. The people who ran DC by fiat at the time were congressmen—often Dixie Democrats—so there were no sewers, no running water, no garbage collection, no paved surfaces until the 1950s in this neighborhood. But that was kind of okay. These were ways people made the best of structural racism.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah.

Kate Brown: And I’ll tell you more after the break.

Alexis Madrigal: We’re talking about the history of urban gardening with Kate Brown, professor of the history of science at MIT and author of the book Tiny Gardens Everywhere: The Past, Present, and Future of the Self-Provisioning City.