This partial transcript was computer-generated. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Alexis Madrigal: Welcome to Forum. I’m Alexis Madrigal. Perspective is everything, no? Where you are in a system allows you to see certain things that other people might not from where they’re sitting. Public defenders are uniquely positioned to see the day-to-day mechanics of the justice system. They’re sort of internal opponents of much of the rest of the institution, and so they’re both intimately familiar with how police officers, district attorneys, and judges act—and they’re often at odds with them.

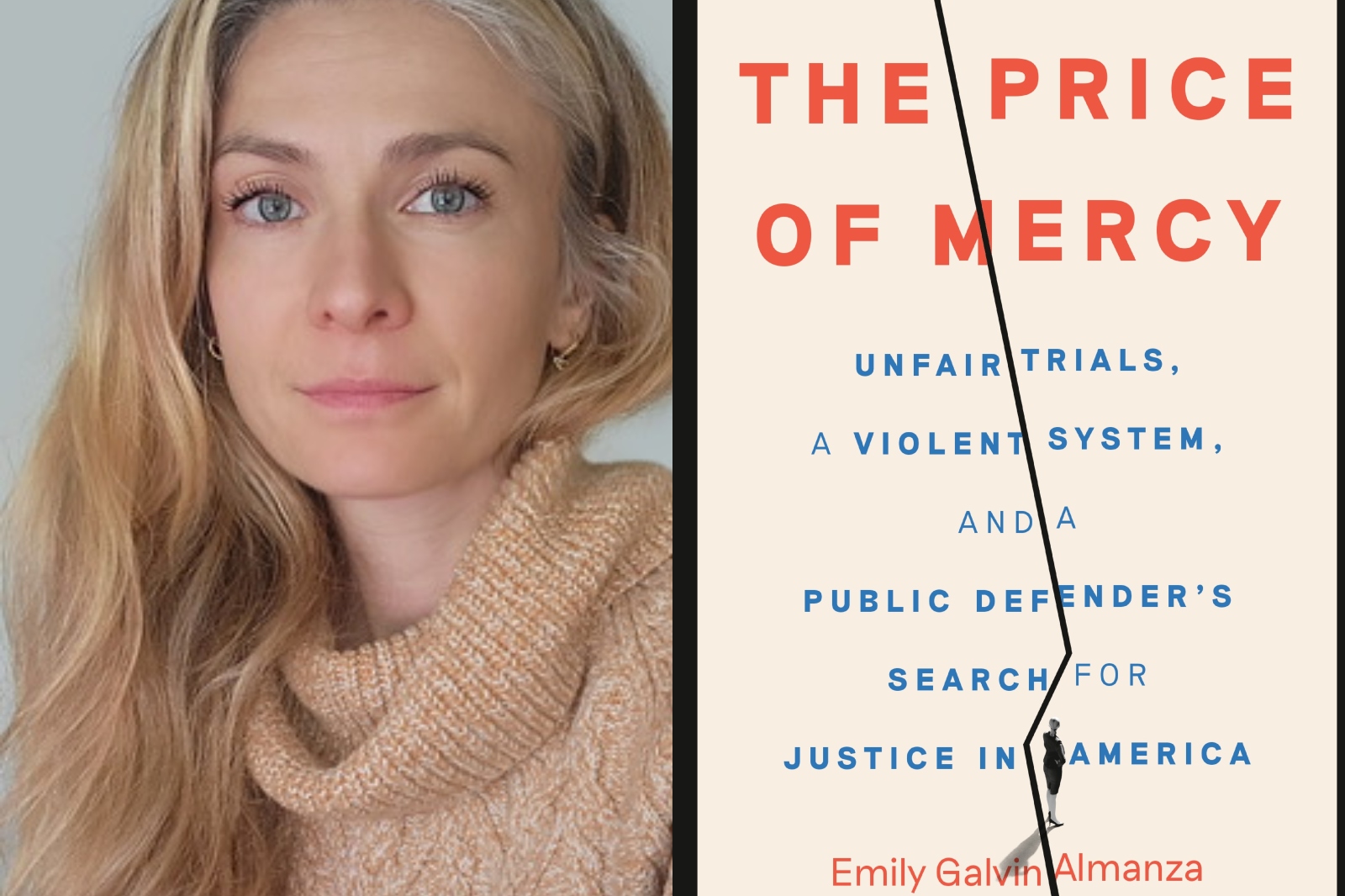

It’s a fascinating lens for a book on a system that, for many of us, has been shaped more by television than by real knowledge. So if you want one volume on all the many, many things wrong with how the criminal legal system actually works, The Price of Mercy: Unfair Trials, a Violent System, and a Public Defender’s Search for Justice in America is your book. Its author, Emily Galvin-Almanza, joins us today. She’s the co-founder and executive director of Partners for Justice, which supports and empowers public defenders. Welcome.

Emily Galvin-Almanza: Thank you so much for having me.

Alexis Madrigal: So let’s talk a little bit—I mean, this book is an indictment of the whole damn system, you know? And there are all these ways to fix it. We’re going to talk about those problems. But let’s start with some of the terminology. You call this the “criminal legal system” in the book. Why do you call it that instead of “criminal justice”?

Emily Galvin-Almanza: The book is a public defender’s search for justice in America. I’m still looking, man. Look—I call it the criminal legal system because I try to be very careful with my language. This system is full of what I think of as linguistic anesthesia, where we use words that dehumanize some people—like “criminal,” “felon,” “con,” “ex-con,” “alien.” And we use other words that erase harm. Like, we’re not putting a new mother in a fetid, cold cell; we are sentencing the offender to custody. And we use words like “custody” that otherwise imply an embrace or caregiving.

So I try to pick words that are as accurate as possible. It is a legal system. It is a court system. Is it a justice system? I think a lot of people would push back on that.

Alexis Madrigal: So let’s talk about your work when you were in the courtroom. You worked both here in San Jose, but also with a legendary group in the Bronx as a public defender.

Emily Galvin-Almanza: I mean, I think the public defender’s office here is also pretty legendary. I’ve got to give a shout-out to LA County—also pretty legendary. I worked there as a student. But yeah, I started out in California government public defense, working for county agencies. And I wanted to find out what this holistic defense thing was all about.

So I left California. My husband and I were actually both public defenders, and we took jobs at the Bronx Defenders. And it was amazing. It was wonderful to work at an office that—well, for those of you who don’t know what holistic defense is—

Alexis Madrigal: What is it?

Emily Galvin-Almanza: Yeah. It involves bringing into one agency people from many different disciplines who can work on the many different problems that face our clients. Because when a person comes into the criminal court system, there are often a lot of things driving them there—underlying problems. And there’s also a lot that arises from their involvement. Just being arrested can cost you your housing, your job, access to your kids, medications, your health care benefits. There’s so much that can go wrong.

So what holistic defense does is put under one roof criminal defense attorneys, but also family defense attorneys, immigration attorneys, housing attorneys, and social workers of all kinds, along with client advocates—which is what I later focused on extensively. It tries to ensure that when our clients receive representation, that representation isn’t limited to the criminal defense case. They’re able to get more kinds of lawyers and social workers for more of what they actually need, the result being better outcomes.

Alexis Madrigal: Yeah. How much better are the outcomes?

Emily Galvin-Almanza: Well, I’ll talk about Partners for Justice’s outcomes, because holistic defense’s outcomes have been fabulously studied. There was a great study by Paul Heaton on the Bronx Defenders. Initial research on holistic defense shows better outcomes—more dismissals, more people not confined pretrial, more people coming home with no negative impact to public safety.

That’s really crucial, because I think a lot of people imagine that if you let all these people out and get more cases dismissed, crime will be rampant. But no—the study showed no subsequent increase in crime or arrests.

While I was working in the Bronx, I couldn’t stop thinking about Santa Clara County. I was like, it’s great that people in the Bronx have this, but why can’t Santa Clara have it? Why can’t LA have it? Why can’t any defender who wants to do this have these resources?

So I stepped back from trial work to start Partners for Justice, to bring this kind of root-cause thinking and wraparound care to everyone. We did it by placing what we call client advocates—sort of non-attorney superheroes. They’re interdisciplinary service specialists who can work on housing or employment.

Alexis Madrigal: Sort of a caseworker.

Emily Galvin-Almanza: Sort of a caseworker, but also a great storyteller. They can do what’s called mitigation in court—telling a person’s story in a way that contextualizes their conduct and asks for a better outcome.

We started embedding these client advocates with public defenders all over the country. Now, eight years in, this work has eliminated almost 9,000 years of potential incarceration that never came about. And we just did a study with the University of Pennsylvania showing that having this team can increase non-convictions—dismissals and diversion—by nearly 50 percent.

Alexis Madrigal: Let’s talk a little bit about the history of the public defender’s office. Where did the idea come from? Have we had public defenders throughout our history? It’s fairly recent.

Emily Galvin-Almanza: Okay, this is something I really like to geek out on, so you’re going to have to rein me in. We often credit the invention of public defense to the Supreme Court’s decision in Gideon v. Wainwright in the 1960s. That’s when the Court decided that if a person is accused of a crime, they have the right to an attorney even if they can’t afford one, and the government must provide that service.

But that’s not when the idea was invented. We go back to the 1890s, to a woman named Clara Shortridge Foltz. She was from Iowa, like me—but unlike me, she ran away from home as a teenager with a Union soldier, had five kids, and he left her high and dry in San Jose, California. Everything comes back to San Jose.

She supported herself any way she could. She was a suffragette and involved in movement work. She started working for a judge and thought, “I could do this. I could be a lawyer.” But the law didn’t allow her to be one. So she wrote a bill that changed California law from saying “any white man” could be a lawyer to saying “any person” could be a lawyer. The bill passed the legislature, but the governor wasn’t going to sign it.

Guess who showed up in his office? Clara Shortridge Foltz. She pulled it out of the discard pile and slammed it down on his desk—this is how I imagine it.

Alexis Madrigal: Cinematic.

Emily Galvin-Almanza: She did pull it out of the discard pile—that part we know. She got the governor to sign it and became an attorney. But if you’re in the 1890s and you can afford a lawyer, are you going to hire a single mom with five kids? Probably not. So she took on public cases, worked as a prosecutor for a time, and did defense work. She became deeply passionate about this issue.

In 1893, she gave a speech at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. You can find it on speakingwhilefemale.co—it’s a barnburner. She describes police corruption, prosecutorial overreach, and the prioritization of winning over justice—problems we still see today. In that speech, she argued that if the government takes on the duty of prosecuting civilians, it must also take on the duty of defending them.

Clara Shortridge Foltz was the first person to meaningfully call for a public defender in this country. And shortly after, in 1913, the Los Angeles County Public Defender opened its doors—the first public defender’s office in America.

Alexis Madrigal: That’s fascinating. What makes the public defender so interesting to me is that the rest of the criminal legal system—the police, the district attorney, all these factions—seem to be driving toward prosecution. Even though the system is supposed to operate on a presumption of innocence, that’s not really the mindset prosecutors approach cases with.

What do public defenders see and know that people who aren’t at the courthouse every day might miss?

Emily Galvin-Almanza: All the things. That’s why I wrote the book.

Alexis Madrigal: It’s great. The Price of Mercy—coming in hot.

Emily Galvin-Almanza: One thing that’s really important to recognize is that the public mostly hears from police and prosecutors. They have communications departments. They’re used to shaping public narratives. Police unions are notorious for aggressively targeted messaging to achieve policy goals, and prosecutors do it too. They’re elected officials, used to campaigning.

So through media, through shows—everything Dick Wolf has ever done—the public absorbs the prosecution’s perspective. But that’s just one perspective.

Defenders have a much harder time speaking out because it’s often not in our clients’ best interests. If you’re accused of something, you may want to resolve it and move on with your life without being on the front page of the paper. So we’re rarely in front of a gaggle of cameras.

But the problem is, we should be, because the system makes false promises. It says there’s a presumption of innocence, but we have to fight to make juries actually apply it. It says you have a right to a jury trial, but 90 percent of cases end in guilty pleas. People assume that’s because most defendants are guilty, but really it’s because the pretrial process is so grinding and harmful that people are pressured into pleading guilty.

Every day, public defenders stand next to people during plea colloquies. The judge asks, “Are you doing this freely and voluntarily? Did anyone force you to make this decision?” And the honest answer is yes. This person had to come to court seventy times, take time off work, and now their boss is threatening to fire them. Or they’re sitting in Rikers Island and the prosecutor says, “Take this plea and you can go home.” Public defenders know the truth.

Alexis Madrigal: We’ve been talking with Emily Galvin-Almanza, author of The Price of Mercy: Unfair Trials, a Violent System, and a Public Defender’s Search for Justice in America. We’ll be back with more right after the break.